Green transition – time to prepare for change

The green transition will drive a transformation of local labour markets, with new skills needed, and others becoming redundant. This shift to a sustainable and net-zero economy will result in a significant transformation of local labour markets, as workers move into different occupations and sectors. The green transition compounds megatrends such as digitalisation and demographic change that have also been reshaping the geography of jobs and the world of work. Government must begin to plan for and manage the green transition now, ensuring that the correct policies are pursued so that social divides and inequalities within and between regions are not exacerbated.

Green jobs

According to a new report from the OECD (Bridging the Green Divide) the green transition will drive a massive shift in the demand for skills, jobs, or specific goods more rapidly than the market can adjust and it could (without appropriate strategies and supports) deepen social divides within regions.

New skills will be needed throughout the economy, whether it is retraining construction workers on environmentally friendly materials and techniques, or reskilling automotive workers for electric vehicle production. The jobs and skills needed will differ geographically—some local labour markets will have people with skills that can be easily redeployed and others not.

The greening of the labour market will have several effects on people, places, and firms. New types of jobs will emerge, creating opportunities in occupations that may not yet exist. There will be the loss of some existing jobs, especially in highly polluting activities such as coal and gas extraction. The green transition will lead to a shift in the skills required for many other jobs throughout the economy.

Addressing these challenges requires a rethinking and updating of education curricula and training courses to enable workers to attain the skills demanded by the changing labour market. But because the geography of these transitions will also differ, a place-based strategy will be vital, with local economic development and business support programmes complementing national green transition policies, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises.

The risks and opportunities for workers are uneven across different places within the same country. Regions relying on high-emission sectors are more likely to see jobs disappear due to green policies. Likewise, economic opportunities and “green” job creation will not materialise equally everywhere.

The green transition has a strong gender dimension and education dimension in the labour market. Women tend to be under-represented in green-task jobs, accounting for only 28% of them, requiring policy efforts to raise female participation in the green transition. On the other hand, men will be the most affected by the disappearance of polluting jobs.

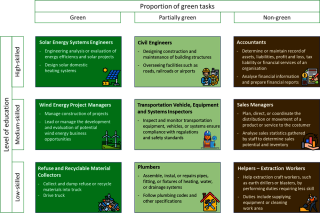

The majority of workers in green-task jobs are currently high-skilled and have completed tertiary education. In contrast, polluting jobs, at risk of disappearing, are held by individuals with lower educational attainment and in medium-skilled occupations. So far, high-skilled and educated workers have predominantly captured the employment opportunities brought about by the green transition. In contrast, people with lower educational attainment and in medium-skilled occupations are at higher risk of displacement due to the green transition.

With both the challenges and opportunities of the green transition being place-specific, local actions or national initiatives tailored to local realities are needed. Additionally, local and regional governments cover the spaces where local development needs to be joined up with employment and skills policies. Skills development and retraining are vital to ensuring that workers have the right skills to prosper in a changing world of work and are a prerequisite for making the green transition a just transition.

What are green jobs?

Definitions of green jobs vary. The United Nations defines green jobs as jobs in sectors that contribute substantially to preserving or restoring environmental quality and minimise waste creation and pollution[1]. The ILO defines green jobs as “decent jobs in any economic sector (e.g., agriculture, industry, services, administration) which contribute to preserving, restoring and enhancing environmental quality.”[2] The Irish Government has yet to define what a ‘green job’ is in the Irish context.

The OECD report defines green jobs based on the number of green tasks in particular roles, scores them based on the proportion of tasks in that role that are green.

Note: The greenness of occupations is based on their task content and whether those tasks are green or not. The greenness score of occupations ranges from 1 (all tasks are green) to 0 (all tasks are non-green). The classification of high-, medium-, and low-skilled occupations follows ISCO.

Source: OECD elaboration based on O*NET’s Green Tasks Data.

Who is employed in green jobs?

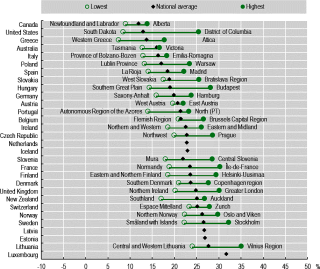

According to the report, labour markets have not, on average, become much greener over the last decade. The share of workers in green-task jobs grew from 16% in 2011 to almost 18% in 2021. However, this masks significant differences across regions, with changes ranging from an increase of 10 percentage points to a decrease of 7 percentage points. The main measure is the share of green-task jobs in a regional labour market where green-task jobs are defined as those that have a significant green component (at least 10% green tasks) and enables comparisons of differences across workers in different jobs within regional labour markets.

Regions that invest more in R&D recorded larger growth of green-task jobs. The majority of the labour force in OECD regions is employed in non-green-task jobs. Less than a fifth of the workforce in the OECD holds green-task jobs that were either created as a result of the green transition or because their task composition changed. Regions in southern Europe - in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain – as well as in North America tend to have a lower share of green-task jobs, while regions in the Baltic and Nordic countries score high on this measure.

