Wellbeing in Recovery - The OECD Covid-19 Dashboard for Ireland

The OECD has recently released its Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, a selection of twenty indicators that aims to monitor the recovery of OECD countries from the pandemic. Spread across four dimensions - Strong, Inclusive, Green, and Resilient - the data corresponds with what the OECD terms the four key priorites that OECD Members agree should characterise Covid-19 Recovery. So, how does Ireland fare?

According to the OECD, the Dashboard was built at the request of OECD Ministers to "keep track of national efforts to build back better.". The Dashboard consists of twenty indicators across four dimensions determined by the OECD as those that matter to people, the economy and the planet.

What are the four dimensions?

According to the OECD, the dimensions of the Dashboard correspond to the four key priorities that OECD Members agreed should characterise the COVID-19 recovery. Each of these dimensions features five indicators to track progress:

The Strong dimension assesses the impact of the pandemic on the economic prosperity of households and businesses and monitors immediate signals of the state of the health crisis and the revival of economic activity.

The Inclusive dimension focuses on how the crisis has affected the income and jobs of the most vulnerable, and whether efforts to build back better are ensuring that economies and societies create equal opportunities for all.

The Green dimension focuses on progress towards achieving a people-centred green transition, consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda.

The Resilient dimension focuses on the factors that can help countries to better withstand the crisis and prepare for future challenges.

Data is collected by national statistics offices (such as the CSO in Ireland) and, where timely statistics capable of measuring the recovery are not available, data from the Gallup World Poll is used instead. The Dashboard also uses some experimental data, such as weekly estimates for year-on-year GDP growth, based on Google Trends data.

How does Ireland's recovery fare?

To answer this question, we need to look at each of the four dimensions and their five corresponding indicators.

Strong

This dimension is made up of Economic Activity, measured by GDP growth; Household Income, measured by Household disposable income per person; Excess Deaths, measured in terms of the mortality rate compared to the average in the period 2015 to 2019; and Hours worked, measured by the percentage change in total volume of hours worked in the previous year.

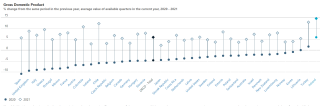

Economic Activity

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

GDP in Ireland rose 14.42 per cent in the year to 2021, and 5.86 per cent the previous year. As can be seen from the Figure above, this is higher than the OECD average (5.86 per cent in 2021 and -4.66 per cent in 2020). While this is one indicator of economic activity, the difficulties with measuring growth in terms of GDP, particularly in an Irish context, have been almost universally acknowledged.

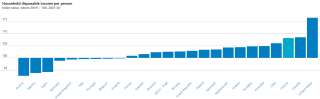

Household Income

This is measured in terms of Household disposable income per person, indexed to 2019. It captures the income that households have at their disposal after paying direct taxes and social contributions and after receiving monetary transfers from the government. In-kind transfers are not included. As can be seen below, Ireland's Q1 2021 household income compares favourably with other OECD countries, placing third behnd the United States and Canada. Yet we know that, in 2020, 13.2 per cent of the population (almost 650,000 people) in Ireland were living below the poverty line.

What is behind this seeming inconsistency? According to the CSO, while Total Gross Disposable Income of households grew by €9.3bn in 2020, the growth was unevenly distributed. €8.8bn in pandemic-related State supports is included in these income figures, €5bn in respect of the Pandemic Unemployment Payment (PUP) and €3.8bn in the Employee Wage Subsidy Scheme (EWSS) with analysis from the CSO indiciating that those in receipt of these supports had a lower median income than before the pandemic.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Excess Deaths

The indicator used here is the mortality rate compared to the average in the period 2015 to 2019. Unfortunately, there is no return for Ireland within the OECD Dashboard for comparison purposes, however a CSO Frontier Series Output, released in April 2021, provided an experimental analysis of data from RIP.ie to analyse trends in mortality. Using a simple calculation to provide a range of excess deaths, by calculating the expected number of death notices from March 2020 to February 2021 as either

- The same as the number of death notices in the previous year

- The average of the last 2 years

- The average of the last 3 years

the CSO calculated a range of excess deaths of between 2,034 and 2,338 in this period. Further analysis of the numbers of deaths reported on RIP.ie and the number of Covid-related deaths also shows a clear correlation between the number of deaths overall and the peaks and troughs of the pandemic.

