Labour force trends

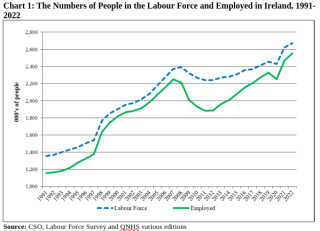

The dramatic turnaround in the labour market after 2007 [1] contrasts with the fact that one of the major achievements of the preceding 20 years had been the increase in employment and the reduction in unemployment, especially long-term unemployment. In 1991 there were 1,155,900 people employed in Ireland. That figure increased by almost 1.4 million to peak at 2,673,000 in 2022. During early 2005 the employment figure exceeded two million for the first time in the history of the state – a figure once again exceeded during late 2014; the figure is likely to exceed 2.7 million people in the years immediately ahead. Overall, the size of the Irish labour force has expanded significantly and today equals almost 2.7 million people; 1.4 million more than in 1991 (see Chart 1).

However, in the period after 2008 emigration returned, resulting in a decline in the labour force. Initially this involved recently arrived migrants returning home but was then followed by the departure of native Irish. CSO figures indicate that during the final quarter of 2009 the numbers employed fell below two million and that the level continued to fall until achieving some growth in late 2013 / early 2014 (Chart 1).

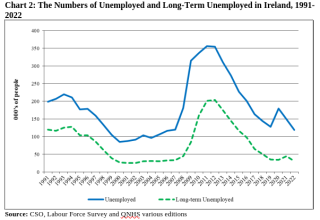

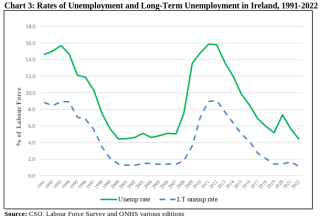

As Charts 2 and 3 show, the period from 1993 was one of decline in unemployment. By late-2000 Irish unemployment reached its lowest level at 3.8 per cent of the labour force. Subsequently the international recession and domestic economic crisis brought about increases in the rate. By 2006 unemployment had exceeded 100,000 on an annualised basis for the first time since 1999 with an average of 106,325 people recorded as unemployed in mid-2006. As Chart 2 shows, it exceeded 200,000 in early-2009, 300,000 in late-2009 and peaked at 356,000 in the third-quarter of 2011. The Covid-19 lockdowns caused further job losses with the numbers rapidly peaking and then declining again in 2020/21.

Unemployment has since declined, reaching a figure of 119,000 in late 2022. The chart also highlights the trends in the number of long-term unemployed (those unemployed for more than 12 months). The CSO reports that there were 34,300 people in long-term unemployment at the end of 2022; a figure which is still higher than in 2007.

Measuring the labour market

When considering terms such as ‘employment’ and ‘unemployment’ it is important to be as clear as possible about what we actually mean. Two measurement sources are often quoted as the basis for labour market data; the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and the Live Register.[2] The former is considered the official and most accurate measure of employment and unemployment, although it appears only four times a year. Given this, in recent years the Central Statistics Office (CSO) have also provided a monthly unemployment estimate which represents an estimate of changes to the LFS measure based on trends indicated by the numbers on the Live Register.

The CSO’s LFS unemployment data use the definition of ‘unemployment’ supplied by the International Labour Office (ILO). It lists as unemployed only those people who, in the week before the survey, were unemployed and available to take up a job and had taken specific steps in the preceding four weeks to find employment. Any person who was employed for at least one hour is classed as employed. By contrast, the live register counts everybody ‘signing-on’ and includes part-time employees (those who are employed up to three days a week), those employed on short weeks, as well as seasonal and casual employees entitled to Jobseekers Assistance or Benefit.[3]

Policy Proposals

Social Justice Ireland believes that Government should.

• Resource the up-skilling of those who are unemployed and at risk of becoming unemployed through integrating training and labour market programmes.

• Launch a major investment programme focused on prioritising initiatives that strengthen social infrastructure, including a comprehensive school building programme and a much larger social housing programme.

• Adopt policies to address the worrying issue of youth unemployment. In particular, these should include education and literacy initiatives as well as retraining schemes.

• Recognise the challenges of long-term unemployment and of precarious employment and adopt targeted policies to address these.

• Recognise that the term “work” is not synonymous with the concept of “paid employment”. Everybody has a right to work, i.e. to contribute to his or her own development and that of the community and the wider society. This, however, should not be confined to job creation. Work and a job are not the same thing.

[1] For more on this see Chapter 5 of Social Justice Matters: 2023 Guide to a Fairer Irish Society

[2] The LFS replaced the Quarterly National Household Survey (QNHS) from Q3 2017. The QNHS ran from late 1997 to 2017. Prior to this the CSO conducted an earlier version of the LFS.

[3] Healy, S. and Collins, M.L. (2006) “Work, Employment and Unemployment”, in Healy, S., B. Reynolds and M.L. Collins eds. Social Policy in Ireland: Principles, Practice and Problems. Dublin: Liffey Press.