COVID-19 highlights issue of Job Precarity

An estimated 492,000 workers in Ireland may lose thier jobs due to the coronavirus, COVID-19. The sectors most affected by these job losses are those in which it is difficult to impossible to work from home and, due to necessary restrictions in the interest of public safety, must now close. These jobs concentrate in the retail, hospitality, recreation, non-essential manufacturing and construction sectors. Analysis by the Parliamentary Budget Office published last week [1] indicated that these workers are, overall, more likely to be male (notwithstanding some of the more female-dominated retail sectors being included in this list) and younger than the total working population (approximately 60 per cent of workers in these affected sectors are male, compared to 53 per cent in the total workforce; 19 per cent of workers in these sectors are younger than 25, compared to just 11 per cent in the total workforce). And, of course, there will be knock-on effects on sectors not directly being asked to close as they see a reduction in revenues due to lack of spending. These knock-on effects will impact both local and national businesses as well as national and international supply chains.

While the restrictions are necessary to save lives, and many job losses may be temporary, this crisis has demonstrated the precarity inherent in certain economic sectors.

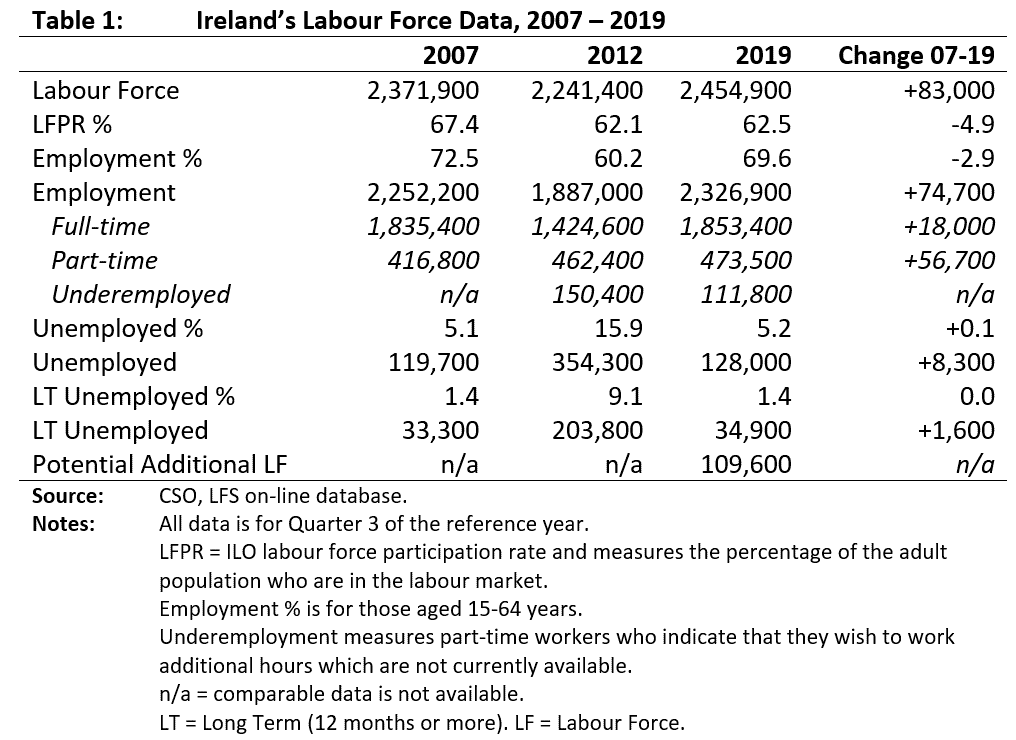

The number of people employed prior to the current crisis was higher than it ever has been. However, because of the population increase, since 2007 the proportion of the labour force who were at work – the employment rate – has fallen by almost three percentage points. Considerably more jobs were created as part-time positions (+56,700 since 2007) than full-time (+18,000). Within those part-time employed it is worth focusing on those who are underemployed, that is working part-time but at less hours than they are willing to work. By the third quarter of 2019 the numbers underemployed stood at 111,800 people, 4.6 per cent of the total labour force and about one-quarter of all part-time employees (Table 1).

These figures suggest the emergence of a greater number of workers in precarious employment situations. While there is no agreed definition of precarious work, it generally covers unpredictable work patterns and ill-defined hours coupled with instances of in-work poverty. As of Q4 2019, 116,700 workers were on variable hours contracts, which include persons for whom no usual hours of work are available[2]. A recent report from the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI)[3] found that a “substantial proportion” of recent employment growth came from sectors with “above-average risk of precariousness” (42%). The authors of the report also found that the share of temporary workers on part-time contracts had increased; the proportion of those reporting inability to find a permanent job was three times the pre-crash rate; and the proportion of temporary employees on contracts of less than a year had increased by over 50 per cent in the past decade.