Hours Worked

Calculated as a percentage change in the total volume of hours worked from the same period in the previous year, the number of hours decreased by 3.05 per cent in the year to 2020 and increased by 4.67 between 2020 and 2021 (see below). The number of hours worked in 2020 represented a decrease of 6.6 million hours on the previous year. The latest Labour Force Survey data, for Q3 2021, suggests an increase of 4.3 million hours on the previous year, a gap of 2.3 million to be made up in the last quarter of the year to return to 2019 levels.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Data in respect of New Enterprise Creations and Bankruptcies of Enterprises are not available for Ireland to complete the Strong dimension.

Inclusive

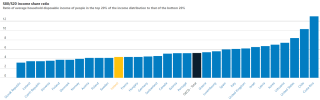

The first metric used here is that of Income Inequality, measured on the basis of the S80/S20 income share ratio, a ratio of averge household disposable income of people in the top 20 per cent of the income distribution to the average household disposable income of people in the bottom 20 per cent. Here, Ireland appears to be doing relatively well, with a ratio of 4.4, compared to an OECD Total of 5.24 (see below).

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

The Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) is where we get our latest data on income inequality. The latest data available indicates that, in 2020, the proportion of the equivalised disposable income received by the top 20 per cent of recipients was 37.9 per cent, compared to a share of just 9.2 per cent for those in the bottom 20 per cent.

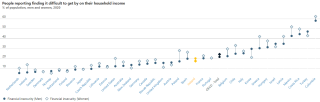

Financial Insecurity

The next metric used by the OECD Dashboard looked at People reporting finding it difficult to get by on their household income, by percentage of men and women. Ireland is in the mid-to-high range here, at 20.03 per cent of men and 17.37 per cent of women, compared to an OECD Total of 21.59 per cent and 24.19 per cent respectively (see below). In 2020, 15.6 per cent of the population were defined as living in some form of enforced deprivation, almost 782,000 people. The proportion of men and women reporting finding it difficult to get buy on their household income is lower in the OECD data than the deprivation data set out in SILC (14.7 per cent and 16.4 per cent respectively), indicating that people may be struggling and not captured within the definition of enforced deprivation used.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

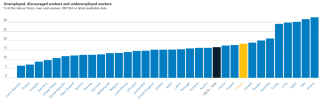

Labour Utilisation is measured by the proprotion of the labour force, both men and women, who are unemployed, discouraged workers and underemployed workers. Ireland has a comparatively high level of underutilisation compared to other countries within the OECD, at 18.38 per cent of the labour force compared to 16.48 per cent of the OECD total. An increase in job precarity pre-Covid, coupled with job losses and reductions in hours resulting from the pandemic are factors here. Greater protections for workers, flexible working, on-the-job upskilling and lifelong learning would help support workers to full employment.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

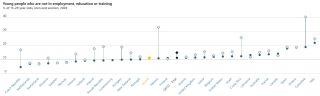

NEETs, Young People Not in Employment, Education or Training is the next metric used by the OECD in determining inclusion. Ireland's NEET rate, at 10.65 per cent of men and 11.39 per cent of women is lower than the OECD Total, at 11.27 per cent and 14.96 per cent respectively (see chart below). However, despite making steady progress, Ireland still faces challenges in the area of early school leaving and young people not engaged in employment, education or training in disadvantaged areas. This problem is likely to be exacerbated by the impact of Covid-19 with the disruption in their access to education and employment opportunities likely to make it more challenging for the younger generation to maintain quality jobs and income (OECD, 2020b). Providing support and opportunities for young people not engaged in employment, education or training must be a priority for Government or we risk creating a generational divide. The gap between retention rates in DEIS and non-DEIS schools has halved since 2001, but it still stands at 8.5 per cent. Government must work to ensure that schools in disadvantaged areas are supported to bring the rate of early school leavers to below Ireland’s country-specific target of 8 per cent under the EU2020 Strategy and towards the national rate of 4 per cent. Overall, we believe that the situation calls for a long-term policy response, which would encompass alternative approaches aimed at ensuring that people who leave school early have alternative means to acquire the skills required to progress in employment and to participate in society. The recent Action Plan for Increasing Traveller Participation in Higher Education contains a broader view of access and recognises the need to support traditional and non-traditional routes to higher education. This broad view of access is pertinent when it comes to dealing with the issue of early school leaving.

