A 5-Pillar Framework for Housing post-COVID-19

Housing in Ireland has been mired in controversy for decades – from tenement slums to planning irregularities, and from substandard housing to the institutionalisation of households in emergency accommodation and Direct Provision. Social Justice Ireland has previously advocated for a 5-Pillar Framework for a new Social Contract. These Pillars are a Vibrant Economy; Decent Services and Infrastructure; Just Taxation; Good Governance; and Sustainability. In this article, we explore what those five Pillars might contain in the context of housing, as an example.

Vibrant Economy

Construction Employment

In Q2 2007, there were 240,000 construction workers in Ireland. Following the crash of 2008, this number fell dramatically and by mid-2012, this number had fallen to just 82,000[1]. Almost half of all workers who lost their jobs between 2007 and 2012 had previously worked in the construction sector, as housing output fell by 90 per cent[2]. By Q1 2020, the number of construction workers had risen to 148,000 – 92,000 less than the 2007 peak. There was a housing crisis before this pandemic. In the ‘before times’ the estimated market demand, that is mortgage approved or cash ready purchasers, was approximately 10,000 from a total real demand of approximately 35,000[3]. We still need affordable, sustainable housing. We cannot, therefore risk losing this vital workforce in the wake of the next recession.

Ensuring a stable construction workforce means changing the way we think about capital projects. Rather than spending hundreds of millions of euro in large-scale capital projects, the benefits of which will not be felt for three years (if then) we should be looking at smaller-scale, socially advantageous construction projects with higher work intensity. Investing in projects such as conversions of over-the-shop units in towns and cities[4]; retrofitting of Local Authority housing and community spaces; provides a stable employment base at a lower cost to the Exchequer than the larger-scale capital projects. Local projects inject much-needed revenue into towns and cities and support regional development. Because they are small scale, there is greater flexibility to scale up or down, depending on available funding; and that funding is more readily available at low interest through EU Green Deal mechanisms. This is a critical issue, and one Social Justice Ireland will return to in due course.

Off-balance sheet investment for social and affordable housing

In December 2017, the CSO reclassified Approved Housing Bodies (AHBs), formerly outside of the general government sector, as being, in whole or in part, part of general government. This decision, affirmed by Eurostat in early 2018, was based on the legislation establishing AHBs; the funding mechanisms used by AHBs and conditions attached; the level of Government control and oversight; the market/non-market nature of AHB rented housing; and the overall policy context. What this decision meant was that the assets and liabilities of these AHBs were to be considered as part of the general government balance sheet. Subsequently any borrowings by these AHBs for the purpose of providing social housing are counted towards the government deficit. Notwithstanding the need to revisit the Stability and Growth pact and the rules concerning budget deficits, as discussed in a recent article, this decision must be appealed if social housing provision is to be scaled up to provide for those in need.

Another area in which an off-balance mechanism could prove useful, is that of providing cost rental housing. As more people are living in private rented accommodation, it is critical that rent costs, which can be over 75 per cent of a tenant’s disposable income, are managed. Social Justice Ireland has previously advocated for affordable rental, through a cost rental model, to be introduced at scale. To do this, we developed a model of financing that is “off balance sheet”, allowing for greater flexibility in design, materials and financing.

Decent Services and Infrastructure

Housing Supply and Affordability

Increasing the supply of housing is not in and of itself going to solve the housing crisis or make housing more affordable. An increase in supply does not necessarily equate to a reduction in prices[5]. Supply must be at the right price points. The wide availability of cheap credit has been more closely linked with affordability and house price increase than supply by commentators both in Ireland[6] and the UK[7]. Robust credit regulation, supply of the right homes in the right location at the right price, and supports to address inequalities inherent in the housing systems which sees greater supply in the commuter belts rather than where housing is actually needed (in cities and, if rural development were to be a priority, in rural towns).

Social Housing

There has been some debate in recent years about “mixed tenure” developments – in fact new developments have, over the past number of years, been required to ensure a tenure mix (for example the Land Development Agency aims to facilitate construction of 10 per cent social, 30 per cent affordable and 60 per cent market price housing). This is arguably the wrong approach if we are to provide adequate accommodation for the most vulnerable households.

