Greenhouse Gas Emissions going in the wrong direction

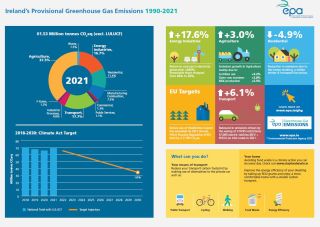

Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions increased by 4.7 per cent in 2021 compared to 2020 and are now 1.1 per cent above 2019 pre-COVID restriction levels according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s provisional greenhouse gas emissions for Ireland for 2021. In total in 2021, 61.53 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2eq) were emitted, with emissions 1.1 per cent above 2019 pre-COVID restriction levels. The increase is mostly due to a significant increase in emissions from the Energy Industries sector due to a tripling of coal and oil use in electricity generation in 2021, with increases also seen in the agriculture and transport sectors. We are not on the right track to meet our national or international obligations and commitments.

Summary of main trends

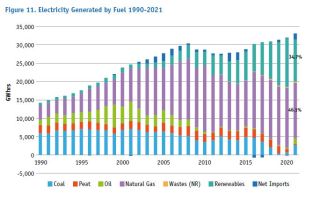

Energy

Emissions from the Energy Industries sector increased by 17.6 per cent in 2021, driven by a tripling of coal and oil use in electricity generation. The consumption of peat has continued to decline, by 67 per cent in 2021, and is currently at an all-time low within the power generation sector. There was also a reduction in natural gas use by 8.9 per cent as some plants were offline for a time in 2021. Electricity generated from renewables fell from 42 per cent in 2020 to 35 per cent, due to low rainfall and less wind. This resulted in an increase in the emissions intensity of power generation by 11.9 per cent in 2021.

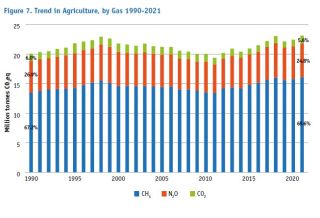

Agriculture

Agriculture emissions increased by 3.0 per cent in 2021, driven by increased fertiliser use (up 5.2 per cent) and a 2.8 per cent increase in the number of dairy cows and a 5.5 per cent increase in milk production. Agricultural emissions did not reduce during COVID restrictions and are now 15% higher than the 1990 level. This is the 11th consecutive year that dairy cow numbers rose. Milk output per cow also increased (by 2.5 per cent), therefore increased production was driven by a rise in livestock numbers in conjunction with an increase in milk yield per cow. In 2021, total cattle numbers increased by 0.8per cent. In 2021, liming on agricultural soils increased by 49.5 per cent, a welcome measure in improving soil fertility, which should lead to a reduction in fertiliser nitrogen use in future years.

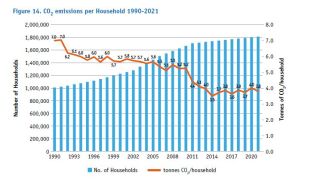

Residential

Residential greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 4.9 per cent in 2021, driven by a combination of less time in the home, a milder winter and increased fuel prices. However, emissions in 2020 had risen as a result of increased working from home. Emissions are now 2.8 per cent above pre-pandemic levels in this sector. A combination of warmer weather, rising fuel prices towards the end of the year and an easing of COVID restrictions contributed to substantial reductions in coal, peat and kerosene use for home heating. However, since 2014, fuel use per household has increased by 12 per cent with CO2 emissions per household at 3.8 t CO2 in 2021.

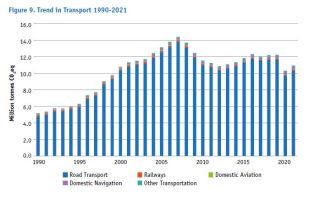

Transport

Transportemissions increased by 6.1 per cent as COVID-19 restrictions lifted, however emissions were 10.5 per cent below the pre-COVID 2019 level and it is unclear if they will rebound fully to that level. Road transport emissions increased from 9.7 Mt CO2eq in 2020 to 10.3 Mt CO2eq in 2021. At the end of 2021, there were just under 47,000 battery electric (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric (PHEVs) vehicles in Ireland, approximately 24 per cent of the Climate Action Plan target for 2025 of 195,300 and ahead of a linear uptake trajectory towards that target.

