A Just Transition for Farmers

Just Transition for Farmers

Restructuring agriculture and supporting and incentivising farmers to move to more sustainable agricultural practices is integral to a Just Transition in Ireland. One of the fundamental principles of a Just Transitions is to leave no people, communities, economic sectors ir regions behind as we transition to a low carbon future. A clear pathway for the farming community outlining how they will be supported as part of a Just Transition, and the benefits of sustainable farming practice to our environment, natural capital and to their household incomes is essential.

Income

About half of farm families require off-farm income to remain sustainable. While recent gains in agriculture-based incomes have had an impact on the most commercial farms, solutions to the wider income problems require a broader approach for all rural families, combining an economic and social dimension. The impact of Covid-19 on regional and rural employment will have a negative impact on the incomes for farming households.

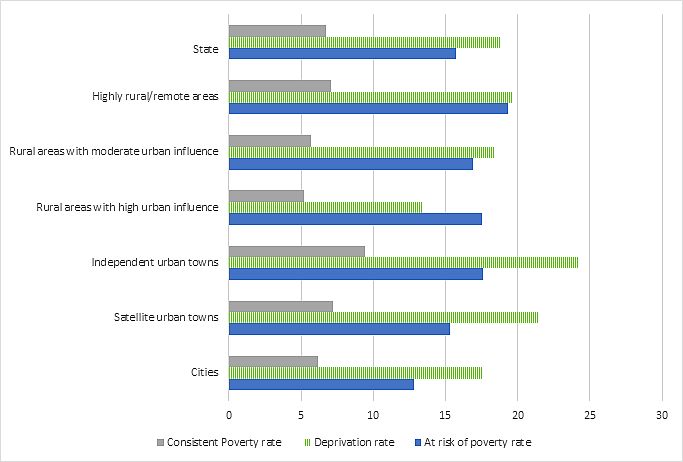

A consistent trend over the past decade is the increased at-risk-of-poverty rate in rural areas. The latest figures show the at-risk-of-poverty rate of rural areas higher than in urban areas[1]. This is a persistent pattern. There is significant regional variation within these figures, and the Northern and Western region has the highest at-risk-of-poverty rate and the lowest median income in the State. Worryingly, this region has also seen one of the greatest reductions of full-time employment since 2008 and has been one of the slowest to see the gains from increased employment growth. The low incomes in the Northern and Western region are also mirrored in farm incomes. Chart 1 gives a breakdown of poverty and deprivation rates by area type.

Chart 1: Key Indicators of Poverty by Area Type, 2017

Source: CSO Statbank 2019

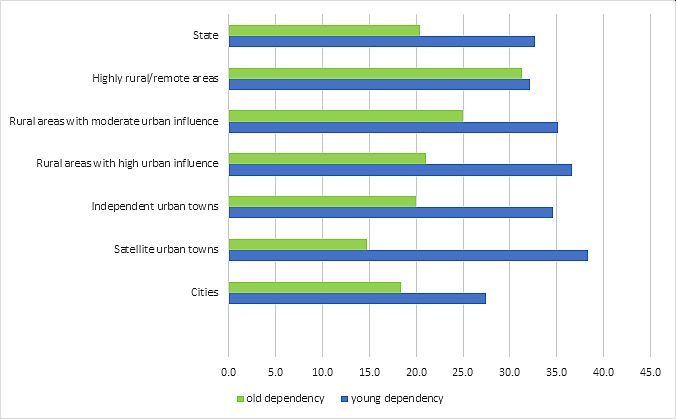

Chart 2: Dependency ratios by age group and area type 2016

Source: CSO Statbank 2019

Charts 1 and 2 give an outline of some of the challenges facing rural areas, namely higher dependency ratios and higher rates of poverty and deprivation. Recent data shows that remote rural areas have the highest total dependency ratio in the State. These areas also have the highest average age in the State, have the highest rate of part-time workers in the State (23.8 per cent) and, at 19.3 per cent, the highest poverty rate[1].

The data in these charts give an insight into the challenges that face rural and regional communities.Rural and regional policy has to grasp with issues such as higher poverty rates, lower median incomes, higher dependency ratios, distance from everyday services and a higher rate of part-time employment. It is worth reiterating that our success in implementing policy to address these challenges will determine how well placed rural Ireland will be to respond to other challenges such as the impact of Covid-19, the transition to a sustainable society and the future of work.