There are currently 68,693 households on the social housing waiting lists and in the region of 40,000-50,000 tenancies in receipt of the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) (exact data are not available). The provision of social housing must be prioritised and must be moved from “social housing solutions”, which include private rental subsidies, to social housing provision with homes provided by Local Authorities or properly regulated Approved Housing Bodies. Difficulties experienced by tenants of social housing developments are not a result of the houses, or the people, but of a lack of proper planning, adequate services and opportunities for employment[8]. Once the social structures are in place, any tenure – whether mixed or unitary – could thrive.

The decline in local authority construction, discretionary nature of HAP tenancies, increase in the cost of private rents and the promotion by Government of policies which seek to rely on the private rented sector for the provision of social housing, places low-income households in precarious living situations. It is also a considerable cost to the Exchequer, with Local Authority Budgets for 2020 anticipating an expenditure of €667.4 million for the year[9].

Government should aim to emulate our European peers who perform well in terms of social housing provision and social housing stock. Social Justice Ireland proposes that Government set a target of 20 per cent of all housing stock in Ireland to be social housing and substantial progress to this target should be made in a 5-year programme for Government. Progress updates and reports should be presented annually to the Oireachtas.

Affordable Housing and Low Cost Mortgages

The latest statistics for the 1999 Local Authority Affordable Housing Scheme are from 2016 and show that no affordable homes were provided in 2016 or 2015, 9 were provided in 2014 and none were provided in 2013. Data available from the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, which is available up to Q3 2019, indicate that no affordable housing has been provided under Part V since 2014 when there were 32 units provided[10].

The Rebuilding Ireland Home Loan was introduced in 2018 to provide a low cost mortgage to home buyers who meet the criteria. The full three year allocation for the Rebuilding Ireland home loan scheme was €200 million. In August 2019 an additional €363 million, bringing the total allocation for 2018 and 2019 to €563 million[11], was required. This is one of many examples of Government underbudgeting and overspending. In light of the borrower profile for this loan, that is low income households, reports of rate increases are also concerning[12].

There was a suggestion that Local Authorities might provide low cost mortgages to civil servants[13]. Local Authorities are given targets in respect of the provision of social housing, these targets are insufficient to meet demand and are met to a great extent with the help of the private rented sector. If Local Authorities are to be funded to provide mortgages to civil servants, as suggested, they need to have a definitive plan in place for defaults. The proportion of Local Authority mortgages in arrears has been over 40 per cent since at least 2015, with the exception of Q3 2019, when it was 39 per cent.

Homeless Prevention and Housing First

Social Justice Ireland welcomed the publication of the Housing First National Implementation Plan 2018-2021 in September 2018, however the action to implement it is not keeping pace with the homelessness numbers. The thinking behind Housing First is that immediate permanent housing would be provided to homeless people, followed by the full suite of ‘wraparound’ housing and health supports. This been used successfully in Finland to almost eradicate homelessness in its entirety.

In its policy statement on Family Hubs, IHREC recommended an amendment to section 10 of the Housing Act 1988 to limit the amount of time a family may spend in Family Hubs[14]. A similar regime as in Scotland and something that Social Justice Ireland has been advocating for. This would then allow for the expenditure allocated to Family Hubs to be redirected to support the Housing First programme.

