Economic lessons from the last recession

Ireland and much of the rest of the world is facing into a major economic recession, perhaps even a depression, as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Stringent but essential measures being implemented are putting the brakes on normal economic activity in all but a few industries.

It also appears that the economic disruption will be much worse than originally feared. According to The Economist newspaper, data for the first two months of the year show that industrial output in China, originally forecast to fall by 3 per cent year-on-year, was down by 13.5 per cent. Retail sales, projected to fall by 4 per cent, were down 20 per cent. Fixed-asset investment, which measures the spending on capital infrastructure, declined by 24 per cent, six times more than predicted. That has sent economic forecasters the world over scurrying to revise down their predictions.

The circumstances and causes of this recession are very different from those that caused the recession in 2008/2009, but there are still lessons that can and should be learned. One of those lessons relates to government’s fiscal response. Faced with a recession that will exceed any in living memory, government must act on a scale that exceeds anything implemented during the financial crisis of a decade ago.

One of the biggest differences between 2020 and 2008/2009 is that the Irish Government can borrow money at a very low cost. At the time the last crisis hit, yields on 10 Year Irish Treasury Bonds were consistently around the 5 per cent mark. That is far more expensive than the present day. Current yields are less than 1 per cent, and have been so for several years. There has even been talk of the possibility of borrowing at negative rates. The availability of this low-cost credit gives government greater room for manoeuvre and should help Ireland avoid a repeat of many of the kind of austerity-type measures implemented in response to the economic downturn a little more than a decade ago.

The role of government spending

Demand in the Irish economy is driven by four factors. The first three are:

- domestic consumption (what people in Ireland are buying)

- investment, and

- exports (driven by the demand abroad for goods produced in Ireland)

When there are significant fluctuations in any or all of these three, the fourth factor – government spending – can and should be used to ‘smooth things out’.

By now, we are all familiar with the concept of ‘flattening the curve’; the euphemism used to describe tactics for tackling the current pandemic, smoothing out the peak of Covid-19 infections as much as possible so as to spread the pain over a longer timeframe and not overwhelm our health system.

While the impending recession is the result of a supply-side shock rather than a crisis of demand, the Irish economy requires a significant injection of government spending to ensure something similar to this ‘flattening’ from an economic standpoint: ensuring that the economic trough is as shallow as possible, and that firms and businesses that would be viable under normal circumstances can continue to exist until such a time as the economy is back on its feet.

Such an approach was not taken a decade ago, and the result was an unnecessarily prolonged recession that led to greater suffering for ordinary Irish people who did nothing to cause it.

Lessons from Ireland’s collapse in construction

While an economy-wide approach is required in 2020, a look at the Irish building industry a decade ago can be an instructive example as to why government intervention is required.

