Youth poverty across the EU

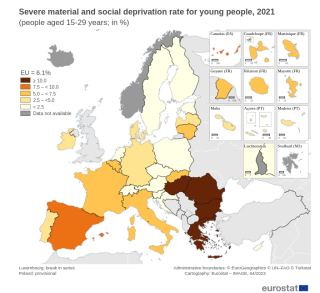

New figures from Eurostat show that 6 per cent of EU youth are classed as severely materially and socially deprived. In 2021, across the EU, the social deprivation rate for the population as a whole stood at 6.3 per cent and for those aged between 15 and 29, it was 6.1 per cent.

The severe material and social deprivation rate in the EU is an EU-SILC indicator that shows an enforced lack of necessary and desirable items that are needed to lead a basic standard of living. It is defined as the proportion of the population experiencing an enforced lack, having to go without at least 7 out of 13 deprivation items (6 items relate to the individual and 7 relate to the overall household). The indicator is part of the at risk of poverty or social exclusion rate as defined in the framework of the EU 2030 target on poverty and social exclusion.

The list of items relating to the household are:

The capacity to face unexpected expenses.

The capacity to afford paying for one week annual holiday away from home.

The capacity to being confronted with payment arrears (on mortgage or rental payments, utility bills, hire purchase instalments or other loan payments).

The capacity to afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish or vegetarian equivalent every second day.

The ability to keep home adequately warm.

To have access to a car/van for personal use.

The ability to replace worn-out furniture.

The list of items than at an individual level are:

Having internet connection.

Replacing worn-out clothes by some new ones.

Having two pairs of properly fitting shoes (including a pair of all-weather shoes).

Spending a small amount of money each week on oneself.

Having regular leisure activities.

Getting together with friends/family for a drink/meal at least once a month.

Among the EU countries,in 2021, Romania reported the highest proportion of young people who were severely materially and socially deprived with 23.1 per cent, followed by Bulgaria at 18.7 per cent and then Greece at 14.2 per cent. At the other end of the scale, the proportion was less than 3 per cent in 11 of the 26 EU members with the available data. These were Luxembourg, Poland, Sweden, Cyprus, Czechia, Netherlands, Croatia, Slovenia, Finland, Austria, and Estonia. Ireland reported 4.2 per cent.

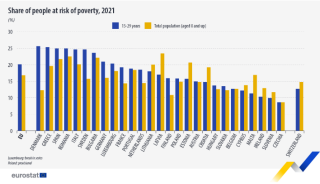

At-risk-of-poverty rate of young people

In 2021, the at-risk-of-poverty rate in the EU was higher for young people aged 15-29 at 20.1 per cent, than for the total population, at 16.8 per cent.

This was the case across 19 EU countries, with the biggest gap between the two observed in Denmark (12.3 per cent of the total population at risk of poverty compared with 25.6 per cent of young people) and Sweden (15.7 per cent compared with 24.6 per cent). The opposite was the case in eight EU countries. Young people were less at-risk of poverty than the population as a whole. The most noticeable differences were seen in Latvia (23.4 Per cent of the total population at risk of poverty compared with 17.0 per cent of young people), Malta (16.9 per cent compared with 11.3 per cent), Estonia (20.6 per cent compared with 15.7 per cent) and Croatia (19.2 per cent compared with 14.7 per cent). In Ireland, the percentage for the population as a whole was 12.9 per cent and 10.3 for those aged between 15 and 29.

Policy recommendations:

If poverty and deprivation rates are to fall in the years ahead, Social Justice Ireland believes that in the period ahead Government, and policymakers generally, should:

- Immediately provide for an additional €8 per week (€20 in total) in core social welfare rates.

- Acknowledge that Ireland has an on-going poverty and deprivation problem.

- Adopt targets aimed at reducing poverty and deprivation among particularly vulnerable groups such as children, lone parents, jobless households, and those in social housing.

- Examine and support viable alternative policy options aimed at giving priority to protecting vulnerable sectors of society.

- Benchmark core social welfare rates to 27.5 per cent of average weekly earnings.

- Carry out in-depth social impact assessments prior to implementing proposed policy initiatives that impact on the income and public services on which many low-income households depend. This should include the poverty-proofing of all public policy initiatives.

- Recognise the problem of the ‘working poor’. Make tax credits refundable to address the situation of households in poverty which are headed by a person with a job.

- Support the widespread adoption of the Living Wage so that low paid workers receive an adequate income and can afford a minimum, but decent, standard of living.

- Introduce a cost of disability allowance to address poverty and social exclusion of people with a disability.

- Recognise the reality of poverty among migrants and adopt policies to assist this group. In addressing this issue, replace direct provision with a fairer system that ensures adequate allowances are paid to asylum seekers.

- Accept that persistent poverty should be used as the primary indicator of poverty measurement and assist the CSO in allocating sufficient resources to collect this data.

- Move towards introducing a basic income system. No other approach has the capacity to ensure all members of society have sufficient income to live life with dignity.

- Acknowledge the failure to meet repeated policy targets on poverty reduction and commit sufficient resources to achieve credible new targets.