Density

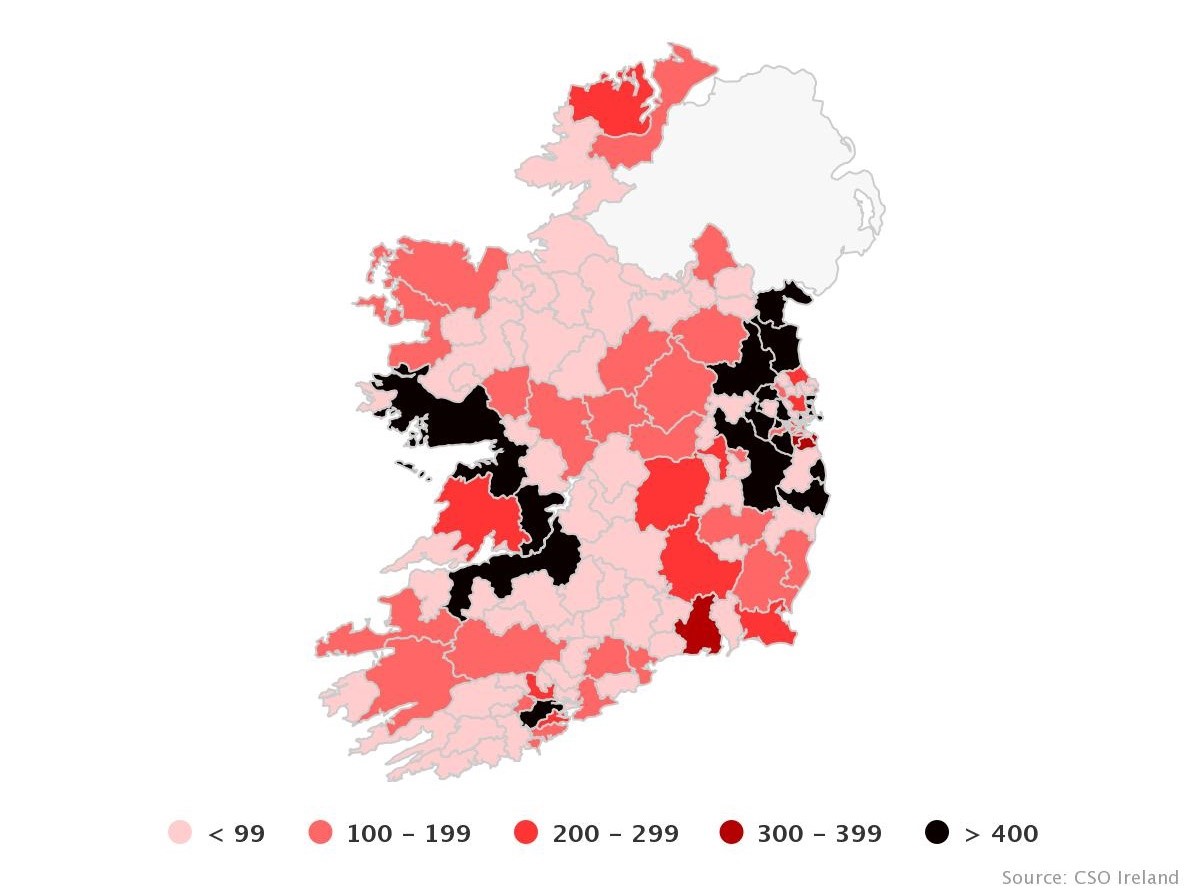

New dwelling completions in 2019 concentrated in Dublin suburbs and commuter belts (which stretch as far as Dundalk), Galway, Limerick and parts of Cork (Figure 1).

Figure 1: New Dwelling Completions by Eircode Routing Key, 2019

Source: CSO, New Dwelling Completions Q4 2019, Figure 3

This ‘urban sprawl’ means longer commuting times and the consequent adverse physical, mental and environmental impacts. Debates on how to address this issue through high-density housing have concentrated on building ‘upwards, not just outwards’[15]. However, high-density does not have to mean high-rise. In its report on Transport-Oriented Development[16], NESC compared urban housing densities in Dublin to those in Amsterdam, Malmo and Copenhagen, and found the suburbs and Ranelagh / Rathmines areas of Dublin to be considerably below the comparators, while the Georgian areas were of similar density, stating (p.17):

High rise is not equivalent to high density. Georgian Dublin achieves fairly high density without being high rise. From a viability perspective, the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government suggests that six storeys are optimal for urban development (ibid.).

Land use is critical to the density debate. A site can have a plot ratio of 100 homes per hectare which, depending on the choice of development could take the form of a high-rise tower with a large communal open space at ground level; a mid-rise building with less communal open space, but some room for amenities, or low rise with individual gardens. The density remains the same, but the use of the land is very different. This concept is developed in some detail in the book Designing High Density Cities edited by Edward Ng[17]. Done well, the benefits of high-density developments can be summarised as follows[18]:

- Living closer encourages more community interaction, and reduces isolation for vulnerable social groups such as young families;

- Compact settlements require less transport and reduce car use, with health and environmental benefits;

- Higher-density development is environmentally beneficial, resulting in lower carbon emissions;

- In rural areas, more compact villages could help stem the decline in rural services, such as shops, post offices and bus services.

Housing development and planning should be about creating liveable communities, with amenities such as playgrounds, green spaces and public transport, and likely environmental and health impacts properly assessed.

Just Taxation

Tax Reliefs

While measures in Budget 2020 to “ensure that an appropriate level of tax is paid on property gains by REITs” were welcome, their introduction came six years after the introduction of the preferential tax treatment of REIT, which was introduced in the Finance Act 2013. All proposed tax structures associated with residential property should be reviewed by the Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service prior to their introduction and subject to annual review by the Department of Finance.

