COVID-19 and the Irish Healthcare System

Current pandemic exacerbating existing problems in Ireland’s health care system

COVID-19 is placing unprecedented pressure on our healthcare system. The emergency measures implemented to date are welcome and necessary. However in the medium and long term we must address the issues of bed capacity, lack of step down care facilities and the need to broaden access to community care so that our acute hospital system is better placed to deal with any future shock.

Underlying problems

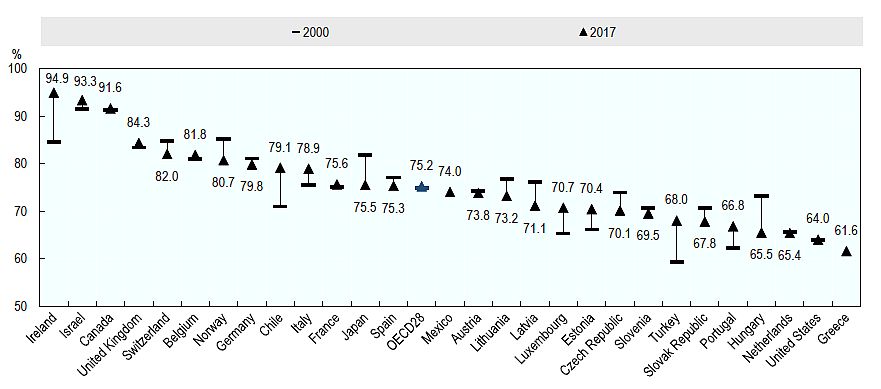

Before the COVID-19 pandemic ever reached these shores Irish hospitals were already working near full capacity. The occupancy rate for acute care beds is among the highest in OECD countries, and while having a high utilisation rate of hospital beds can be a sign of hospital efficiency, it can also mean that too many patients are treated at the secondary care level.

Even though Ireland spends more per capita on Health than the OECD average (health spending is almost 25 per cent higher), the number of beds per 1,000 population is considerably less than the OECD average, and our hospital bed occupancy rate reaches almost 95 per cent (see chart 1). This is about 20 percentage points higher than the OECD average (which was 75.2 per cent)[1] and the highest in the EU 28. In its report on the Irish Healthcare system in 2019 the OECD found it to be hospital-centric, with significant capacity constraints in primary and secondary care and concluded that the current health infrastructure is simply not adequate for current demand and unable to cope with the projected increases due to population ageing. And that was before a global pandemic.

Chart 1: Occupancy Rate of Curative (acute) Care Beds, 2000 and 2017 (or nearest year)

One of the things that contributes to this situation is the inability to discharge people, often older patients, due to problems accessing support in the community and step-down facilities, nursing homes and other forms of support. The problems associated with our high bed occupancy rates are associated with a persistent failure to invest properly in areas such as primary care, community care and step-down facilities.

A recent ESRI report highlights unmet need for formal home support, finding that Ireland provides formal care to only 24 per cent of those needing it and that (among the different groups examined) 38 per cent of people over 65 have unmet needs for care, as do 34 per cent of disabled adults[2]. The HSE estimated in 2017 that increasing availability of rehabilitation beds would potentially free up 12 per cent of delayed discharge beds[3]. In 2019 the OECD came to a similar conclusion noting that the high rate of delayed discharges in Ireland contributes to high hospital bed occupancy rates. Hospital bed occupancy rates could be reduced if post-discharge planning and care arrangements for the elderly were improved and if access to primary care and community care was improved.

At the end of September 2019, there were 724 delayed discharges recorded by the HSE of which 137 were waiting to go home, 454 were awaiting nursing home care and 133 complex patients awaiting bespoke supports[4]. This represents an increase of 19.5 per cent on September 2018, and is 31.6 per cent above the maximum target of 550. There were a further 7,252 people waiting on funding for home support. Hospital bed occupancy rates could be reduced if post-discharge planning and care arrangements for the elderly were improved and if access to primary care and community care was improved.

The impact of COVID-19

The failure to properly invest in primary care was having detrimental impacts on the Irish healthcare system long before the COVID-19 pandemic. But this lack of investment now leaves our system painfully exposed.

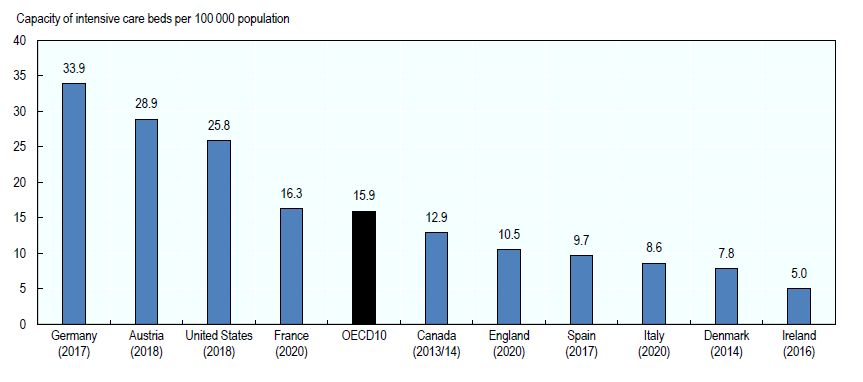

In a policy briefing on healthcare system responses to COVID-19, the OECD emphasises that the experience in China and Italy has highlighted the critical need to ensure adequate capacity of hospital beds in general and intensive care. The report finds that given the characteristics of the treatment required for the most severe COVID-19 patients, the most important bottlenecks in hospital capacity are taking place in intensive care beds. A preliminary analysis of the most recent publicly available data suggests that, across ten OECD countries, the variation in capacity is six-fold, ranging from a high of 33.9 critical beds per 100,000 population to a low of 5.0 beds per 100,000 (see chart 2). Ireland is at the low end with just 5.0 beds per 100,000 of population.

