National Risk Assessment ignores poverty pandemic

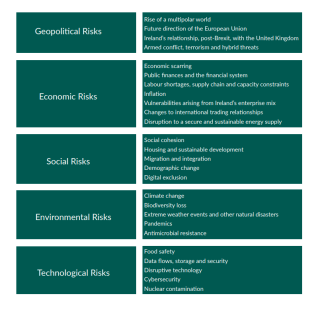

The Government of Ireland published the National Risk Assessment 2021/2022 (NRA) on Friday, 17th December 2021. The NRA was introduced post-2008 to provide an outline of the key risks for Ireland, as identified by Government, that may arise in the short-, medium-, and long-term. The Strategic Risks are categorised into five themes: Geopolitical Risks; Economic Risks; Social Risks; Environmental Risks; and Technological Risks, each with a set of key policy areas.

Fig.1: Strategic Risks 2021/2022

Source: National Risk Assessment, 2021/2022 p.11

Geopolitical Risks

Social Justice Ireland regrets that forced displacement did not feature as a risk. Forced displacement, whether due to conflict or climate change presents a serious risk for all countries. By the end of 2020, 84.2m people worldwide were forcibly displaced. 26.4m of these were refugees and 48m were internally displaced. Of the 40.5m new displacements in 2020, 30.7m were due to disasters, while just 9.8m were due to conflict. This suggests an increasing risk of displacement due to climate events. The largest number of displaced people are hosted by the Global South. Ireland, with a good track record on ODA, should seek to be a world leader, separating ODA from climate change-related supports and increasing overall provision.

Economic Risks

Social Justice Ireland welcomed the inclusion of labour market and sectoral-level challenges as key risks. We highlighted in this year's Employment Monitor that 21 per cent of people whose employment was affected by Covid-19 do not expect to return to the same job after the pandemic. In the absence of other employment opportunities, this suggests the potential for a transfer of these individuals from these schemes to jobseekers payments. A large increase in unemployment numbers seems inevitable; with rates of between 12 per cent and 16 per cent of the labour force possible. Furthermore, the pandemic is also likely to reveal a large youth unemployment problem.

Government needs to allocate resources to address these challenges and minimise the scale of the increase in unemployment and the growth of long-term unemployment. Specifically, we believe Government should:

- resource the upskilling of those who are unemployed and at risk of becoming unemployed through integrating training and labour market programmes.

- adopt policies to address the worrying issue of youth unemployment. In particular, these should include education and literacy initiatives as well as retraining schemes.

- expand the age profile for apprenticeships and training programmes to include older workers who may need to re-skill.

- recognise the challenges of long-term unemployment and of precarious employment and adopt targeted policies to address these.

- resource policies to address the obstacles that face women as they return to the labour market.

Social Risks

A critical social risk for Ireland is the persistent level of poverty and deprivation among the population. A fact ignored by Government in the development of the NRA. More than 660,000 people were living in poverty in 2020, 13.2 per cent of the population. Of these, more than 210,000 are children. The number, and rate, of people experiencing enforced deprivation is also a concern, with 781,794 (250,956 children) being forced to go without basic necessities due to lack of affordability. When the financial crash of 2008 happened, there were 43,000 fewer people at risk of poverty in Ireland. The impact of a decade of unnecessary austerity, and policy decisions which undermined the Social Contract, has deepened the divide between those people, businesses and sectors who will survive this latest economic shock and those who will not.

To give a real sense of income inequality in Ireland, one only has to look at the economic impact of the pandemic. While more than one in every seven people in the State were living on welfare payments, the wealth of Ireland’s five richest people rose by €4.3 billion in just one year. Income inequality and poverty are not just about money. They impact all other areas of our lives:

- The Covid-19 infection rates were 50 per cent or more higher in disadvantaged areas than in more affluent areas.

- Children and young people in disadvantaged areas have poorer health, lower levels of physical activity, poorer diets, and more emotional difficulties than their wealthier peers.

- Life expectancy is lower among disadvantaged groups than the national population and considerably lower than more affluent populations.

- Children in disadvantaged areas have poorer scores on standardised tests compared to their wealthier peers.

- Even with almost half a million people on the PUP, income tax receipts increased by 3.9 per cent in January 2021, compared to January 2020, indicating that it was the very lowest paid who suffered the most.

- Tenants in the private rented sector are more likely to be paying a higher proportion of their income in housing costs, experience deprivation and have less wealth than owner occupiers.