Farm Incomes

In 2018 average family farm income was €23,483, a decrease of 21 per cent on the previous year[2]. The financial impact of very poor weather in 2018 had a significant impact on farm incomes with dairy farm incomes falling by one third. As ever, there was a wide variation in farm incomes, with 29 per cent of farms earning an income of less than €5,000 in 2018, 15 per cent earning between €5,000 and €10,000 per annum and 31 per cent earning between €10,000 and €30,000 per annum.

Average farm income is highest on dairy farms and in the South East region. The Northern and Western region is the most disadvantaged region with the lowest farm income and the highest reliance on subsidies. Some key farm statistics from the Teagasc Farm Survey[3] include:

- Average family farm income was €23,483 in 2018.

- 44 per cent of farms earned a farm income of less than €10,000 in 2018.

- 53 per cent of dairy farms report an income of more than €50,000 in 2018.

- Almost two-third of cattle-rearing farms earned less than €10,000 in 2018.

- The average direct payment in 2018 was €17,244.

- Direct payments accounted for 79 per cent of all payments received to dairy farms, 84 per cent to tillage farms and 57 per cent to cattle-rearing farms.

- Just 32 per cent of farms are considered economically viable with 34 per cent considered vulnerable.

- 52 per cent of farm households have off-farm employment and 40 per cent of cattle farmers work off-farm.

These statistics mask the huge variation in farm income in Ireland as a whole. Only a minority of farmers are, at present, generating an adequate income from farm activity and even on these farms income lags behind the national average. Farm incomes are also inconsistent, as the prices of commodities fluctuate and gains are predicated on expanding dairy production which runs contrary to our climate commitments.

The abolition of milk quotas in 2015 has resulted in increased supply of milk from the European Union (EU). Many Irish farmers borrowed to invest to scale up production with the expectation of demand from Russia, China and other world markets. Whilst dairy farming is the most profitable form of farming in Ireland, it is also the most volatile due to price fluctuations and a high dependency on them is not a sustainable way to maintain farm incomes.

It is clear that farming itself is not enough to provide an adequate income for many families as evidenced by the over reliance on direct payments and the number of farmers engaged in off-farm employment. Of further concern is the age profile of those engaged in farming. In 2016, around a quarter of farm holders in Ireland were aged 65 years and over, and just 5 per cent were aged less than 35 years[4].

Advances in technology and mechanisation have meant that many farmers can seek alternative ways to generate income. From the mid-1990s, off-farm employment by farmers increased significantly. However, during the recession, many of these jobs were lost. A strong potential has been identified for alternative farm enterprises such as niche tourism and food production. However, these need significant support, and are likely to attract younger and better educated farmers.

Welfare payments also support farmers. In 2018 there were 6,535 families comprising 9,231 adults and 5,109 children receiving the Farm Assist Payment[5]. The Rural Social Scheme (RSS) had 3,103 participants and by extension supported 2,143 children and 1,232 adults in 2018.

It is important that adequate supports are put in place to facilitate all stakeholders in Agrifood to deal with the transition to a clean, green society and economy. The AgriFood Strategy to 2030 should support and resource to move to more sustainable agricultural practices with short supply chains and following the ‘Farm to Fork’ principles in order to reduce our emissions and ensure that our land management is sustainable[6].

It is vital that investment in infrastructure in the regions and rural areas is expedited to ensure rural economies can diversify and adapt to support thriving rural communities. A step change in policy is required, focussed on building sustainable and viable rural communities, including farming and other activities. In implementing this policy there needs to be significant investment in sustainable agriculture, as well as rural anti-poverty and social inclusion programmes, in order to protect vulnerable farm households in the transition to a rural development agenda.