The longer a person stays in education the more likely they are to be in employment. The risk of unemployment increases considerably the lower the level of education. Participation in high quality education has benefits not only for young people themselves but also for taxpayers and society. These benefits typically last over the course of an individual’s lifetime. According to the OECD adults with a tertiary degree in Ireland earn on average 81 per cent more than adults with upper secondary education. They are more likely to be employed, the employment rate is 11 percentage points higher for degree holders than for those with an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education.

Socio-economic disadvantage also follows a student throughout the education system with younger graduates from more affluent areas earning around €2,000 more a year on average than their peers from disadvantaged areas. Even when controlling for different factors, graduates from disadvantaged backgrounds earn more than €600 less after graduation than others.

This presents a challenge to policymakers, and points to the value of investing in education at all stages, and the particular importance of investing in early childhood education, and a continued focus on tackling educational disadvantage. The benefits of investing in education, both to the individual, to the economy and to society, far outweigh any initial outlay of resources. This is something that should be at the forefront of decisions regarding the investment and resourcing of our education system as a whole.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

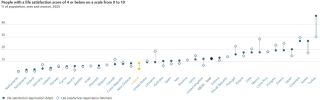

The final metric under Inclusion is Life Satisfaction, measured as the percentage of the population with a life satisfaction score of four or below on a scale from 0 to 10. Ireland compares favourably on this score with 8.57 per cent of men and 3.95 per cent of women, compared to an OECD total of 12.58 per cent and 12.17 per cent respectively (see below).

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Green

Ireland is a self-professed laggard when it comes to climate action. Having been instrumental in developing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), we have consistenty missed targets on emissions reductions and are actively going in the wrong direction by showing an increas in emissions and bucking a European trend of a downward trajectory.

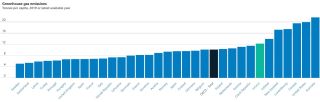

The first metric within this dimension of the OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard is Greenhouse gas emissions, measured in tonnes per capita as at 2019 or latest year available. As can be seen from the chart below, Ireland's emissions are among the highest in the reported OECD countries, at 12.24 tonnes per captia compared to an OECD Total of 10.12 tonnes per capita.

Since the collection of this data, Government has introduced a range of policy measures to address the climate emergency.

- The Programme for Government commits to an average 7% per annum reduction in overall greenhouse gas emissions from 2021 to 2030 (a 51% reduction over the decade), and to achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

- Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Act 2021 established a legally binding framework with clear targets and commitments set in law, and ensure the necessary structures and processes are embedded on a statutory basis to ensure Ireland achieves national, EU and international climate goals and obligations in the near and long term. The Act contains a provision that the first two five-year carbon budgets proposed by the Climate Change Advisory Council should equate to a total reduction of 51% emissions over the period to 2030.

- The Climate Change Advisory Council (the Council) has submitted its proposal for Ireland’s first carbon budget programme on the 25th of October. The programme is broken down into three five-year carbon budgets. Carbon budgets prescribe the maximum amount of greenhouse gases that may be emitted over a specific period of time in the State.

- The first two carbon budgets in the programme provide for the 51% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the state by 2030 relative to 2018 as set out in the Climate Action and Low-Carbon Development (Amendment) Act.

- The annual Average Percentage Change in Emissions from the first carbon budget 2021-2025 is a reduction of 4.8%, the second carbon budget 2026-2030 sees a reduction of 8.3%, and the third budget 2031-2035 sees a reduction of 3.5%.

- The first carbon budget has built in the implications of the time-lag between making decisions and investments on the one hand, and on the other hand, seeing the emissions reductions come into effect.

The Climate Action Plan will set out exactly what policies will be enacted to get us there.