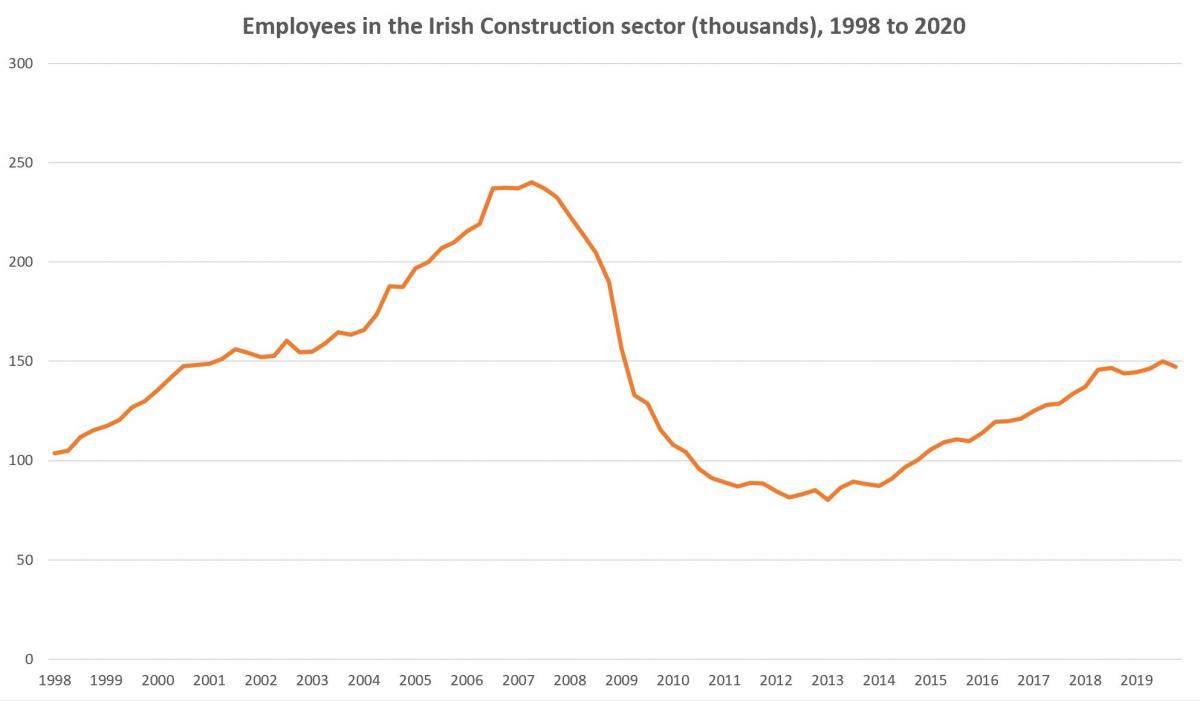

It is well known that construction was the economic sector that suffered most in Ireland during the last recession. Employment in the sector fell from 204,700 in Q2 2008 to 80,300 in Q1 2013. (In Q2 2007, 240,000 people had been employed in the sector – the all-time peak). As has been well documented, this downturn resulted in large-scale emigration of people formerly employed in construction, and a return to education and re-skilling in non-construction roles for thousands of others.

The effects of these developments are still being felt today, as the Irish construction industry struggles to reach a capacity capable of meeting pent-up demand for homes and other projects. Various estimates suggest demand in the region of 30,000 homes per year, while data collated by the CSO indicate that the number of new dwelling constructions reached 20,000 in 2019 for the first time since data-collection began in 2012.

Had the Government of the time, unobstructed by borrowing costs or restrictions like the Stability & Growth Pact, been able to borrow money to support the construction sector and build social housing on the scale needed, we could be in a very different position today regarding our housing needs.

Despite house-building in Ireland taking place at an unprecedented rate before the crash, there were a reported 56,249[1] households with a social housing need in Ireland in 2008, an increase from 43,684[2] in 2005 when the previous housing lists were collated. As of June 2019, a reported 68,693[3] households were on social housing waiting lists. Add to that the number of households in receipt of the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) who are not included on the social housing waiting lists and there is approximately a 100 per cent increase in households in need of a sustainable home since the crash[4].

Had the Government in 2009/2009 borrowed billions of euros and availed of the significant slack in the Irish labour market, particularly in the construction sector, to build social housing, instead of allowing the construction industry to collapse over the four years to Q1 2013, this would have had several positive effects, including:

- It would have helped the Irish construction sector to maintain some of its capacity to ‘ride out’ the fall in demand in the private sector until such a time as the economy had recovered. Among other things, this would mean that the sector would not now be struggling to reach the capacity needed to satisfy current demand.

- It would have saved tens of thousands of jobs at a time when the Irish labour market was seriously struggling.

- It would have negated the need for emigration, particularly of construction workers, on the scale witnessed at the time. This resulted in the loss of a valuable skill-base across the economy, but particularly in construction.

- This investment, effectively a counter-cyclical cash injection into the economy at a time when it could not have been more needed, would have helped to somewhat smooth out aggregate demand in the economy, helping to maintain employment in other sectors as well.

- The current social housing waiting list of almost 70,000 households would be far shorter.

- The Exchequer would be spending far less money on payments like HAP to provide social housing solutions.

- All these effects would have combined to significantly improve the lived experiences of hundreds of thousands of Irish people compared to their actual experience of during those years of austerity.

Unfortunately the Irish Government and their creditors resorted to austerity measures, the results of which are visible today in Ireland’s accommodation crisis among other examples.

The response needed in 2020

As noted above, the economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic is different to that faced a decade ago. While the immediate cause is supply, not demand, there are still lessons to be learned.

While we cannot be certain about when the pandemic might end and society might return to something resembling normality, we can be relatively sure that the immediate cause of the downturn will subside in a matter of months, rather than years. It is important that when this happens, firms, producers and employees are, to the greatest extent possible, in a position to return to what they were doing pre-pandemic.

Emigration is no longer the economic safety-valve is was 10 years ago: Virtually every country in the world is in the same position.

The Irish government is to be commended for the actions taken thus far in the crisis, acting quickly and decisively to ensure supports are in place for workers and firms in the immediate term. But more – much more – will be required

Only governments, at a national and supranational level (i.e. the European Union and international institutions) are in a position to prop up the economy and to provide the finances necessary in the timeframe required.

As noted by the OECD, the most urgent priority is to minimise the loss of life and negative health effects. But the pandemic has also set in motion a major economic crisis that will burden our societies for years to come. Some of the initial responses have been commendable. But only a combined, coordinated international effort will meet the challenge.

Only with immediate, large-scale and co-ordinated actions will the economy be ready for a quick and vigorous restart. The aim should be to ensure that in time, otherwise-viable firms have not been allowed to go out of existence as a result of a temporary downturn in demand, or because they were restricted from supplying their products or services due to social distancing or other pandemic-related requirements.

In short, only governments are in a position to ensure that what is currently a short-term supply crisis does not become a long-term demand crisis.

[1] https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/migrated-files/en/Publica...

[2] https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/migrated-files/en/Publica...

[3] https://www.housingagency.ie/sites/default/files/SHA-Summary-2019-DEC-20...

[4] HAP was introduced in September 2014. Households in receipt of HAP are not counted as part of the social housing waiting lists as they are deemed to have had their social housing need met. In 2008, households in need of social housing and accommodated in the private rented sector would likely have received Rent Supplement. Households on Rent Supplement are counted as part of the social housing waiting lists.