The Social Welfare Myth

In advance of Budget 2023, Social Justice Ireland and others called for an increase of €20 per week to core social welfare rates. This was considered "too expensive" by some politicians and commentators alike. There were debates about jobseekers' willingness to work and how much the State was willing to give people not to work. These debates are predicated on assumptions made about social welfare recipients. Assumptions that people who rely solely or mainly on social welfare are the only ones who receive it. And that "working people" (read here: those in employment) get nothing.

But this is not true. In fact, those in the top 10 per cent of the income distribution receive more in social transfers than those at the bottom.

As evident from the latest CSO SILC data, in 2022 social transfers, or social welfare, made a significant difference to the overall poverty rate in Ireland - reducing it from 36.7 per cent to 13.1 per cent, 23.6 percentage points.

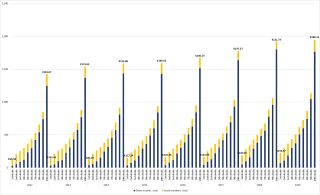

For people on the lowest incomes, social transfers make up the vast majority of their income. Analysis of the average weekly equivalised income by net disposable equivalised income deciles however, indicates that between 2012 and 2019, people in the top 10 per cent of the income distribution (the richest 10 per cent) received more in social transfers than those in the bottom (the poorest). In fact, as Chart 1 shows, in 2012 social transfers to the poorest 10 per cent amounted to just €96.48 per week compared to €181.07 per week to the richest 10 per cent. A gap of €84.59, meaning that the rich received 87.7 per cent more in social transfers per week than the poorest. This gap narrowed somewhat between 2012 and 2019, when the poorest 10 per cent received €156.37 compared to €180.12 to the richest (a gap of €23.75, 15.2 per cent more to the top 10 per cent).

Chart 1: Average Equivalised Income by Disposable Equivalised Income Deciles, 2012-2019

Source: Author's analysis of CSO SILC data 2012-2019, PxStat SIA36

While social transfers to the poorest 10 per cent increased by 62.1 per cent between 2012 and 2019, transfers to the richest 10 per cent remained almost the same, decreasing by 95c in that time. This is the case even where equivalised market incomes for the poorest increased from €26.44 per week in 2012 to €68.93 per week in 2019 (an increase of €42.49) and those for the richest increased by €519.82 to €1,764.08 per week.

What are Social Transfers?

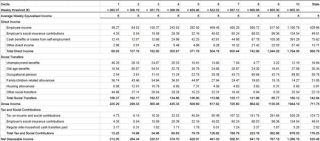

For the time period specified, 2012-2019, social transfers included unemployment benefits, old-age benefits, occupational pensions, family/children related allowances, housing allowances, and other social transfers. Table 1 shows that, in 2019, the poorest 10 per cent received approximately 4 times the amount of unemployment benefits of the richest, while the richest received twice the old-age benefits of the poorest (likely as a result of their higher life expectancy). The largest difference is in occupational pensions, with the poorest receiving just €2.04 per week compared to the richest who receive €89.92 per week.

Occupational pensions were included within social transfers, according to a Background Note published by the CSO, using a European-wide definition of social transfers up to 2019. Since 2020, however, the CSO moved to a national definition of social transfer, which excludes occupational pensions. Occupational pensions, notwithstanding the large tax reliefs available to recipients in respect of pension contributions, have been classified as market income since 2020.

However, even without occupational pensions, the richest 10 per cent of the population received €90.20 per week in social transfers in 2019.

Table 1: Average weekly equivalised income by net disposable equivalised income deciles and composition of net equivalised disposable income, 2019

Source: CSO, Survey on Income and Living Conditions 2019, Table 2.6

Who Pays for Social Transfers?

While it is fair to say that Ireland's income tax system is progressive, with the richest paying more in income taxes and social contributions than the poorest, it is inaccurate to say that the poor contribute nothing. Further analysis of Table 1 above indicates that the poorest 10 per cent pay 5.4 per cent of their gross income (which includes social transfers) in tax and social contributions, €12.25 per week. This amounts to 7.8 per cent of the social transfers they receive. This does not include VAT or other indirect taxes.

The richest 10 per cent pay 34.9 per cent of their gross income (including social transfers) in tax and social contributions, 3.75 times their social transfers. However, as old-age benefits and occupational pensions, which both disproportionately benefit the rich, are paid into older age, it is possible that the richest 10 per cent will be net beneficiaries, or at least not significant losers, of the social welfare system by the time they die, and that is without accounting for any tax reliefs availed of on pensions, shares, property and so on.

Social Justice Ireland Position

We believe that all people should have sufficient income to live life with dignity. In 2022, some 671,000 people were living on incomes below the poverty line. Without social transfers, that figure would be closer to 2 million. Inequality has risen to a level where the richest 10 per cent now have four times the equivalised income of the poorest 10 per cent. The social welfare system needs to support those who need it most. In our release following the publication we called on Government and policymakers to implement the following policies:

- Immediately provide for an additional €8 per week (€20 in total) in core social welfare rates.

- Acknowledge that Ireland has an on-going poverty and deprivation problem.

- Adopt targets aimed at reducing poverty and deprivation among particularly vulnerable groups such as children, lone parents, jobless households, and those in social housing.

- Examine and support viable alternative policy options aimed at giving priority to protecting vulnerable sectors of society.

- Benchmark core social welfare rates to 27.5 per cent of average weekly earnings.

- Carry out in-depth social impact assessments prior to implementing proposed policy initiatives that impact on the income and public services on which many low-income households depend. This should include the poverty-proofing of all public policy initiatives.

- Recognise the problem of the ‘working poor’. Make tax credits refundable to address the situation of households in poverty which are headed by a person with a job.

- Support the widespread adoption of the Living Wage so that low paid workers receive an adequate income and can afford a minimum, but decent, standard of living.

- Introduce a cost of disability allowance to address poverty and social exclusion of people with a disability.

- Recognise the reality of poverty among migrants and adopt policies to assist this group. In addressing this issue, replace direct provision with a fairer system that ensures adequate allowances are paid to asylum seekers.

- Accept that persistent poverty should be used as the primary indicator of poverty measurement and assist the CSO in allocating sufficient resources to collect this data.

- Move towards introducing a basic income system. No other approach has the capacity to ensure all members of society have sufficient income to live life with dignity.

- Acknowledge the failure to meet repeated policy targets on poverty reduction and commit sufficient resources to achieve credible new targets.

We would add to this list, the recognition that everyone benefits from social transfers at some stage of the life cycle, and the rich more than most at times.

According to the CSO:

Equivalence scales

Equivalence scales are used to calculate the equivalised household size in a household. Although there are numerous scales, the CSO focus on the national scale in the SILC. The national scale attributes a weight of 1 to the first adult, 0.66 to each subsequent adult (aged 14+ living in the household) and 0.33 to each child aged less than 14. The weights for each household are then summed to calculate the equivalised household size.

Equivalised disposable household Income

Disposable household income is divided by the equivalised household size to calculate equivalised disposable income for each person, which essentially is an approximate measure of how much of the income can be attributed to each member of the household. This equivalised income is then applied to each member of the household.