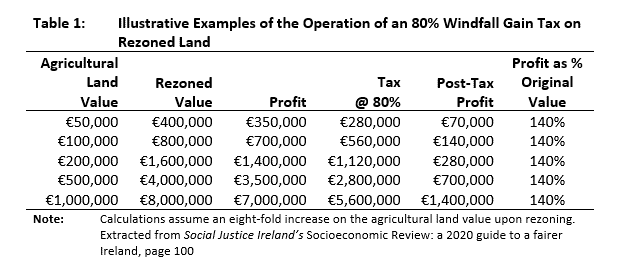

Reinstate the Windfall Gains Tax

For some time, Social Justice Ireland has called for a substantial tax to be imposed on the profits earned from planning decisions which significantly increase the value of land. Re-zonings are made by elected representatives supposedly in the interest of society generally. It is therefore appropriate that a sizeable proportion of the windfall gains they generate should be made available to Local Authorities and used to address the ongoing housing problems they face. In this regard, Social Justice Ireland welcomed the decision to put such a tax in place in 2010 and strongly condemned its removal as part of Budget 2015. Its removal has been one of the most retrograde policy initiatives in recent years.

Some illustrative examples of the operation of an 80% windfall gain tax on rezoned land were published in our latest socioeconomic review (Table 1) [19]:

Site Value Tax

Site Value Tax (SVT) is a charge on the value of land (i.e. the value of the site), not taking into account any of the physical capital built on the land. Another way of saying this is that it is a charge on the ‘unimproved value of the land’. In this way, the charge is related to the value of the location. It is calculated as a percentage of the value of the site.

SVT is the fairest form of property tax. It is also simpler than most people first imagine. The tax is charged on the land, without taking account of any of the landowners activities. It is levied from when the site entered into economic activity and means that the public investment in surrounding infrastructure, maintenance of environmental assets and public amenities, paid for by all tax payers, is recouped through the taxation system. The arguments in favour of SVT are numerous and are outlined in some detail in this article. We also produced a podcast on SVT this week, which can be accessed here.

SVT is a fairer, more sustainable tax than Local Property Taxes and should be brought in to replace the LPT system at Local Authority level.

Good Governance

Regulations

The Strategic Housing Development (SHD) was introduced in 2017 to fast track planning applications and avoid unnecessary delays for developments of 100 residential units or more (and 200 or more student bed places). Concerns have been expressed by the Irish Planning Institute[20], among others, that the SHD contravenes the Aarhus Convention in that objections may only be raised on application to the High Court which can be prohibitively expensive; that it takes too much of the planning process away from Local Government and elected officials; and that it results in poor urban planning.

Reductions in building standards for the buy to let market – small units, lack of cross-ventilation, no balconies – have been exposed by the current pandemic as the health hazards they are. Building standards must be refocused to have public health and sustainable living at the core of housing development, rather than profit.

Tenant Protections

When it comes to landlord and tenant rights in Ireland, these rights are weighed heavily in favour of the landlord whose Constitutionally-protected property rights take precedence over the human right of the tenant to live in adequate, safe and sustainable accommodation. The rate of Local Authority inspections of private rented property has been consistently low, while the rate of non-compliance with basic health and safety regulations among those properties that are inspected has been high.

In recent years, Government has moved to provide greater protections for tenants, with the introduction of Rent Pressure Zone legislation and amendments to the Residential Tenancies Act, 2004 providing for longer notice periods and increased obligations on landlords wishing to serve a notice to quit. For social housing tenants accommodated through the private rented sector, changes to the equality legislation also saw a prohibition on discrimination by landlords of tenants in receipt of HAP. However, even if they were properly enforced (which they are not) these changes do not go far enough to address the imbalance of power between the landlord and their tenant.

Regulation of the private rented market must reflect its increasing importance as a housing provider, as reliance on the private rented sector increases across all socio-demographic profiles. Social housing tenants, who are particularly vulnerable to the exigencies of the market, must be protected within this sector until such time as real social housing has been sufficiently delivered to scale. This means that anti-discrimination legislation must be enforced and that HAP payments should reflect market rents so that low income households are not choosing between rent top-ups and other essentials such as food, light and heat.

