Assessing the Adequacy of Ireland’s Total Tax-Take

The need for a wider tax base is a lesson painfully learnt by Ireland during the last economic crisis. A disastrous combination of a naïve housing policy, a failed regulatory system, and foolish fiscal policy and economic planning caused a collapse in exchequer revenues. It is only through a strategic and determined effort to reform Ireland’s taxation system that these mistakes can avoided in the future. The narrowness of the Irish tax base resulted in almost 25 per cent of tax revenues disappearing, plunging the exchequer and the country into a series of fiscal policy crises. As shown in Table 1, tax revenues collapsed from over €63bn in 2007 to a low of €47.4bn in 2010; it has since increased exceeding 2007 levels in 2016 and reaching just over €80bn in 2019. This recovery, while both significant and remarkable, has also been fuelled by short-term windfall revenue from some multi-national companies.

Table 1: The Changing Nature of Ireland’s Tax Revenue (€m) | |||||||

2007 | 2008 | 2010 | 2015 | 2019 | |||

Direct Taxes | 26,087 | 22,964 | 19,569 | 27,863 | 36,627 | ||

Indirect Taxes | 25,854 | 22,557 | 18,076 | 22,486 | 27,467 | ||

Capital Taxes | 432 | 368 | 245 | 401 | 531 | ||

Social Contributions | 10,723 | 11,010 | 9,511 | 12,322 | 15,847 | ||

Total Taxation | 63,096 | 56,899 | 47,401 | 63,071 | 80,471 | ||

% GDP | 32.0% | 30.3% | 28.3% | 24.0% | 22.6% | ||

% GNP | 37.3% | 35.4% | 34.0% | 31.4% | 29.3% | ||

% GNI | 37.0% | 35.0% | 33.7% | 31.2% | 29.2% | ||

% GNI* | 38.1% | 36.3% | 36.8% | 38.8% | 37.7% | ||

% GNDI | 37.6% | 35.6% | 34.4% | 31.7% | 29.6% | ||

Source: | CSO online database (GFA03 and N1703) and CSO Gov. Finance Statistics (2019). | ||||||

Note: | Total taxation expressed as a percentage of published CSO national income figures at current prices. GDNI is Gross National Disposable Income and represents the total income available to the nation for either consumption or saving. | ||||||

Future taxation needs

Government decisions to raise or reduce overall taxation revenue needs to be linked to the demands on its resources. These demands depend on what Government is required to address or decides to pursue. The effects of the economic crisis a decade ago, and the way it was handled, also carry significant implications for our future taxation needs. The rapid increase in our national debt, driven by the need to borrow both to replace disappearing taxation revenues and to fund emergency ‘investments’ in the failing commercial banks, has increased the on-going annual costs associated with servicing the national debt. Similarly, the need for the state to rescue or support so many aspects of our economy and society during the Coivd-19 pandemic has triggered large scale borrowing and future liabilities to both service and repay this debt.

Ireland’s national debt increased from a level of 24 per cent of GDP in 2007 - low by international standards - to peak at 119.9 per cent of GDP in 2013. Documents from the Department of Finance, to accompany Budget 2021, indicate that debt levels fell to 57 per cent of GDP (€204 billion) in 2019 but will rise to at least 66.6 per cent of GDP (€240 billion) during 2021. The unpredictable nature of the pandemic, and the likely challenging recovery from it, suggest that the national debt may climb further in the immediate years ahead. The large revision in GDP for 2015 has had a significant effect on this debt indicator. Despite favourable lending rates and payback terms, there remains a recurring cost to service this debt – costs which have to be financed by current taxation revenues. The estimated debt servicing cost for 2021 is €4.5bn.

These new future taxation needs are in addition to those that already exist for funding local government, repairing and modernising our water infrastructure, paying for the health and pension needs of an ageing population, paying EU contributions and funding any pollution reducing environmental initiatives that are required by European and International agreements. Collectively, they mean that Ireland’s overall level of taxation will have to rise significantly in the years to come – a reality Irish society and the political system need to begin to seriously address.

As an organisation that has highlighted the obvious implications of these long-terms trends for some time, Social Justice Ireland welcomes the development over the past few years where the Government has published a section of the April Stability Programme Update (SPU) focused on the long-term sustainability of public finances.