There are also European targets. As a member of the EU, Ireland has committed to legally binding emissions reduction targets in 2020 and 2030. We have committed to a 20 per cent reduction on 2005 emission levels by 2020, and a 30 per cent reduction of emissions compared to 2005 levels by 2030. Ireland will not meet the 2020 target and we are certainly not on a trajectory to make our 2030 targets. The European Commission has also committed to a net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, a substantial increase on the previous target of a 40% reduction. Ireland must make a contribution to this target

- Provisional greenhouse gas emissions published by the Environmental Protection Agency for 2020 show that Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 3.6 per cent in 2020, less than the reduction seen in 2019.

- Lockdown measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a 15.7 per cent decrease in Transport emissions, the largest sectoral emissions reduction.

- Peat fuelled electricity generation decreased by 51 per cent in 2020. Together with a 15 per cent increase in wind generation - this led to a 7.9 per cent reduction in Energy Industry emissions.

- Residential greenhouse gas emissions increased by 9.0 per cent, with a substantial increase in carbon intensive fossil fuel use driven by low fuel prices and working from home.

- Agriculture emissions increased by 1.4 per cent in 2020, driven by increased activity in all areas, including a 3.2 per cent increase in the number of dairy cows.

- While the overall reduction in emissions of 3.6 per cent is welcome, the majority of the reduction was due to a short term decrease in transport emissions due to the Covid 19 pandemic, which is likely to be once-off.

To deliver on our climate targets, Government has committed to a Green New Deal for Ireland and a Just Transition in the Programme for Government.

One of the fundamental principles of a Just Transition is to leave no people, communities, economic sectors or regions behind as we transition to a low carbon future. Transition is not just about reducing emissions. This is just one part. It is also about transforming our society and our economy, and investing in effective and integrated social protection systems, education, training and lifelong learning, childcare, out of school care, health care, long term care and other quality services, Social investment must be a top priority of transition because it is this social investment that will support those people, communities, sectors and regions as we make the difficult transition to a carbon-neutral economy, transforming how our economy and society operates.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Renewable Energy, as a percentage of primary energy supply, is also measured as part of the Green dimension. Again, Ireland lags behind with just 11.59 per cent of primary energy supplied by way of renewables in 2019 (or latest year available) compared to an OECD Total of 21.63 per cent (see chart below).

The latest Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) report ‘Energy In Ireland 2020’notes that although Ireland has reduced its dependence on imported energy, the increase in our domestic energy generation is primarily from natural gas which is a fossil fuel. This runs contrary to our targets of reducing emissions, increasing renewable energy, and eliminating our dependence on fossil fuels. In 2019 renewables made up 12 per cent of final energy consumption, and our 2020 target is 16 per cent. Ireland is unlikely to meet our 2020 target and needs to do significantly more to produce renewable energy in order to meet our 2030 target.

Investment in renewable energy and retrofitting on the scale required to meet our national climate ambition requires large scale investment in infrastructure. An upgrade of the national grid must be a key element of infrastructure investment so that communities, cooperatives, farms and individuals can produce renewable energy and sell what they do not use back into the national grid, thus becoming self-sustaining and contributing to our national targets.

The issues around renewable energy subsidies and energy poverty must be addressed. Too often subsidies are only taken up by those who can afford to make the necessary investments. Retrofitting is a prime example. As those who need them most often cannot avail of them due to upfront costs, these subsidies are functioning as wealth transfers to those households on higher incomes while the costs (for example carbon taxes) are regressively socialised among all users. Incentives and tax structure must look at short and long term costs of different population segments and eliminating energy poverty and protecting people from energy poverty should be a key pillar of any Just Transition platform. A state led retrofitting scheme is required to ensure that people living in social housing and poor quality housing have access. This would increase energy efficiency, reduce bills, improve health outcomes, and assist us in meeting our climate-related targets.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

According to the OECD, the use of raw material resources by the economy puts pressure on natural ecosystems, both domestically and abroad. Moves in this regard to introduce a Circular Economy Package have not yet been fully implemented in Ireland. The 2018 Circular Economy Package includes a Europe-wide Strategy for Plastics in the Circular Economy; a communication on options to address the interface between chemical, product and waste legislation; a Monitoring Framework on progress towards a circular economy; and a Report on Critical Raw Materials and the circular economy. The Monitoring Framework is particularly instructive in that it ‘puts forward a set of key, meaningful indicators which capture the main elements of the circular economy’. Changing from a linear economy to a circular one presents a challenge across all sectors, but bears rewards from an economic, environmental and social standpoint. The monitoring framework attempts to deal with this systemic challenge through the development of these key indicators which take a cross-sectoral view of progress, grouping the ten indicators into four aspects of the circular economy: production and consumption, waste management, secondary and raw materials, and competitiveness and innovation. The monitoring framework goes on to provide examples of each of the indicators and the EU levers, where possible.