The deposit protection scheme, on the statute books since 2015, must be commenced to protect the sizable sums of money being asked of tenants in respect of security deposits. The rate of rent inspections must be increased to ensure that properties are safe and Social Justice Ireland supports the call by Threshold and others for the introduction of an NCT-style certification to ensure that rental properties are of a tenantable standard.

If, as seems likely, the private rented sector is to be a significant feature of the Irish housing system into the future, then we must future-proof tenancies. The introduction and regulation of long-term tenancies would secure accommodation for tenants as they age to ensure that they have an adequate place to live post-retirement in the event of a reduction in income. The design of these tenancies could account for the amortisation of some of the landlord costs associated with renting over time to allow for an appropriate rent-setting system.

A Right to Housing

The right to housing, at its most basic level, is the right of everyone to be adequately accommodated. This does not mean that everyone has a free house, or that everyone even owns a house, but that a person’s basic need for shelter has the same Constitutional protection as the property rights of landowners. Various homelessness and housing organisations have campaigned for this right to be enshrined in the Constitution, with a groundswell of public support at national protests calling for a Referendum.

In May 2016, when there were just 3,930 homeless adults and 1,881 homeless children accessing emergency accommodation (compared to 6,552 adults and 3,355 children in March 2020), the Mercy Law Centre published a report on the Right to Housing in Ireland[21]. This report referred to European countries such as Belgium, Finland, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden, that have enshrined the right to housing in their Constitutions, and to Austria, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the UK that have enacted the right by legislation. The operation of this right has not damaged the rights of landowners in these countries, but it has required the courts to consider a person’s accommodation needs in the event of a threat of homelessness. A right to housing in the Irish Constitution would likely not mean an end to homelessness in itself, but would recognise the importance of having a home to our basic human dignity, and look to protect that dignity with the fullness of the law.

Sustainability

Retrofitting

An estimated 230,650 homes have BER certificates of F or G, the least energy efficient housing. These homes are more likely to be cold or damp and, consequently, have much greater heating costs (over 585,000 people in Ireland live in a dwelling with a leaking roof, damp walls, floors or foundation, or rot in window frames or floor[22]). These are more likely to be poorer households or households headed by older people. They are also more likely to use coal, peat and other fossil fuels in their heating[23]. The recent confusion regarding the status of the SEAI Deep Retrofit Scheme Pilot is concerning. However, even with this in place, the households most likely to need it were least able to avail of it, finding the upfront costs prohibitive.

Instead, investment in a retrofitting programme could be modelled on the one used in the Netherlands and part of the UK, whereby subsidised costs are spread out and paid through energy bills, making it easier for low income households to participate.

This not only provides environmental benefits but contributes to the sustainability of employment in the construction sector, as referred earlier. It also has knock-on benefits for the whole economy, as detailed in the recent ESRI report which calls for infrastructural projects which prioritise sustainability and climate goals[24].

Sustainable Design

Retrofitting existing properties is key to moving towards more environmentally, and socially, sustainable housing. However new housing, whether one off or scheme builds, must be designed to the highest sustainability standards. Employing circular economy principles and using more sustainable materials, such as green concrete[25], can contribute to more passive, environmentally friendly buildings.

Housing for the Lifecycle

Housing planning and development must take a whole of life approach, based on the needs of households throughout the lifecycle. If housing policy was based on sustaining communities, more options would be created to provide for family homes; student and professional accommodation; downsizing opportunities for older people who may wish to move from a larger family home once their families have moved on; and supported accommodation for people with additional needs. Building sustainable communities that people want to live in, decrease outward migration and can help to revitalise rural towns and villages which suffered the effects of the last recession as local services and retail closed and social isolation became a prevalent feature.

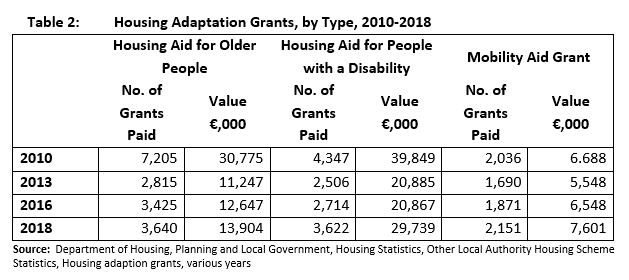

In addition, for older people and people with disabilities in existing inadequate accommodation, the cuts to Housing Adaptation Grants have been detrimental. Housing Adaptation Grants is the collective term given to the three grants: Housing Aid for Older People, Housing Aid for People with a Disability and Mobility Aid Grant. These grants are provided to eligible people to modify their own homes, allowing them to live at home, within their communities, for longer. Given the large proportion of people living with a disability who own their own homes, the Housing Adaptation Grants are especially important. In 2010, a total of €77.3 million was paid in respect of 13,588 grants. These grants were subject to cuts during the austerity years, and in 2013 reached their lowest point in the decade, with €37.7 million paid in respect of 7,011 grants, less than half 2010 levels. Building on moderate increases since 2015, the total amount paid in respect of these grants in 2018 was €51.2 million in respect of 9,413 grants. An improvement on 2013, but still just two-thirds of 2010 levels (Table 2).

