The impact of Early School Leaving

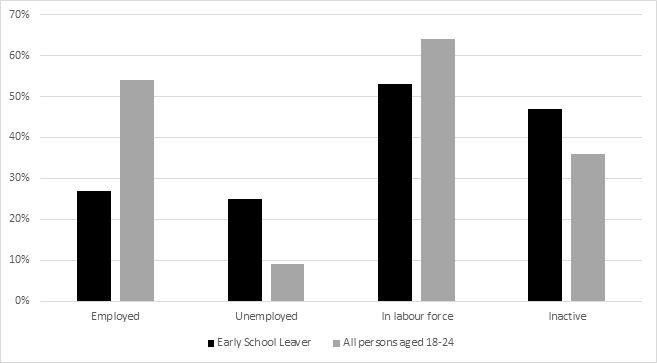

According to the latest data from the CSO (see chart 1) an early school leaver is three times as likely to be unemployed than the general population aged 18-24.

Chart 1: Labour Market Status for Early School Leavers and total population 18-24 year olds Q2 2019

Source: (CSO, 2019).

Only one in four of them are in employment compared to the general population for that age group and just under half (47 per cent) are not economically active. The CSO analysed the outcomes for students who started second level education in 2011 – 2013. When comparing early school leavers to those who completed the Leaving Certificate the report found that just 43.8 per cent of early school leavers were in employment compared to 74 per cent of their peers who finished school, and that the median earnings for early school leavers were €65 less than their peers(€345 per week compared to €410 per week).

Despite the progress made on early school leaving these figures are a cause of concern. The poor labour market status of early school leavers as outlined in chart 1 points to the need for a continued focus on this cohort and on addressing educational disadvantage. As we move towards a future where digital transformation will disrupt the labour market, having the greatest impact on people with lower levels of education and skills, it is important that this cohort are not left behind.

Ireland’s National Reform Programme refers to the DEIS scheme as a key measure in supporting the achievement of the national target in regard to early school leaving. Evaluation suggests that the DEIS programme is having a positive effect on educational disadvantage – including on retention rates (to Leaving Certificate). However, unfortunately the DEIS scheme suffered cut-backs in Budget 2012, which were subsequently only partially rolled-back. More generally, capitation grants for schools have been cut by more than 10 per cent following the economic crisis in 2008 and subsequent Budgets have not restored the value of these cuts. Increased and sustained funding and support for the DEIS scheme is required if it is to continue to support improvements in literacy, numeracy and early school leaving.

Clearly, despite making steady progress, Ireland still faces challenges in the area of early school leaving and young people not engaged in employment, education or training (NEETs) in disadvantaged areas. The gap between retention rates in DEIS and non-DEIS schools has halved since 2001, but it still stands at 8.5 per cent[1]. Government must work to ensure that schools in disadvantaged areas are supported to bring the rate of early school leavers to below Ireland’s country-specific target of 8 per cent under the EU2020 Strategy and towards the national rate of 4 per cent. Overall, we believe that the situation calls for a long-term policy response, which would encompass alternative approaches aimed at ensuring that people who leave school early have alternative means to acquire the skills required to progress in employment and to participate in society. The recent Action Plan for Increasing Traveller Participation in Higher Education contains a broader view of access and recognises the need to support traditional and non-traditional routes to higher education. This broad view of access is pertinent when it comes to dealing with the issue of early school leaving. Approaches in the area of adult literacy and lifelong learning are important in this context, discussed later in this Chapter.

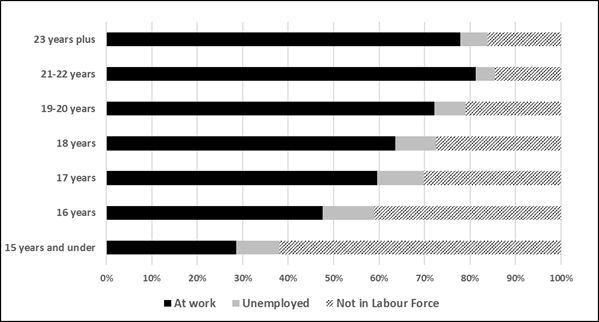

The socio-economic effects of inequality in education are clearly seen in Chart 2.

Chart 2: Economic Status by Age Education Ceased, 2016

Source: CSO, Census 2016

The longer a person stays in education the more likely they are to be in employment. The risk of unemployment increases considerably the lower the level of education. Participation in high quality education has benefits not only for young people themselves but also for taxpayers and society. These benefits typically last over the course of an individual’s lifetime. According to the OECD adults with a tertiary degree in Ireland earn on average 81 per cent more than adults with upper secondary education. They are more likely to be employed, the employment rate is 11 percentage points higher for degree holders than for those with an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education. The benefits of investing in education, both to the individual, to the economy and to society, far outweigh any initial outlay of resources. This is something that should be at the forefront of decisions regarding the investment and resourcing of our education system as a whole.

The OECD PIAAC (Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies) study found that the children of parents with low levels of education have significantly lower proficiency than those whose parents have higher levels of education, thus continuing the cycle of disadvantage.[2] This is echoed in the 2018 report by the OECD on education in Ireland which found that the educational attainment levels of 25-64 year olds are very similar to that of their parents and that 40 per cent of adults whose parents did not attain upper secondary education had also not completed upper secondary education.

The inter-generational transmission of low levels of skills and educational qualification underscores the need for high-quality initial education and second-chance educational pathways, as well as improved access to, and relevance of, lifelong learning and community education opportunities (with both academic and vocational tracks). Clearly ongoing work with parents in disadvantaged areas is of key importance in encouraging support of children in education.

[1] https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Statistics/Key-Statistics/educa...