According to the OECD, Ireland uses 24.68 tonnes per capita, among the highest of all OECD countries (see chart below).

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Air pollution is measured in terms of the percentage of the population exposed to more than 10 micrograms per cubic metre of PM2.5 in 2019. This indicator presents the share of people living in areas with annual concentrations of fine particulate matter of less than 2.5 microns in diameter exceeding the WHO Air Quality Guideline value of 10 micrograms per cubic metre. Ireland has one of the lowest rates of air pollution as measured in this way, at 0.6 per cent, compared to an OECD Total of 61.67 per cent (see chart below).

Notwithstanding this, according to the EPA about 1,300 premature deaths annually in Ireland can be attributed to air pollution. Those most impacted include older adults, people with chronic illnesses, children and those living in deprived communities. The World Health Organisation has described air pollution as the ‘single biggest environmental health risk’. EPA figures show that air pollutants were above the WHO’s guideline values for health at 33 monitoring stations across Ireland in 2019 – mostly as a result of the burning of solid fuel in our cities, towns and villages.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

The final metric used under the Green dimension is in respect of natural and semi-natural vegetated land. Natural and semi-natural vegetated land is defined by the OECD as land covered by trees, grassland, wetland, shrubland and sparse vegetation. This is measured as an index value for 2019, benchmarked to 2004. Ireland's position has remained static, at 99.93, the same as the OECD Total (see chart below).

However, the EPA’s 2017 report repeats earlier assertions that the economic value of our ecosystem services is around €2.6 billion but that the rate of habitat degradation and loss of biodiversity is accelerating across Europe, including in Ireland. Ireland needs to improve its data collection methods when it comes to biodiversity and to monitor the impact of climate change in this context to protect both our natural resources and our economy. Our natural capital and ecosystems should also be assigned value in our national accounting systems.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Transition to a sustainable economy can only be successful if it is inclusive and if the social rights and wellbeing of all are promoted. A Just Transition requires a social protection system – along with appropriate services and infrastructure – that prevents poverty and social exclusion for those that lose employment or income due to the effects or mitigation of climate change.

Resilient

The final dimension used in the Dashboard is Resilient. This asks the questions "Are economies and societies becoming more capable of confronting risks such as the COVID-19 pandemic? And are they ready to face the challenges of the future?" and considers some of the factors viewed by the OECD to be important to support the preparedness of economies and societies against future shocks.

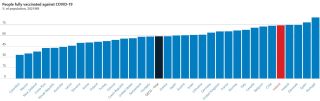

The first metric here is, somewhat understandably, Covid-19 Vaccination Rate as a percentage of the population in 2021 M9. Here, Ireland fares quite well in being among the top five vaccinated countries, with 74.34 per cent, compared to the OECD Total of 59 per cent (see below). But in Ireland, as elsewhere, the impact of the pandemic was not universally felt. Areas with fewer resources and higher rates of precarious and low-paid employment saw higher incidence rates than their more affluent counterparts. We must work harder to address health inequalities and ensure that the level of care received is directly related to the level of need, not the ability to pay.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Investment

The metric used by the OECD to measure Investment is the level of Gross fixed capital formation, indexed to 2019, in 2021 Q2 or latest available quarter. According to the OECD, Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) captures both public and private investment in the economy. This indicator presents total investment in dwellings, structures, machinery and equipment, alongside investment in intellectual property assets, which includes spending in Research and Development, computer software and databases, entertainment, literary and artistics originals. As can be seen from the chart below, Ireland's performance in terms of total GFCF is the poorest, literally off the charts. When confined to Intellectual Property, our GFCF is still among the lowest and ranks behind the OECD Total.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Broadband Coverage

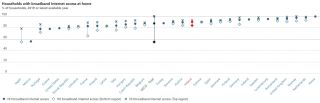

Access to high-speed internet should be seen as an essential component to participation in modern society, particularly after the experience of the last 23 months when the work, education and many services all transferred online. It is an essential economic, social and educational inclusion tool that enables people to fully participate in society and remain connected and informed. It will be important to ensure ease and equality of access so that already disadvantaged or marginalised groups do not fall further behind.

