Inadequate housing means c.14,700 households unable to social distance - #MoveTheVulnerableOut

Almost since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the advice has been to stay at home. Social distancing can help flatten the curve and save lives. On the 24th March, the Government introduced stricter measures regarding social distancing, urging people to leave their homes only when absolutely necessary and restricting gatherings to four people or less unless all are from the same household. These are serious times. However, for thousands of the most vulnerable people in society, social distancing just is not an option. A Government that is urging people to stay apart has been forcing these people to stay together.

The Homeless

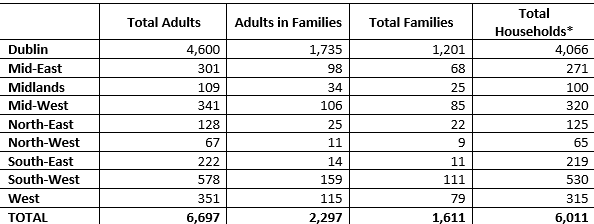

January 2020 saw the highest month-on-month increase in people accessing emergency homelessness accommodation (at 5.3%) since February 2018 (a 7.7% increase). In the week 20-26 January 2020, 10,271 people accessed emergency homeless accommodation – 6,697 adults and 3,574 children. Analysis of the data contained in the Homelessness Report for January 2020[1] indicate that these 10,271 people account for approximately 6,011 households, over 4,000 of which are in Dublin (Table 1).

Table 1: Households accessing emergency homeless accommodation, January 2020

Source: Analysis of Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government Homelessness Report January 2020

*Notes: This may be slightly less as the calculation does not account for couples.

These 6,011 households (of whom 1,611 are families) are living in shared accommodation in hotels, B&Bs and Family Hubs. Many do not have their own cooking facilities. Those who are forced to vacate this accommodation every morning must walk the streets. With the closure of libraries, cafes and many retail outlets, there are very few places for them to go. Risk of infection and cross-contamination is high, particularly for the 1,611 families.

Direct Provision

The latest publicly available statistics from the Reception and Integration Agency refer to November 2018[2], when there were a reported 5,928 people living in Direct Provision across the country. A breakdown of the families in RIA Accommodation contained in this statistical report show there were 479 single parent families, 416 partner families and 2,866 single people in Direct Provision. A total of 3,761 households[3]. This number has likely increased in the intervening 16 months. It would not be unreasonable to assume there are now c.4,000 households in Direct Provision in March 2020.

In December 2019, three reports were published which highlighted the inadequacy of the conditions for people in Direct Provision centres across the country[4]. Among the concerns raised in these reports were the cramped living conditions, the lack of available recreational space, and the sharing of rooms with strangers.

The Department of Justice has said it will “pilot an off-site self-isolation facility” for asylum seekers suspected of having COVID-19 living in Direct Provision centres. One of the many difficulties with this approach is that COVID-19 can be asymptomatic for an initial period, particularly in children who are vectors of the disease. A pilot will not be able to contain an outbreak where thousands of people are living in cramped accommodation. The solution is in prevention.

Travellers

The 2018 Estimate of Traveller Accommodation[5] indicates that an estimated 927 Traveller families were living in shared accommodation in 2018. This represents 8 per cent of all Traveller families and is an increase of 168 per cent on 2008.

The Report of the Traveller Accommodation Expert Review Group[6], published in July 2019, included reference to a submission which described the use of the term ‘shared accommodation’ as a euphemism for “chronic overcrowding” (p15) and spoke of Travellers being trapped as they have nowhere else to go.

There are persistent, systemic issues with the provision of Traveller-specific accommodation. As of November 2019, a reported 14 Local Authorities had yet to spend any funding in this area, with just €4 million of an allocated €13 million being drawn down[7]. Lack of facilities and unsanitary conditions in some Traveller accommodation, particularly so-called unauthorised halting sites, present a serious health risk in normal times. In the midst of a highly infectious pandemic, they could be catastrophic.

Overcrowded Households in need of Social Housing

There are a reported 68,693 households on the social housing waiting lists[8]. Of these 3,649 (5.3%) reported overcrowding as being their main need for social housing. While the overall number of households in need of social housing reportedly decreased by 4.4 per cent between 2018 and 2019, those reporting overcrowding increased by 5.3 per cent.

These households cannot self-isolate. They cannot socially distance. Because they are likely to be intergenerational, with children living with parents and grandparents, they cannot stay away from their elderly relatives. A lack of social housing has contributed to an increased risk for poorer families.

Refuges

Domestic Abuse Services National Statistics 2018[9] published by Safe Ireland indicate that 1,138 women and 1,667 children were accommodated in a refuge in 2018. Some 9,971 individual women and 2,572 individual children received some supports from domestic violence refuges in that year and services were unable to provide accommodation for 3,256 requests because they were full.

Due to our ratification of the Istanbul Convention, Ireland should have 472 places for victims of domestic violence, but has only 141[10].

The current crisis highlights the need to protect women in communal spaces from infection and cross-contamination. The need for social distancing, requiring extended periods in the home, also highlights the need for thousands of women to find a safe space.

Short- and Medium-Term Solutions

In terms of housing, there are some solutions.

Reports from Census 2016 indicate that there are 183,312 vacant properties across Ireland, 245,460 when holiday homes are included[11]. The emergency powers used to limit the Constitutional protection of property rights and restrict tenant evictions could be extended to requisition suitable residential properties for use by vulnerable households.

Daft.ie has reported a 13 per cent increase in available rental properties in the year to March 2020 (with a 64% increase in 1 and 2 bed rentals in Dublin) as students return home from college and tourists cancel bookings of short-term lettings. These now vacant properties could be used by vulnerable households to protect themselves in this time of crisis. Landlords whose tenants have been affected by COVID-19 are potentially eligible for a payment break on their Buy-to-Let mortgage for a period of up to three months. This flexibility could be made available to landlords who make their properties available to support vulnerable households for the duration of this crisis, with a State-guarantee for any additional interest accruing as a result of the payment break in the event that this is not waived by the lender.

Another possibility is that the Government could provide a modified Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) to landlords who make their properties available in these circumstances, providing them with an income they would otherwise not have and providing vulnerable households with somewhere to safely engage in social distancing.

These are not long-term solutions, and much more will be required into the future when this crisis passes.

We are in an extraordinary time. We need an extraordinary response.

[1] https://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/homelessness/homeless-report-january-...

[2] http://www.ria.gov.ie/en/RIA/November%202018%20-%20Final.pdf/Files/Novem...

[3] This calculation does not account for couples within the single numbers.

[4] https://www.socialjustice.ie/content/policy-issues/international-migrant...

[5] https://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/special-housing-needs/traveller-accom...

[6] https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/2019_j...

[7] https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2019-11-19/660/#pq_660

[8] https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/sha_su...

[9] https://www.safeireland.ie/policy-publications/

[10] https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/2019-12-11/38/

[11] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp1hii/cp1hii/vac/