Direct provision is inhuman, degrading, and increasingly unfit for purpose

Ireland's current means for accommodating asylum seekers is increasingly unfit for purpose, and the practice of keeping people in such cirucmstances for - as in some cases - several years is inhuman.

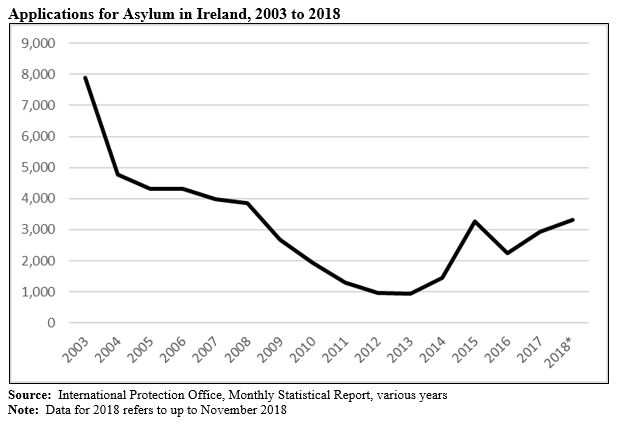

Asylum seekers are defined as those who come to Ireland seeking permission to live in Ireland because there are substantial grounds for believing that they would face a real risk of suffering serious harm if returned to their country of origin. The chart below shows the number of applications for asylum in Ireland between 2003 and 2018.

Up to November 2018, the number of asylum applications to Ireland increased by 27 per cent on the same time in the previous year, with the majority of applicants coming from Georgia, Albania, Syria, Zimbabwe and Pakistan. At the end of September 2018 there were 37 accommodation centres throughout the country accommodating 5,375 people, with only 66 vacancies in total. Since 2002, occupancy has consistently been over 70 per cent of capacity in Ireland’s reception centres. As at the end of September 2018, it was at 97.1 per cent. The largest centre, at Mosney in County Meath, has capacity for 600 people. In September 2018 it held 672, an over-occupancy rate of 12 per cent. Overcrowding is also a feature in four other centres with one centre in Dublin, over-occupied by 25 people, making additional beds available to deal with the demand.

Under Direct Provision as operated in almost all of these centres, asylum-seekers receive accommodation and board, as well as a weekly allowance. The Working Group on Direct Provision has reported a combination of issues contributing to stress and poor mental and physical health for people who are already traumatised and vulnerable, making them among the most excluded and marginalised groups in Ireland. These included:

- significant child protection concerns;

- a lack of privacy;

- overcrowding;

- limited autonomy;

- insufficient play areas and places to do homework for children;

- a lack of facilities for families to prepare their own meals and meet their own dietary needs; and

- no access to employment or formal adult education and training.

Last week Ombudsman Peter Tyndall published a report on his Office’s experience of dealing with complaints from refugees and asylum seekers living in Direct Provision Centres in 2018. 148 complaints were recevied from residents last year. Most complaints related to the refusal of requests to transfer to other centres (32), facilities at direct provision centres (20), accommodation (14) and refusal to readmit residents to centres (13). The Ombudsman also received complaints from residents about food, lack of cooking facilities and availability of transport.

In the report, the Ombudsman notes the positive impact that the ‘right to work’ has had for some residents and the resulting improved mood at many centres. However residents who are in paid employment will be asked to pay a proportion of the cost of providing accommodation in line with their income. The charges will be published by the Reception and Integration Agency. Any complaint about the calculation of the charges can be examined by the Ombudsman.

A total of 2,441 people (41 per cent) have been in direct provision centres for two or more years, and while the numbers who have been there for four or more years have reduced in the past three years, this is still an unacceptable situation. Vulnerable people cannot be sent to live in overcrowded accommodation with little income or access to amenities for such long periods of time.

Budget 2019 increased the weekly allowance for those in Direct Provision, to €38.80 per week for an adult and €29.80 for a child. While welcome, this increase still places the allowance below the recommendationed amounts set out by the Working Group and do not account for inflation in the intervening period. In December 2018, the Centre for Criminal Justice and Human Rights and NASC, together with the School of Law in UCC, published their conference book entitled Beyond McMahon – Reflections on the Future of Asylum Reception in Ireland, a collection of papers presented at the conference of the same name. These papers considered improvements since the publication of the McMahon Report, including the development of draft National Standards for accommodation offered to people in the protection process, limited access to the workplace for asylum seekers who have not received a first-instance decision within nine months and the introduction of the EU Reception Directive. However while these are certainly welcome developments, the papers contained in the book each conclude with a call for further improvements to be made to afford those seeking asylum in Ireland their basic human rights.

As is the case in other areas of accommodation in Ireland, the system of Direct Provision relies heavily on private operators. €67.4 million was spent on Direct Provision centres in 2017, including payments to 27 commercially owned centres. Reports of sick children being denied food and basic care by untrained staff and of former staff of hotels being used as reception centres being redeployed as reception centre staff is concerning. The State must ensure that the holders of these lucrative contracts employ adequately trained staff who can deliver a high level of service to enable the people in their centres to live life with dignity.