Access, Waiting Times and Expenditure on Healthcare

Ireland remains the only western European country without universal coverage for primary care[1]. Ireland’s health system ranked 22nd out of 35 countries in 2018 but on the issue of accessibility, Ireland ranked worst[2]. That report notes that even if a waiting-list target of 18 months were reached, it would still be the worst waiting time situation in Europe. Quality of health care is considered generally good by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, but access to services is constrained by costs and waiting times.

Access, Waiting Times and Expenditure on Healthcare

Irish hospitals are working at near full capacity. The number of hospital beds in 2019 (2.9 per 1,000 population) was the third lowest in the EU[3]. Pre-COVID-19, hospitals frequently ran at 95 per cent occupancy rates – above the capacity considered safe[4]. A high utilisation rate of hospital beds can be a sign of hospital efficiency, but it can also mean that too many patients are treated at secondary care level[5].

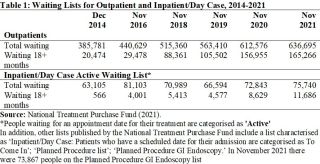

Ireland’s complex two-tier system for access to public hospital care means that private patients have speedier access to diagnostics and treatment, while those in the public system can spend lengthy periods waiting for first appointments with specialists and for treatment. Official statistics suggest that an enormous 636,695 people were waiting for an outpatient appointment in November 2021 while 75,740 people were waiting for treatment as an in-patient or day case[6] . Among them, those waiting 18+ months for an outpatient appointment were signification at 165,266 people while 11,686 people were waiting 18+ months for an inpatient/day case appointment. The COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to the numbers on the waiting lists in recent times. However, as Table 1 shows, the numbers were particularly high in November 2021, but there have been very high numbers on waiting lists over many years.

Accessing our complex system depends on whether one has a medical card, a GP visit card, private health insurance, private resources to spend on health services, where one lives and what type of services one is trying to access; it is people who are poorest, sickest and those with disabilities who find it hardest to pay charges, to negotiate access, and who must wait longer for care[7]. As well as undermining equity and efficiency in the health system, private health insurance represents a financial burden on households, accounting for around 3 per cent of household spending on average in 2015–2016, up from 2 per cent in 2009–2010[8]. Furthermore, while 46 per cent of the population has private health insurance, about 20 per cent has neither private health insurance nor a medical card[9]. The medical card system protects many households from financial hardship, but poorer households are still disproportionately likely to experience financial hardship, and protection has been eroded over time[10]. Even relatively low user-charges can operate as barriers to access and lead to financial hardship for very poor households, and there is a high degree of income inequality in unmet need for prescribed medicines in Ireland, with disparities between the richest and poorest being particularly large relative to dental care. The European Health Interview Survey (EHIS) shows that unmet need for prescribed medicines in Ireland is on average more than twice as high as the EU average and more than twice as high among people with the least education than those with the most[11]. The pandemic also limited access to care for people with health conditions not related to COVID-19 and unmet needs for medical care because of delayed or missed consultations are likely to lead to poorer health outcomes in the future.

Eurostat publishes self-reports of unmet needs for medical care. When we look at reasons associated with problems of access (could not afford to, waiting list, too far to travel) in Ireland the rate was 2.1 per cent (for those aged 16+ in 2020) (Eurostat online database hlth_silc-08). However, low-income groups are most affected: 4 per cent in the lowest income quartile, contrasting with 0.4 per cent in the highest) (again for those aged 16+ in 2020). When considering other survey instruments such as the EHIS (carried out approximately every five years), Ireland had the second highest rate of unmet needs for medical care due to cost, waiting times or travel distance among EU countries in 2014, at 40.6 per cent, substantially higher than the EU as a whole (26.5 per cent)[12]. These differences may be explained by differences in the methodologies used by each instrument.

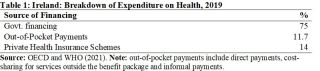

Total health care spending as a percentage of Irish Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was 6.9 per cent in 2018 (the latest year for which comparable data are available from the Central Statistics Office[13], putting Ireland fifteenth in EU-27 for total health spending. However, as a percentage of Modified Gross National Income (GNI*[14]), total health expenditure in Ireland was 11.4 per cent in 2018 – the second highest amongst EU countries after Germany[15]. Growth in public spending on health since 2014 has been driven by acute hospitals, increased staff numbers and growth in medicine costs[16]. While cross-country comparison of healthcare expenditure is challenging, analysis suggests that Ireland’s apparent high ranking in an international context is driven by relatively high prices for healthcare delivery, particularly salaries, rather than due to the volume of care delivered. International comparison suggests that spending on inpatient care and long-term care in Ireland is relatively high[17]. An ESRI report suggests that certain care currently delivered in hospitals could, in line with current Sláintecare proposals, be more appropriately delivered in the community if there were increased investment in community care[18].

Government financing accounted for 75 per cent of total health expenditure in 2019 compared to the EU average (80 per cent) [19]. While the proportion of expenditure from private health insurance schemes was 14 per cent (the second highest in the EU and almost three times higher than the EU average) almost half of the Irish population has in-patient health insurance[20].

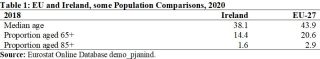

Another issue is that healthcare costs tend to be higher in countries that have larger populations of older people, and Ireland currently has a relatively low proportion of older people though it is growing rapidly, as already discussed. People aged 65+ in Ireland make up 14.4 per cent of the population (2020) while the EU average is 20.6 per cent. See Table 3.