Policymakers must acknowledge that a thriving economy is not a goal in itself but a means to social development and wellbeing for all. Substantial evidence has emerged in recent decades to support the view that economies and societies perform better across a number of different metrics, from better health to lower crime rates, where there is less inequality.

Without the social welfare system almost two in five people in Ireland would have been living in poverty in 2020. Such an underlying poverty rate suggests a deeply unequal distribution of market income. In 2020 social welfare payments reduced the poverty rate by over 25 percentage points to 13.2 per cent. Over a decade ago, Budget 2007 benchmarked the minimum social welfare rate at 30 per cent of Gross Average Industrial Earnings (GAIE). Today that figure is equivalent to 27.5 per cent of the new average earnings data being collected by the CSO. In 2021 this would equate to €222.08 implying a shortfall of €14 between current minimum social welfare rates (€208) and this threshold.

Given the importance of this benchmark to the living standards of many in Irish society, and its relevance to anti-poverty commitments, the current gap highlights a need to close this gap. Core Social Welfare rates should be increased by €14 per week over the next two years.

Environmental Risks

Ireland has continuously failed to meet our environmental targets across a number of international benchmarks. While it encouraging that climate change, biodiversity loss, extreme weather events and disasters, pandemics and antimicrobial resistance have been acknowledged in the NRA, there are further areas that should be included:

Ensuring a sustainable recovery. Integrate a Sustainable Development Framework into economic policy. This would ensure that policies are socially, economically and environmentally sustainable. A sustainable development framework integrates environment, society and the economy in a balanced manner with consideration for the needs of future generations. Maintaining this balance is crucial to the long-term development of a sustainable resource-efficient future for Ireland.

Develop a new National Index of Progress. Government should develop a new National Index of Progress encompassing environmental and social indicators of progress as well as economic ones. This would involve moving beyond simply measuring GPD, GNI and GNI*, and including other indicators of environmental and social progress such as the value of unpaid work to the economy and the cost of depletion of our finite natural resources.

Investment must be underpinned by a Just Transition Strategy. One of the fundamental principles of a Just Transition is to leave no people, communities, economic sectors or regions behind as we transition to a low carbon future. Transition is not just about reducing emissions. It is also about transforming our society and our economy, and investing in effective and integrated social protection systems, education, training and lifelong learning, childcare, out of school care, health care, long term care and other quality services. Social investment must be a top priority of transition because it will support those people, communities, sectors and regions who will be most impacted as we transform how our economy and society operates.

Technological Risks

Social Justice Ireland welcomed the inclusion of digital literacy amongst the Social Risks in the NRA. While most schools are now equipped with a minimum level of digital technology, this does not mean that all schools are equal in this regard. OECD PISA research shows that, in Ireland, there is a significant digital divide for students in disadvantaged schools and these same students are less likely to have a quiet place to study, access to a computer for schoolwork, and school digital devices with sufficient capacity than their peers.

As schools were forced by circumstances to move to e-learning and digital technology this presented a significant concern that the digital divide in connectivity will exacerbate already existing educational inequalities. Educational disadvantage can be intergenerational. Students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are therefore less likely to have the support of parents with high levels of digital skills who can assist them in an online learning environment. This means that these students are at risk of falling further behind. This is borne out by the findings of research published by Maynooth University on the impact of COVID-19 and school closures at primary level.

Ireland already has an educational divide with outcomes for students in DEIS schools significantly below those of their peers, notwithstanding the progress made in recent years. Add to this the intergenerational transmission of low skills in Ireland, and it is evident that the move to online learning will have a negative impact on outcomes for students in disadvantaged schools. Ireland performs poorly in terms of digital skills. Less than half of the adult population has at least basic digital skills, well below the EU average (57 per cent). Only 28 per cent of people have digital skills above a basic level, below the EU average of 31 per cent. This general gap in digital skills is also confirmed by the OECD PIAAC survey of adult learning which is discussed in more detail below.

The move to digital learning and our low levels of adult digital skills will inevitably have a negative impact on our human capital and on the intergenerational transmission of educational outcomes. A report on Well-being in the Digital Age found that the digital transformation could compound existing socio-economic inequalities, with earnings and opportunities benefits accruing to a few, and the risks falling more heavily on people with lower levels of education and skills. The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the potential of digital technologies to exacerbate existing inequalities if we do not act now.