When it comes to where green jobs are, they are overrepresented in large firms with at least 250 employees. Large firms account for around 31% of green-task jobs, but only for around 25% of other employment. In contrast, smaller firms provide relatively few green-task jobs compared to their overall share of total employment. This raises questions about the type of supports and incentives that are needed to increase green jobs in micro and small enterprises. In Ireland, the lowest level of green-task jobs is recorded in the Northern and Western region and the highest in the Eastern and Midlands region.

Source: OECD, 2023

Learning from other transitions

The effects of past and ongoing labour market transitions bear similarities to the green transition. Digitalisation, globalisation and the exit from coal have been disruptive to local labour markets and communities and have had an uneven impact on regions. The economic readjustment and diversification that occurred in negatively impacted regions had varying success. Good practises and success drivers in these regions can serve as lessons for the hardest-hit regions in the green transition.

According to the OECD, past transitions have been largely market-driven, whereas the green transition is largely policy driven. This gives policy makers more opportunities to control both the supply and demand effects of labour markets but it also comes with great responsibility in terms of getting policy right.

Drivers of successful local policy in past transitions:

- Share a clear and long-term vision and strategy for local economic transition.

- Invest in local re-skilling and re-education programmes..

- Build strong coalitions focussing on social inclusion.

- Invest in the attractiveness of the region and promote innovation..

- Assist laid-off personnel quickly immediately after—or ideally before—they are let go.

- Use regional comparative advantages.

National and local governments need to step up efforts to ensure that local skills systems are ready to enable a green transition and deliver it in a socially just way. The OECD report outlines some key policies in this regard.

- Skills and labour market policies need to keep up and be well-aligned with environmental regulations. So far, environmental policies, which drive the demand for green skills, have typically been developed in isolation from skills and labour market policies, which drive the supply of skills. This needs to change (i) to help ensure that workers who are negatively affected by the green transition are not left behind, and (ii) to avoid green skills shortages that could hinder the achievement of climate goals. Alignment of these policy areas requires close collaboration between the responsible ministries.

- Local and national governments need to develop a forward-looking and comprehensive adult learning strategy to help workers acquire skills required in a green economy. That includes a systematic review of educational curricula to reflect the shift in skills demand, driven by the green transition. In addition, tailored training offers may be needed in sectors and regions most affected by the green transition – both those that face displacement of a significant share of workers, and those that are at the forefront of the green transition. Given that a high share of adult learning happens at the workplace, policy makers should also support and incentivise employers to up-skill and re-skill staff.

- Public Employment Services (PES) have an important role to play by supporting vulnerable groups to support a just green transition. Workers in polluting jobs, who tend to have lower educational attainment and hold medium-skilled occupations, will be the most negatively affected by the green transition. Supporting these workers early on through a tailored mix of career guidance, training, and income support maximises chances of re-employment and helps to reduce social resentment. At the same time, it is important that the services offered by PES overall reflect the impact of the green transition. Without that, unemployed individuals are less likely to benefit from the employment opportunities brought on by the green transition.

- Local skills systems can only be effective if they are based on timely labour market intelligence that is aligned with policy use. To achieve that, assessments of skills needs would ideally (i) reflect the impact of environmental regulation on skills demand, (ii) be available at a sufficient level of sectoral and regional disaggregation, and (iii) be developed with data users. In regions with a high share of polluting jobs, additional analysis of the characteristics and skills of workers at risk of displacement may be needed.

- The impact of the green transition will differ across regions, which amplifies the role of local governments and stakeholders. Engagement of regional and local governments can help officials design policies tailored to local needs. Local governments are also well-placed to act as initiators of local skills coalitions that improve the design and delivery of local policies and secure public buy-in for the green transition.

Establishing strong links between vocational education and employers can help ensure training meets demand in the local labour market. Apprenticeships can serve as a mechanism to address green labour market shortages, by helping participants develop the right skills that are directly employable.

Social Justice Ireland view

Government must begin to plan for and manage the green transition now, ensuring that the correct policies are pursued so that social divides and inequalities are not exacerbated. Regional dialogue and engagement to support place-based strategies are key to supporting communities during the transition, as risks and impact will vary across regions within the same country. There is a risk of polarisation and inequality in the labour force if effective upskilling and reskilling systems are not put in place in a timely fashion. A place-based strategy, aligned with Our Rural Future should be developed, with a particular focus on supporting micro, small and medium enterprises and resourcing and developing local skills systems. Learnings from past transitions both in Ireland (Bord na Mona closure in the Midlands) and further afield regarding what policies work best must be applied to the green transition. The Just Transition Commission, as proposed in the Climate Action Plan, could and should play a key role in preparing and implementing policies to support a fair and socially inclusive green jobs transition. To start, Government must set out a clear, long-term vision and forward-looking strategy for green transition, aligning environmental policy with regional development, and, employment and skills policy with targeted supports for vulnerable groups.

[1]UNEP, ILO, IOE, ITUC (2008), Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low Carbon World.

[2] ILO (2022), What are green jobs according to the ILO?.