Delays in accessing the necessary Occupational Therapists to certify a need for home modifications means that people living with disabilities may be at additional risk in their homes due to lack of necessary works.

Conclusion

Housing was a serious issue before the current pandemic. We had:

- almost 69,000 households on the social housing waiting list and tens of thousands more in precarious private rented tenancies;

- house prices and rents were increasingly unaffordable;

- 10,000 people were accessing emergency homelessness accommodation;

- poor standards in buildings and rented properties;

- approximately 6,000 people warehoused in Direct Provision centres;

- substandard Traveller accommodation and a lack of real action on the part of Local Authorities to address this;

- inadequate housing and insufficient housing grants to cater for older people and people with disabilities and

- a lack of suitable safe spaces for victims of domestic abuse.

Privatisation and financialisation dominated housing policies, with vulnerable people left out in the cold. Sometimes literally. We need to rethink our housing system in the context of a new Social Contract in the interest of society, the economy and the environment and to take an integrated approach to its development.

[1] CSO Labour Force Survey, Statbank [QLF03]

[2]https://www.centralbank.ie/docs/default-source/publications/quarterly-bulletins/quarterly-bulletin-signed-articles/where-are-ireland-s-construction-workers-(conefrey-and-mcindoe-calder).pdf?sfvrsn=4

[3]https://www.broadsheet.ie/2020/01/21/its-not-possible-to-make-housing-mo...

[4] Hegarty, O. (2018): Submission to the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Housing, Planning, Community and Local Government on the Vacant Housing Refurbishment Bill 2017

[5] Szumilo, Nikodem (2018) Housing affordability: is new local supply the key? Environment and Planning, London School of Economics and Political Science: London

[6] Lyons, R. (2017): “Housing Market: Supply, Pricing and Servicing Issues”. In John O’Hagan and Francis O’Toole (eds), The Economy of Ireland – Policy & Performance (13th edition). London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017

[7] Mulheirn, I. (2019): Tackling the UK housing crisis: is supply the answer?, UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence,

[8] Fahey, T. (1999): Social Housing in Ireland: A study of success, failure and lessons learned, Oak Tree Press: Dublin.

[9]www.localauthorityfinances.com

[10] Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, Local Authority Housing Scheme Statistics, Affordable housing and Part V statistics

[11]https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2019-10-10/269/

[12]https://www.thejournal.ie/rebuilding-ireland-home-loan-4-4969402-Jan2020/

[13]https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/dermot-desmond-everyone-has-a-right-t...

[14]https://www.ihrec.ie/app/uploads/2017/07/The-provision-of-emergency-acco...

[15]https://www.irishtimes.com/news/environment/cultural-change-needed-for-communities-to-accept-high-density-housing-1.4041872; https://www.rte.ie/news/business/2020/0212/1114892-high-rise-development-needed-to-solve-housing-crisis/

[16]http://files.nesc.ie/nesc_reports/en/148_TOD.pdf

[17] Ng.E (2009): Designing High-Density Cities: For Social and Environmental Sustainability, Routledge

[18] Willis, (2008): extracted from Designing High Density Cities: For Social and Environmental Sustainability, citation as above.

[19]Social Justice Ireland (2020): Socioeconomic Review: Social Justice Matters: 2020 guide to a fairer Irish society, Dublin.

[20]https://www.ipi.ie/sites/default/files/accordion-files/final_shd_submiss...

[21]https://mercylaw.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/MLRC-Report-on-Right-to-H...

[22] Eurostat Database [ilc_mdho01]

[23] CSO Domestic Building Energy Ratings Q1 2020

[24]https://www.esri.ie/system/files/publications/QECSUM2020.pdf

[25]https://passivehouseplus.ie/news/product-news/green-concrete-breakthroug...