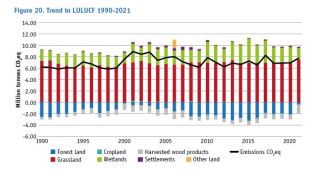

Land-Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULULCF)

Land-Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULULCF) comprises of six land use categories (Forest Land, Cropland, Grassland, Wetlands, Settlements, and Other Land) and Harvested Wood Products. When included in National total emissions (to assess progress against the National Climate Act target) this sector accounts for 11.2 per cent of the total emissions in 2021.

The LULULCF sector is a net source of CO2 eq emissions in all years 1990-2021. The main source of emissions is the drainage of grasslands on organic soils and the exploitation of wetlands for peat extraction. Forest land and Harvested wood products are a carbon sink (CO2 removal) for all years 1990-2021 although the carbon sink associated with Forest land is on a declining trend due to the age profile of existing forests and a declining afforestation trend.

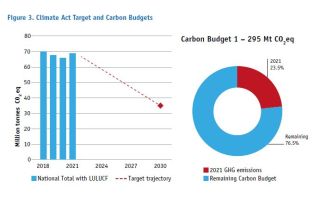

Carbon Budget

The Provisional greenhouse gas emission estimates for 2021 are a cause for concern in relation to achieving Ireland’s binding Carbon Budget targets. The current provisional numbers indicate that 23.5 per cent of the Carbon Budget for the 5-year period 2021-2025 has already been used. Staying within the current budget now requires deep emission cuts of over 8.4 per cent per annum over the period 2022 to 2025 to stay within budget.

Social Justice Ireland view

Reducing emissions requires the implementation of policy decisions made in the interest of a sustainable future rather than short-term sectoral interests. Ireland’s carbon budgets set out the emissions reductions required from each sector to 2030. As the EPA Provisional Greenhouse Gas Inventory for 2021 details, almost one quarter of the carbon budget to 2025 has already been used. Meeting these targets will be challenging for all sectors. Ambitious and substantive policies requiring sufficient resourcing and an all-of-Government approach are required to ensure that we meet our environmental targets. We are not limited in what we can do, but are limited by our political ambition and leadership, and by the fact that because we have left these decisions for so long, the effort required to achieve adaptation and transition will now be far greater than if we had acted years ago.

These commitments must be underpinned by ambitious and substantive policies requiring sufficient resourcing and an all-of-Government approach to ensure that we meet our environmental targets.

Progress towards changing farm practices has been limited and incentives to reduce on-farm greenhouse emissions have not been delivered on a wide scale. The agriculture and food sector must build on its scientific and technical knowledge base to meet the emissions challenge.

Transport is another area which faces challenging targets and transport continues to dominate Ireland’s energy use. Significant investment is needed to develop a public transport network powered by electricity and renewable energy. It is vital that the upgrade to the public transport network has a strong focus on connectivity to ensure that people travelling from rural or regional areas to urban centres are encouraged to do so by public transport. Government policy must also examine how to discourage private car use, particularly in urban areas, in conjunction with the provision of accessible and quality public transport and an improved cycling network all forming part of a transition to a low-carbon transport system.

Energy is the third largest driver of our emissions. Energy-efficient homes help reduce our carbon footprint as they require less fuel to heat. One of the most cost-effective measures to promote sustainable development is to increase building energy efficiency through retrofitting, for example. Recent announcements from Government to date in 2022 with regard to retrofitting are welcome, but large scale investment in infrastructure is required. Barriers still persist to accessing grants for low income households. These are the households who are most likely to use solid fuels such as coal and peat; the very households that policy should be targeting. The upfront costs associated with accessing sustainable energy grants can act as a barrier for those on low incomes. Too often subsidies are only taken up by those who can afford to make the necessary investments. These subsidies are functioning as wealth transfers to those households on higher incomes while the costs (for example, carbon taxes) are regressively socialised among all users. Incentives and tax structures must look at short and long term costs of different population segments and eliminating energy poverty and protecting people from energy poverty should be a key pillar of any Just Transition platform.

An upgrade of the national grid must be a key element of infrastructure investment so that communities, cooperatives, farms and individuals can produce renewable energy and sell what they do not use back into the national grid, thus becoming self-sustaining and contributing to our national targets.