Data collection and housing-led policy are key to tackling homelessness

Following triple-digit rates of increase in child and family homelessness since 2014, a decrease in the number of homeless people accessing emergency accommodation was evident in the months of November and December 2019. A month-on-month decrease in December figures is expected, as Christmas approaches and more emergency beds are made available, however the decrease in November is unusual. Is this a statistical anomaly or is child and family homelessness really decreasing? With the state of data collection on homelessness in Ireland described as “statistical obfuscation if not corruption” in a 2019 report commissioned by the European Commission, it can be hard to tell. There is a need for robust data collection in all policy areas, but particularly those affecting the most vulnerable. In its Policy Brief on Affordable Housing: Better data and policies to fight homelessness in the OECD, the OECD looks at ways to improve data collection, and therefore evidence-based policies, on homeless.

1.9 million people across the OECD are deemed to be homeless, however as there is no common definition of homelessness, this is admittedly likely to be underestimated. In Ireland, 0.13 per cent of the population are accounted for in official homelessness data, which is based on people accessing emergency accommodation paid for by Local Authorities. These data discounts rough sleepers (of which there are approximately 90 according to the Winter Rough Sleeper Count conducted by the Dublin Regional Homeless Executive); those staying with families and friends; victims of domestic violence staying in refuges; asylum seekers; or, following a directive from the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, homeless families who have been temporarily accommodated by their Local Authority in temporary, own-door accommodation owned by the Local Authority. Without taking a full account of who is homeless, and what their individual circumstances are, we cannot fully tackle it.

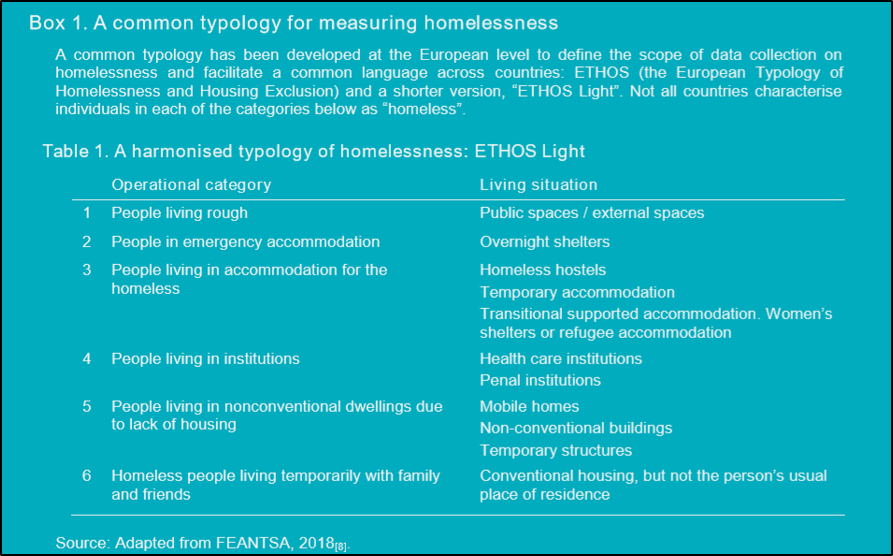

The ETHOS typology, developed at a European level, seeks to provide a composite definition of homelessness for the purposes of data collection. This typology (Box 1, taken from the OECD Policy Brief) would require an inter-Governmental approach to data collection on homelessness, requiring data from the HSE and Department of Health, and the Department of Justice and Equality, however much of this data should already exist within the various systems, or be possible with relatively small adaptations.

Of course, adopting a broader definition of homelessness will result in an increase in official data. With housing being one of the highest reported issues in the recent General Election, the certainty of increasing homeless figures is a political minefield for a new Government. However, pretending that a proportion of the homeless population don’t exist has not been a successful strategy either. Broad definitions exist in countries such as Denmark, Finland, Norway and Poland, all of which have a lower proportion of homelessness as a percentage of the total population than Ireland[1]. In fact, Norway and Finland experienced a decline in homelessness while Ireland’s figures were rising[2].

Homelessness and housing are intrinsically linked. Housing-led approaches in Norway and Finland are credited with the decreases in homelessness in both countries. Norway developed an inter-Governmental housing strategy – Housing for Welfare: National Strategy for Housing and Support Services 2014-2020, while Finland launched a Housing First programme as part of its national strategy to eliminate long-term homelessness. In its Action Plan for Homelessness in Finland 2016-2019, Housing First was a key part of addressing social exclusion, ensuring that housing is secured as a first step.

According to the OECD, better data collection on homelessness should be a priority to assess and monitor homelessness trends. This ability to fully assess trends would then support tailored interventions to prevent homelessness and provide supports for homeless people that meet their needs and provide sustainable solutions.

The OECD policy brief ends with a series of recommendations for policymakers to tackle homelessness:

- Collect homelessness data on a regular basis, integrate diverse data sources and expand the methodological toolbox to get a better understanding of the challenges and needs of different homeless populations

- Invest in homelessness prevention, including by making housing more affordable

- Tailor support to the diverse needs of the homeless population

- Develop broad-based support for homelessness strategies

- Facilitate co-operation among government authorities at different levels of government, along with non-governmental actors, to develop and implement tailored local strategies

- Monitor the effects of homelessness interventions to identify the most effective housing and social support interventions and facilitate cross-country learning

These are measures which could be taken by Ireland to ensure that homelessness is comprehensively addressed, and declines are not just based on statistical obfuscation.

[1] https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC3-1-Homeless-population.pdf

[2] Norway experienced a 40% decline between 2012 and 2016; Finland experienced a 39% decline between 2010 and 2018