Ireland and the EU face home care challenges

Ireland’s population is growing, and its composition is changing – it is getting older. Our increased longevity is a success story. The Programme for Government contains a welcome commitment to a statutory home support scheme which is expected to be come operational at the end of 2023. Ensuring adequate staffing and resourcing levels are two areas fundamental to the success of the scheme. As demand for home support services continue to rise, and this increase can be expected to continue in the long-term as the population ages, issues regarding resourcing the home support scheme, and ensuring adequate levels of staffing to deliver home supports to those who need it require urgent attention.

Ireland

A report examining strategic workforce challenges in home care settings and nursing homes was published in October 2022 in response to the well-documented challenges of recruitment and retention in the sector. The report notes that demand for home support services continues to rise.

Table 1: Home Support 2018 – 2022

Source: HSE Service Plans 2018-2022

*Figures exclude Intensive Home Care Packages

The report notes that at present publicly funded home-support services are currently provided free of charge by the HSE through Services for Older People and Disability Services based on a service-users’ assessed care-needs. The home-support services funded by the HSE’s Services for Older People primarily provide assistance with personal care as well as help with essential domestic tasks. These services are provided in two ways, directly by the HSE or indirectly through HSE commissioned home support services from not-for-profit and for-profit providers. As at July 2022, 62 per cent of home-support services were delivered indirectly and 38 per cent directly.

The report finds an acute shortage of care-workers against a background of rising demand for care. HSE data indicates that in July 2022, 5,312 people were waiting for home-support from the HSE’s Services for Older People because no care-workers were available to provide this. In addition the report notes that a significant proportion of care-workers providing home-support are themselves older people, with HSE data indicating 42 per cent were aged 60 and over. This is likely to exacerbate existing workforce shortages in the years to come. This echoes the situation across Europe where 38 per cent of the long-term care workforce are aged 50 and over.

The report makes a series of recommendations on recruitment for the care sector, including:

- There should be a national campaign to raise the profile and promote the training opportunities available for a career as a healthcare assistant and home-support worker.

- Public employment services should be reviewed with a view to further increasing the number of jobseekers who become healthcare assistants or home-support workers.

- The HSE should build its capacity for the timely, targeted, and locally focused recruitment of healthcare assistants and home-support workers, to include enhanced advertising of vacant roles. A rolling recruitment campaign should continue in each community healthcare organisation (CHO) for as long as positions remain unfilled.

- The Government should continue to hold European-level recruitment events and also increase awareness, and engagement, of the EURES network including on the supports available (e.g. relocation grants) amongst healthcare workers and providers.

- The HSE’s invitation to tender for the provision of home-support services should stipulate that approved providers should remunerate home-support workers for: a) time spent travelling between service-users’ homes b) any reasonable, vouched/certified travel expenses incurred.

- All private-sector and voluntary providers should be invited to give a commitment to pay home-support workers and healthcare assistants, at a minimum, the National Living Wage

- An appropriate mechanism to reach agreement in the private and voluntary sector in respect of pay and pensions for home-support workers and healthcare assistants shall be investigated and reported on by an Expert Working Group.

- A review should be undertaken of the eligibility criteria for State benefits with a view to ensuring that these do not disincentivise engagement in part-time employment.

- Home-support workers should be removed from the Ineligible Occupations List, enabling the employment within Ireland of non-EU/EEA citizens as home-support workers when regulations have been introduced.

- A competency framework for home-support workers and healthcare assistants should be developed to enable the recognition of prior learning and qualifications, to support career development, and to align grades of employment with qualifications in line with relevant regulations.

- There should be a significant increase in the proportion of home support hours and packages provided directly by the HSE. Targets determined by the HSE on a national level should be set out in the National Service Plan 2023.

- The HSE should develop a medium-term (3‒5 year) recruitment plan to give further effect to the recommendation on increasing direct provision of home-support.

Social Justice Ireland welcomes many of these recommendations, particularly those in relation to the Living Wage, increased supports in terms of education and training, quality frameworks and recognition of prior learning. However Social Justice Ireland is concerned that a focus on European-level recruitment events will simply exacerbate an existing problem whereby care workers from countries with poor care infrastructure are recruited to address shortfalls, resulting in a significant shortfall in LTC coverage for older people in these countries.

Europe

Ireland is not alone in facing an increasing age-dependency ratio and a shortfall of care-workers, many other European countries face similar challenges. Many of the challenges that Ireland faces are identified in the European Care Strategy published in September 2022. The number of persons potentially in need of LTC in the EU-27 is projected to rise from 30.8 million in 2019 to 33.7 million in 2030 and further to 38.1 million in 2050 with an additional 1.6 million long-term care workers required be added by 2050 simply to keep long-term care coverage at current levels which are already insufficient to meet demands. The European Care Strategy is a welcome first step towards the improvement of availability, accessibility and quality of LTC in all European countries. It aims to support delivery of Principle 18 of the European Pillar of Social Rights which states “everyone has the right to affordable long-term care services of good quality, in particular home-care and community-based services”.

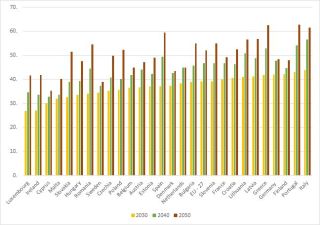

Old Age Dependency Ratio European Union, 2030, 2040, 2050* (Baseline Projections)

Source: Eurostat 2021 PROJ_19NDBI

All Member States see a gradual increase in old age dependency ratio to 2030, however between 2040 and 2050 all Member States see a significant rise. The increase is particularly marked in several countries with a projected ratio of 50 and above in Spain, Lithuania, Greece, Portugal and Italy in 2040, and a projected ratio of 60 and above in Spain, Greece, Portugal and Italy in 2050. The old age dependency ratio has particular implications for expenditure on pensions across the EU, and for expenditure on healthcare and long-term care, Not only does an increase in the old age dependency ratio mean there are less people of working age on each Member State to contribute to the exchequer requirements to fund pensions, healthcare and long-term care, it also means that the availability of informal carers is likely to decline and the available labour force for the long-term care sector will also be smaller.

This will put intense pressure on long-term care services across the EU, but particularly in those countries where there is a reliance on informal care to provide long-term care, and in those countries where there is no minimum wage or a very low minimum wage for workers in long-term care (LTC). Already there is a situation in Europe where the pool of available labour for long-term care in some countries is migrating to other countries in Europe where the wages and conditions are better (also referred to as the care drain). Five EU member states absorb almost two thirds of LTC foreign born workers; Germany, Italy, France, Spain and Sweden[1].

The data on demographics, and current and future LTC needs implies that the current levels of public investment are not sufficient to meet demand in Ireland, or across the EU.

[1] In 2018 there were almost 2 million health and LTC workers born in a country different than the one they were working in. The majority of these workers originated from a) other EU Member States; b) European countries not part of the EU; and c) the region of North Africa & Middle East.