The growth in the number of individuals with less work hours than ideal, as well as those with persistent uncertainties concerning the number and times of hours required for work, is a major labour market challenge. Aside from the impact this has on the well-being of individuals and their families, it also impacts on their financial situation and adds to the challenges faced by the working-poor. There are also impacts on the state, given that the Working Family Payment (formerly known as Family Income Supplement (FIS)) and the structure of jobseeker payments tend to lead to Government subsidising these families’ incomes, and indirectly subsidising some employers who create persistent precarious employment patterns for their workers.

On the 24th March 2020, the Government announced an increased COVID-19 Unemployment Payment and COVID-19 Illness Benefit of €350 per week, acknowledging the inadequacy of standard rate social welfare payments (€203 per week) as a living wage. It also announced a wage subsidy scheme for businesses that can demonstrate a 25 per cent decline in turnover and an inability to pay wages as a result of significant disruption caused by this crisis. This subsidy will cover 70 per cent of an employee's net pay up to a maximum of €410 per week. Analysis of earnings in sectors affected by job losses as a result of COVID-19, conducted by the Parliamentary Budget Office (reference as above), show that they are generally lower than the national average. The COVID-19 unemployment and illness payments will therefore cover a significant proportion of lost earnings for the 12 week period it is in place, except in construction and manufacturing where it accounts for 56 per cent and 52 per cent respectively. If, rather than laying staff off, businesses in these sectors avail of the subsidy, this should cover 70 per cent of wages for lower income sectors, as staff in these sectors would earn less than the maximum €38,000 per annum, but again would cover a lower proportion of wages in the construction and manufacturing sectors.

There are clear and pervasive income inequalities, and issues with precarity, in Ireland. Once we get through the current crisis, the Government must adopt substantial measures to address and eliminate these problems, including the development and adoption of a Living Wage.

The establishment of the Low Pay Commission is a welcome development. It is important that this group provides credible solutions to these labour market challenges and that such proposals are implemented.

Need to Recognise All Work

A major question raised by the current crisis concerns assumptions underpinning culture and policymaking in the area of work. The priority given to paid employment over other forms of work, and to higher-paid employment over lower-paid service work, are just some such assumptions. Most people recognise that a person can be working very hard outside a conventionally accepted “job”. Much of the work carried out in the community and in the voluntary sector comes under this heading. So too does much of the work done in the home.

Community and Voluntary organisations have a long history of providing services and infrastructure at local and national level. They are engaged in most, if not all, areas of Irish society. They provide huge resources in energy, personnel, finance and commitment that, were it to be sourced on the open market, would come at considerable cost to the State. They have developed flexible approaches and collaborative practices that are responsive and effective in meeting the needs of diverse target groups, particularly at a time of crisis.

The need to recognise voluntary work has been acknowledged in the Government White Paper, Supporting Voluntary Activity[4]. This report was prepared to mark the UN International Year of the Volunteer 2001 by Government and representatives of numerous voluntary organisations in Ireland. The report made a series of recommendations to assist in the future development and recognition of voluntary activity throughout Ireland. The draft Volunteering Strategy 2020-2025[5], currently under review with the Department of Rural and Community Development, also acknowledges this.

There are an estimated 189,000 employees in registered charitable organisations in Ireland. Over half of all registered charities have between one and 20 volunteers, with three per cent having 250 or more. It is estimated that the value of this volunteering work, using the minimum wage, is €648.8 million per year (this increases to €1.5 billion when using the average income)[6]. It is important to note, however, that this report is based on those charities that are required to register with the Charities Regulator, which accounts for approximately 300,536 volunteers. CSO data puts the number of volunteers at nearer to one million, when sporting, human rights, religious and political organisations are included[7].

This work has proven to be invaluable in the context of the current pandemic. Community and Voluntary organisations, carers and informal voluntary networks have come together to support the most vulnerable in society. Social Justice Ireland believes that government should recognise, in a more formal way, all forms of work. We believe that everyone has a right to work, to contribute to his or her own development and that of the community and wider society. We also believe that policymaking in this area should not be exclusively focused on job creation. Policy should recognise that work and a job are not always the same thing and should be compensated accordingly.

[1] https://data.oireachtas.ie/ie/oireachtas/parliamentaryBudgetOffice/2020/...

[2] Central Statistics Office, Labour Force Survey (LFS) Time Series, Table S1

[3] https://www.nerinstitute.net/sites/default/files/research/2019/precariou...

[4] https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/eb9f99-white-paper-supporting-voluntar...

[5] https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/44992/9bb2e75e55e1451...

[6] https://www.charitiesregulator.ie/media/1564/indecon-social-and-economic...

[7] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/q-vwb/qnhsvolunteeringa...