Research by Bennett et al, the OECD and the ESRI have all provided some insight into future exchequer demands associated with healthcare and pensions in Ireland in the decades to come. The Department of Finance has used the European Commission 2018Ageing Report as the basis for its assumptions from 2020-2070 which are summarised in table 2. Over the period the report anticipates an increase in the older population (65 years +) from approximately 712,000 people in 2020 to 1.2m in 2040 and to a peak of 1.49m in 2060. Over the same period, the proportion of those of working age will decline as a percentage of the population and the old-age dependency ratio will increase from almost five people of working age for every older person today to less than three for every older person from 2040 onwards. While these increases imply a range of necessary policy initiatives in the decades to come, there is an inevitability that an overall higher level of taxation will have to be collected.

Table 2: Projected Age-Related Expenditure, 2020-2070

Expenditure areas | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 | 2070 | |||

% GDP | |||||||||

Gross Public Pensions | 5.1 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.6 | |||

of which: | |||||||||

Social protection pensions | 3.8 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.0 | |||

Public service pensions | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | |||

Health care | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.1 | |||

Long-term care | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.3 | |||

Education | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | |||

Unemployment benefits | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |||

Total age-related spending | 15.1 | 16.6 | 17.8 | 19.6 | 19.9 | 19.2 | |||

% GNI* | |||||||||

Gross Public Pensions | 8.0 | 9.1 | 10.5 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 10.3 | |||

of which: | |||||||||

Social protection pensions | 6.0 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 9.4 | |||

Public service pensions | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 1.0 | |||

Health care | 6.6 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.2 | |||

Long-term care | 2.2 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 5.1 | |||

Education | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.2 | |||

Unemployment benefits | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | |||

Total age-related spending | 23.6 | 26.0 | 28.0 | 30.4 | 31.2 | 30.3 | |||

Source: | Department of Finance. | ||||||||

How much should Ireland collect in taxation?

Social Justice Ireland believes that, over the period ahead, policy should focus on increasing Ireland’s tax-take. Previous benchmarks, set relative to the overall proportion of national income collected in taxation, have become redundant following recent revisions to Ireland’s GDP and GNP levels as a result of the tax-minimising operations of a small number of large multinational firms.[1] Consequently, an alternative benchmark is required.

We have proposed a new tax take target set on a per-capita basis; an approach which minimises some of the distortionary effects that have emerged in recent years. Our target is calculated using CSO population data, ESRI population projections, and CSO and Department of Finance data on recent and future nominal overall taxation levels. The target is as follows:

Ireland’s overall level of taxation should reach a level equivalent to €15,000 per capita in 2017 terms. This target should increase each year in line with growth in GNI*.

Table 3 compares our target to the Budget 2021 expectations of the Department of Finance. We also calculate the overall tax gap for the economy; the difference between the level of taxation that is proposed to be collected and that which would be collected if the Social Justice Ireland target was achieved. As part of our calculations, we have adjusted the expected Department of Finance tax take to remove an estimate of the windfall short-term corporate taxes the state is currently receiving; revenues which are likely to go elsewhere as the broader OECD and EU reforms of corporate taxation regimes advances. We have chosen a conservative figure of €4.5billion to make this adjustment.

In 2021 the overall tax gap is €5.4 billion and the average gap over the period 2019-2021 is €6 billion per annum.

Table 3: | Ireland’s Tax Gap, 2019-2021 |

2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

Tax-take € per capita | |||

Budget 2021 projection | €15,580 | €14,683 | €15,333 |

Social Justice Ireland target | €16,642 | €16,160 | €16,418 |

Difference | €1,062 | €1,477 | €1,085 |

Overall Tax-take €m | |||

Budget 2021 projection# | €76,679m | €73,083m | €76,931m |

Social Justice Ireland target | €81,905m | €80,433m | €82,374m |

Tax Gap | €5,225m | €7,349m | €5,443m |

Notes: Calculated from Department of Finance, CSO population data and ESRI population projections (Morgenroth, 2018:48). GNI* is assumed to move in line with GNP – as per Department of Finance (2017:49). The Tax Gap is calculated as the difference between the Department of Finance projected tax take and that which would be collected if total tax receipts were equal to the Social Justice Ireland target. # The tax take has been adjusted to remove €4.5b as a conservative estimate of short-term tax revenues from MNCs; targets are calculated post its removal.

Increasing the overall tax take to this level would require a number of changes to the tax base and the current structure of the Irish taxation system, reforms which we address in the next section of this chapter. Increasing the overall taxation revenue to meet this new target would represent a small overall increase in taxation levels and one which is unlikely to have any significant negative impact on the economy.