Chart 2: Capacity of intensive care beds in selected OECD countries, 2020 (or nearest year)

High occupancy rates of acute care beds are symptomatic of a health system under pressure that has limited capacity to handle an unexpected surge of patients requiring immediate hospitalisation. Ireland has almost no capacity when it comes to this issue with a bed occupancy rate of 95 per cent (see chart 1 above). This problem within the Irish healthcare system has been highlighted for a number of years and is primarily as a result of a lack of an integrated primary and community care structure. Ireland remains the only Western European country without universal coverage for primary care.

Medium to long term policy goals

The correct policy response in the Irish context in the medium to long-term, once this crisis is over, is to focus on developing our primary care and community care infrastructure so that acute care beds can be made available quickly in times of extreme pressure such as we are experiencing at present.

For Ireland, a key medium to long-term policy goal must be to develop Ireland’s healthcare system so that it provides universal coverage for primary care. This requires investment in community care, primary care and social care. It requires a rebalancing from the current system of reliance on hospital care with resources being diverted to primary care and to implementing Sláintecare.

As stated, Ireland remains the only Western European country without universal coverage for primary care. Unfortunately the Sláintecare measures taken so far do not commit to providing universal health coverage by legislating for an entitlement to care.

Social Justice Ireland believes that access to healthcare based on need, not income, should remain an important aim for Ireland’s healthcare system. We welcomed, in particular, the Sláintecare recognition that Ireland’s health system should be built on the solid foundations of primary care and social care. However, the required capital allocation of €500 million per year for the first six years to support the infrastructure to implement Sláintecare has not been made since the programme received cross-party support. In order to deliver the modern, responsive, integrated public health system that the report envisages it is vital that the necessary investment is made available.

Since the formation of the HSE in 2005, healthcare has consistently accounted for approximately a quarter of all voted expenditure. In recent Budgets, Social Justice Ireland has highlighted issues with the allocation to Health as being insufficient to address new measures and existing commitments, unlikely to address waiting lists, and inadequate to address and plan for population ageing. Thus, an open and transparent debate on the funding of healthcare services and on the optimal delivery model is also needed. This debate must acknowledge the enormous financial expenditure on healthcare and the issues we raise above about healthcare expenditure, including the fact that, in international comparison, Ireland's per capita expenditure on healthcare is relatively high, despite a relatively young population.

Once the worst of the COVID-19 crisis has passed, healthcare policy in Ireland should focus on the following:

- Ensuring that announced budgetary allocations are valid, realistic and transparent and that they take existing commitments into account.

- Increasing the availability and quality of Primary Care and Social Care services.

- Creating additional respite care and long-stay care facilities for older people and people with disabilities and provide capital investment to build additional community nursing facilities. Implement all aspects of the dementia strategy.

- Working towards full universal healthcare for all. Ensure new system structures are fit for purpose and publish detailed evidence of how new decisions taken will meet healthcare goals.

- Enhancing the process of planning and investment so that the healthcare system can cope with the increase and diversity in population and the ageing of the population projected for the next few decades.

- Ensuring that structural and systematic reform of the health system reflects key principles aimed at achieving high performance, person-centred quality of care and value for money in the health service.

Conclusion

As outlined above community services are not fully meeting growing demands associated with population change reflected in the inappropriate levels of admission to, and delayed discharges from, acute hospitals. With increases in the population, especially amongst older people, the acute hospital system, which is already under pressure, will be unable to operate effectively unless there is a greater shift towards primary and community services as a principal means of meeting patient needs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed how reliant the Irish public health service on the acute hospital system to deliver care. Concerns regarding our high bed occupancy rate and our underdeveloped primary care and social care infrastructure, expressed over many years went unheeded. These concerns must guide health policy once the worst of the health impacts of COVID-19 have passes. If we are to deliver a healthcare system to meet our needs, today, and in the coming decades – one that is well placed to deal with any future shocks - we must invest in our primary and community care infrastructure and fully implement Sláintecare.

Courageous political leadership is needed to implement a significant change in the healthcare model – and this requires an open debate about the choices involved and the intended benefits of a universal system that focuses on primary and community care.

People should be assured of the required treatment and care in their times of illness or vulnerability. The standard of care is dependent to a great degree on the resources made available, which in turn are dependent on the expectations of society. The obligation to provide healthcare as a social right rests on all people. In a democratic society this obligation is transferred through the taxation and insurance systems to government and other bodies that assume or contract this responsibility. How we deliver a healthcare system that can meet our current and future needs and cope with any future shocks will be an integral part of a new social contract.

[1]https://www.oecd.org/ireland/ireland-country-health-profile-2019-2393fd0...

[2]https://www.esri.ie/publications/access-to-childcare-and-home-care-servi...

[3]https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/news/newsfeatures/planning-for-health/

[4]https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/performancereports/july-to-...