HAP is not a real Social Housing Solution

A publication on Social Housing in Ireland 2019 – Analysis of the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) Schemereleased by the CSO in November 2020 indicates that some 57,630 households in need of social housing were accommodated in the private rented sector by the end of 2019. Social Justice Ireland has long-argued that this is not a sustainable housing model for low income households, given the recent volatility in the private rented sector.

County Breakdown

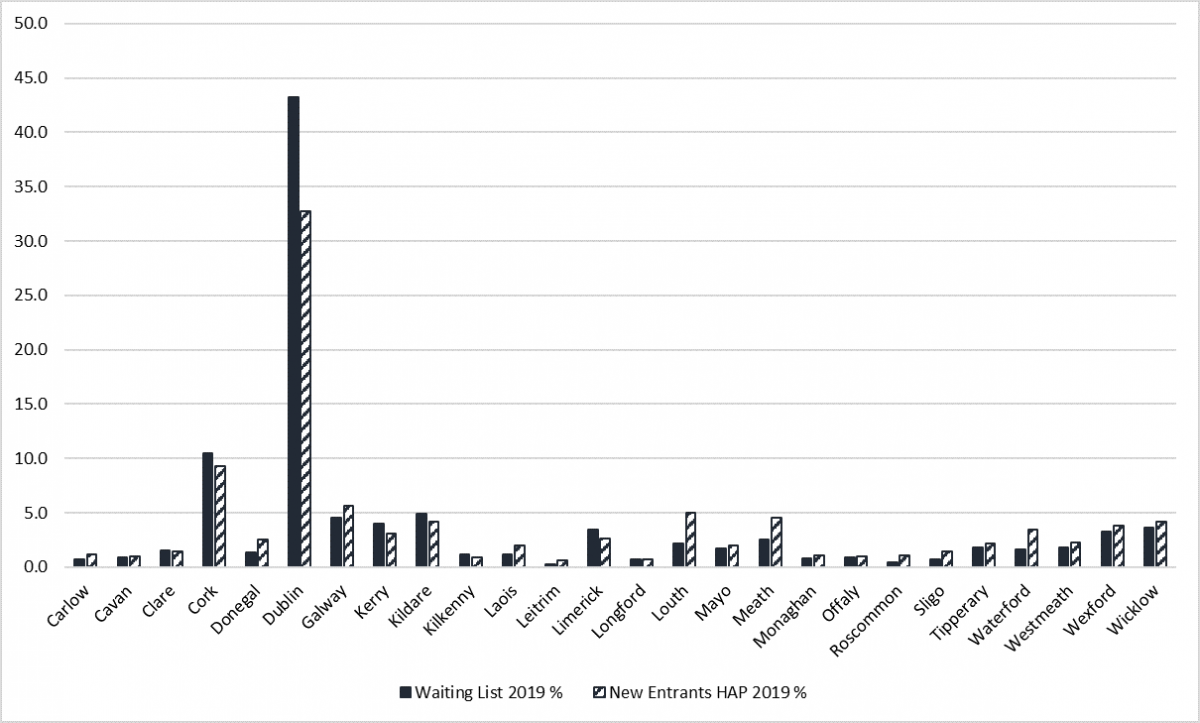

According to the latest data on social housing, the Social Housing Needs Assessments 2019, published in December 2019, there were 68,693 households on the waiting list for social housing in 2019[1]. Of these 68,693 households, the highest proportion is in Dublin (43.3 per cent), followed by Cork (10.5 per cent), Kildare (4.9 per cent) and Galway (4.6 per cent). Dublin also accounts for the highest proportion of new households into the HAP Scheme in 2019 (32.7 per cent), followed by Cork (9.3 per cent), Galway (5.6 per cent) and Louth (5 per cent) (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Households on the Social Housing Waiting List 2019 and New Entrants into the HAP Scheme 2019

Source: Data extracted from the Summary of Social Housing Needs Assessments, 2019 (Housing Agency, 2019) and Social Housing in Ireland 2019 – Analysis of the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) Scheme (CSO, 2020)

Overall, however, the lowest proportion of rental properties in HAP were in Dublin City and Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown in 2019 where rents are high and, in most cases, above HAP rent limits. HAP tenancies accounted for 41.8 per cent of all properties registered with the Residential Tenancies Boards (RTB) in Louth in 2019, and just 4.7 per cent in Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown.

HAP and Social Housing Waiting Lists – Length of Time

The CSO also analyses data relating to new entrants to HAP with reference to the Social Housing Waiting Lists 2016-2019 and found that more than four in ten HAP tenants (44.4 per cent) waiting less than a year on the social housing waiting lists before first entering the scheme. When we consider that 48.7 per cent of households on the social housing waiting list in 2019 were waiting four years or more, and 26.9 per cent, or 18,454 households, were waiting more than seven years, there is a clear disconnect between new entrants to HAP and those households who are most in need of sustainable accommodation.

Employment Sectors

According to the CSO Report, the most common employment sectors for new entrants to the HAP Scheme were Wholesale & Retail, Accommodation and Food, and Health. This presents two issues:

- These are precarious sectors, often characterised by low pay and precarious contracts. The impact of Covid-19 on employment has been devastating, raising concerns about the sustainability of these tenancies once restrictions on evictions cease.

- This is not reflective of the employment status of the households on the social housing waiting lists. The majority of those households (60.3 per cent) are entirely dependent on social welfare income.

Residential Status

Of those new entrants to HAP referred to in the CSO Report as being linked to the social housing waiting lists between 2016 and 2019 were identified as living in the private rented sector, and almost 40 per cent were dependent on Rent Supplement as the primary basis of need. According to the 2019 Summary of Social Housing Needs Assessments, over half (52.8 per cent) of households on the social housing waiting list in 2019 were already living in private rented accommodation, compared to 59.1 per cent the previous year. This decrease, coupled with the corresponding increase in the proportion of households living with parents (21.5 per cent, compared to 19.1 per cent in 2018), relative or friends (8.9 per cent, compared to 7.6 per cent in 2018) or emergency accommodation (8.5 per cent, compared to 6.6 per cent in 2018) shows just how unsuitable the private rented sector is at providing sustainable housing for low income households.

Rather than providing long-term social housing to households most in need, the Housing Assistance Payment is a subsidy to the private rented sector. We need to rethink our relationship with housing, particularly as part of our new Social Contract with the State. Social Justice Ireland again calls on Government to put a social housing target in place of 20 per cent of all housing stock by the year 2030.

[1]Summary of Social Housing Assessments 2019 | The Housing Agency