More than a decade ago, the European Commission recognised that ‘Digital literacy is increasingly becoming an essential life competence and the inability to access or use ICT has effectively become a barrier to social integration and personal development. Those without sufficient ICT skills are disadvantaged in the labour market and have less access to information to empower themselves as consumer, or as citizens saving time and money in offline activities and using online public services’. Over ten years later, there are still areas in (particularly rural) Ireland who continue to be disadvantaged in this way, with the digital divide further exacerbating educational disadvantage in areas with poor connectivity.

According to the OECD Data, Ireland's overall proportion of household broadband internet access stands at 89.33 per cent, ranging from 84 per cent in the bottom region to 93 per cent in the top region (see below). While this is better than the OECD Total, there remains a gap of nine percentage points between those regions at the bottom and those at the top. Some 16 per cent of households in the bottom are without this necessity.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

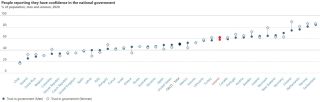

Trust in Government

According to the OECD, people's trust in their government is an indication of broader societal resilience. The proportion of Irish men and women who reported having confidence in the national government in 2020 is compartively quite high by international standards, with 58.01 per cent of men and 62.07 of women (see chart below). These data are gathered using the Gallup World Poll which had a break in the time series in 2019 and, according to the OECD, be interpreted with caution.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

A similar question is asked of Member States as part of the European Union's Eurobarometer, a polling instrument to monitor the state of public opinion in Europe on political and societal issues. According to the latest Standard Eurobarometer for Spring 2021, published in September 2021 just 48 per cent of the population tended to trust the Irish Government and 47 per cent tended to trust the Irish Parliament. When asked what the two most important issues facing Ireland were at the moment, 59 per cent said Housing and 44 per cent said Health. Two areas on which the Irish Government is not delivering.

Debt

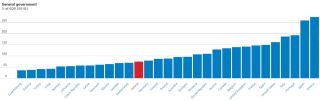

Debt is considered under three headings: general government debt as a percentage of GDP; non-financial corporations' debt as a percentage of GDP; and debt as a percentage of net household disposable income.

In Q1 2021, Ireland's general government debt was 74.52 per cent of GDP. This positions Ireland near to the middle of the OECD countries, however it is interesting to note that countries such as Germany, Austria and Japan have higher debt to GDP ratios than Ireland (see below). Ireland's approach to taking on debt to address the structural and societal damage of the pandemic has been conservative. Rather than borrowing at historically low rates to rebuild the social contract and put the necessary investment into infrastructure and services (housing, healthcare, education, just transition to name but a few areas that are in need), the Government's approach has been to borrow less than is required.

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Debts of Non-Financial Corporations (NFCs) is also used to quantify financial resilience. Ireland's NFC in Q1 2021 was 112.47 per cent of GDP, slightly lower than the OECD Total (115.79 per cent) (see chart below).

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Source: OECD Covid-19 Recovery Dashboard, Ireland

Finally, the OECD considers the position of household debt, measured as a percentage of net household disposable income. A similar picture emerges here in that Ireland is near the middle of the chart, below the OECD-Total, at 112.47 per cent compared to 115.79 per cent (see below). Of course not all households will have experienced the financial impact of Covid equally. Many households will have sought rent freezes or mortgage payment breaks, increasing their overall future debt. Many will have experienced job losses or reductions in income and/or working hours and will have difficulty making debt repayments.

Conclusion

Based only on the metrics used in the OECD Covid-19 recovery dashboard, Ireland's recovery is underway, with the notable exception of the Green dimension. However, underpinning many of the metrics used is a deep societal and economic inequality which persists, which cannot be fully appreciated from the population-level statistics or data based on GDP.