Before the onset of COVID-19, the Irish public hospital system was operating under pressure from population growth and ageing, and as a result of cuts to bed capacity in the preceding decades[21]. According to the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, the pandemic exposed health system weaknesses – in particular a shortage of health workers in the public sector and low intensive care unit capacity in public hospitals and it also revealed some strengths in responding to crises, including the ability to develop technological solutions and to mobilise additional funding rapidly for health reform, health workforce and hospital resources[22].

Like the governments of other countries, the Irish government made additional allocations to the health sector to deal with the pandemic. These commitments included expanding hospital capacity, developing primary and community-based responses, procurement of medical equipment, and an assistance scheme for private nursing homes. The successful delivery of the Covid-19 vaccination programme illustrates the ability of that system to respond in a coordinated way, adapt as challenges emerge and successfully implement a complex programme countrywide. As of the end of August 2021, Ireland’s vaccination programme had achieved better rates than the EU average, with almost 70 per cent of the population receiving two doses (or equivalent) and with COVID-19 accounting for 5,100 deaths, a death rate about one third lower than the EU average[23].

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted how our healthcare services, which had struggled in normal times, had to be provided with significant additional resources in amounts that would not even have been considered previously. What had been claimed to be impossible was taken to be the only sensible course of action during the crisis. As the scale of the pandemic’s impact on the health system recedes, the period ahead is one where there is a unique opportunity to implement significant reform of Ireland’s healthcare system. It is important to ensure that the approximately €4bn additional resources committed for the development of the healthcare system in 2021 are retained and now fully rolled out in 2022 to implement Sláintecare.

Policy Priorities

Social Justice Ireland welcomed the recognition within Sláintecare that Ireland’s health system should be built on foundations of primary care and social care. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted shortcomings in our healthcare system across a range of areas and also demonstrated how vital an integrated public system of care is, with health care workers having been at the heart of the response to challenges unprecedented in living memory. We cannot return to a two-tier healthcare system and access to healthcare based on need, not income, should remain an important aim for Ireland’s healthcare system. Investment in a reconfigured model of healthcare is overdue, one that emphasises primary and social care. In the context of our past mistakes, it is important that Ireland begins to plan for this additional demand and begins to train staff and construct the needed facilities. It is also necessary for leadership that communicates the need to invest in reform now so that the necessary services are in place to enable us to afterwards shift to a different model of care that emphasises primary care more.

The following is a summary of key policy priorities and actions that Social Justice Ireland recommends:

- Ensure that announced budgetary allocations are valid, realistic and transparent and that they take existing commitments into account.

- Complete the roll-out of the Community Health Networks across the country and thus increase the availability and quality of Primary Care and Social Care services.

- Act effectively to end the current hospital waiting list crisis.

- Work towards full universal healthcare for all. Ensure new system structures are fit for purpose and publish detailed evidence of how new decisions taken will meet healthcare goals.

- Enhance the process of planning and investment so that the healthcare system can cope with the increase and diversity in population and the ageing of the population projected for the next few decades.

- Ensure that structural and systematic reform of the health system reflects key principles aimed at achieving high performance, person-centred quality of care and value for money in the health service.

[1] OECD (2019b) State of Health in the EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2019. Paris: OECD Publishing

[2] Health Consumer Powerhouse (2019). Euro Health Consumer Index 2018. Health Consumer Powerhouse.

[3] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[4] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[5] OECD/European Union (2020), Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris

[6] National Treatment Purchase Fund (2021; 2022). National Waiting List Data Inpatient / Day Case Waiting List/Outpatient Waiting List [Online] https://www.ntpf.ie/home/nwld.htm [Jan-Mar 2022]

[7] Burke, S, Normand, C., Barry, S., and Thomas, S. (2016) ‘From Universal health insurance to universal healthcare? The shifting health policy landscape in Ireland since the economic crisis.’ Health Policy. 120. 235-340

[8] Johnston B, Thomas S, Burke S.(2020) Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Ireland. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

[9] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[10] Johnston B, Thomas S, Burke S.(2020) Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Ireland. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

[11] Johnston B, Thomas S, Burke S.(2020) Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Ireland. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

[12] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[13] Central Statistics Office (CSO) (2021). Measuring Ireland’s Progress 2019 CSO, February [Online] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-mip/measuringireland…

[14] Modified GNI is an indicator recommended by the Economic Statistics Review Group designed to exclude globalisation effects that are disproportionally impacting the measurement of the size of the Irish economy.

[15] Central Statistics Office (CSO) (2021). Measuring Ireland’s Progress 2019 CSO, February [Online] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-mp/measuringirelands…

[16] Johnston B, Thomas S, Burke S.(2020) Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Ireland. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

[17] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[18] Keegan, C., Brick, A., Bergin, A., Wren, M-A., Henry, E., and Whyte, R. (2020) Projections of Expenditure for Public Hospitals In Ireland, 2018–2035, Based On The Hippocrates Model Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute

[19] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[20] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[21] Keegan, C., Brick, A., Bergin, A., Wren, M-A., Henry, E., and Whyte, R. (2020) Projections of Expenditure for Public Hospitals In Ireland, 2018–2035, Based On The Hippocrates Model Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute

[22] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.

[23] OECD and World Health Organization (2021). State of Health in The EU: Ireland Country Health Profile 2021.