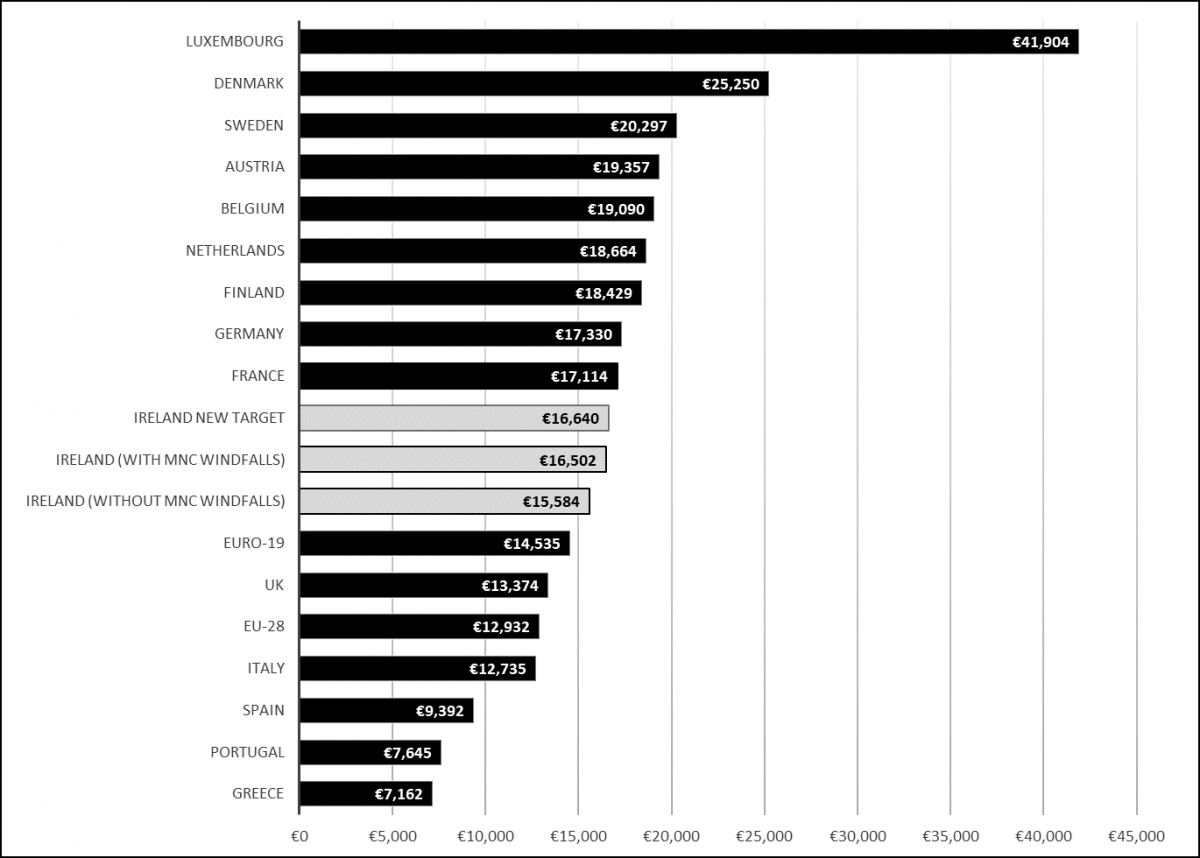

Chart 1: Per-Capita Tax Take in EU-15 States, 2019

Source: Calculated from Eurostat online database and see notes to Table 3.

Chart 1 compares the target to the situation in other comparable high-income EU states (the EU-15) using the latest Eurostat data which is for 2019. The updated Social Justice Ireland tax target for 2019 is €16,640 per capita. In that year Ireland’s per capita tax figure was €16,502 when the tax windfalls of multi-national corporations (MNCs) are included but about €1,000 below the target when these transitory revenue sources are excluded. The Social Justice Ireland tax target does not alter Ireland’s relative position or alter its status as among the lowest taxed economies in Europe. However, reaching that level would provide a lot more recurring revenue for the state to invest in public services and improved living standards for all. As a policy objective, Ireland can remain a low-tax economy, but it should not be incapable of adequately supporting the economic, social and infrastructural requirements necessary to support our society and complete our convergence with the rest of Europe.

[1] For many years Social Justice Ireland proposed that the overall level of taxation should reach 34.9 per cent of GDP.