The Central Bank published a paper on the uncertain outlook for Irish Agriculture in 2019[7]. This analysis shows that beef and sheep farms (around 7 out of every 10 farms) face significant viability challenges and are heavily reliant on direct payments. The West, Mid-West and Midland regions are more exposed to negative shocks. The report concludes that low profitability and a high reliance of farm incomes on direct payments represent an important weakness in the sector and provides the context in which all other risks facing Irish agriculture should be considered. The report concluded that any future negative shock – even one less material than Brexit – would further expose the underlying weaknesses in the sector. Covid-19 is clearly such a shock, and any recovery and investment plan should focus on sustainable agriculture, supporting farm household incomes and putting our agriculture sector firmly on a path towards meeting climate targets.

CAP and Agriculture Policy

The European Commission’s proposals for the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for 2021 to 2027 stipulate that at least 40 per cent of the CAP’s overall budget and at least 30 per cent of the Maritime Fisheries Fund would contribute to climate action. This will have implications for Irish agriculture and fisheries as the new system will incentivise more sustainable practices. However, the new CAP will also have a reduced budget meaning there are less funds to be allocated.

The EU-Mercusor trade agreement undermines the commitments and ambitions of the ‘European Green Deal and the focus on climate action and sustainability of CAP 2021-2027’. If ratified by the European Parliament the EU-Mercosur trade deal will eliminate tariffs on roughly 90 per cent of Mercosur’s exports to the EU over 10 years – chiefly agricultural products such as beef, poultry, and fruit and in turn, EU companies would pay less tax to export products – mostly machinery, car parts, and dairy products like cheese – to Mercosur.

This deal would lock the European Union into an unsustainable economic model, entirely at odds with the stated aims of the Green Deal for Europe. How is importing significant amounts of agricultural products such as beef, poultry and fruit (which the EU itself already produces) and the increased emissions that this will inevitably lead to supporting one of the stated aims of the Green New Deal – Greening of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) with a Farm-to-Fork strategy. What incentive is there for Irish famers and their counterparts across the European Union invest in sustainable forms of agriculture and the Farm-to-Fork Strategy if they have to compete with agricultural imports from the other side of the world? At a National and EU Level policy should support and incentivise sustainable agricultural practice and the incomes for farm families, not undermine it.

The European Commission intends to launch a ‘Farm to Fork’ Strategy in Spring 2020, along with a broad stakeholder debate covering all the stages of the food chain, and paving the way to formulating a more sustainable food policy. The ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy will pave the way for a transition for a sustainable food system based on circular economy principles. Irish agriculture policy should be at the forefront of developing short supply chains in order to progress the ‘Farm to Fork’ proposal. This would not only assist farmers in negotiating a fair price for their produce, it would also ensure consumers have access to locally produced food which is more sustainable in the long term.

Sustainable land management is crucial to Ireland moving to more sustainable agricultural practices. Sustainable land management is the use of land resources to meet changing human needs while ensuring the long-term productive potential of these resources and the maintenance of their environmental functions. The adoption of sustainable land management would reward sustainable forms of agriculture, put Ireland in a good position for the next round of CAP negotiations and acknowledge the role of farmers as custodians of this vital national asset.

Ireland is in the process of developing the next Common Agricultural Policy Strategic Plan, This represents an opportunity to move to more sustainable forms of farming and land management. CAP payments are likely to focus on incentives for farmers to move to more sustainable methods of production. Six key principles for the CAP Strategic Plan for Ireland were developed by a group of independent scientises in 2019 at a workshop funded by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht aimed at providing an ecological evidence base to inform the future of the Common Agricultural Policy in Ireland[8]. These principles are:

- Farm for Food Security.

- Nature has Limits.

- Quantity, Quality and Connectivity Matter.

- One Size CAP doesn’t fit all.

- Strengthen the links.

- Nature needs long-term but flexible planning.

These six principles, alongside sustainable land management and developing short supply chains for farmers and consumers, should be adopted by Government as the basis for the CAP 2021-2027 Strategic Plan. The refocusing of the CAP budget to climate action presents an opportunity for farmers to invest in sustainable forms of agriculture and the Farm-to-Fork Strategy has the potential to deliver on short supply chains for farmers, and address some of the issues of product pricing for Irish farmers.

Policy options

Ireland should also focus on developing alternative agricultural models and move away from intensive livestock farming. Irish dairy farms produce up to three time more greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions than other farming sectors and yet the dairy sector has been earmarked by Government for continued expansion[9]. The Teagasc report also found that increase in herd sizes on dairy farms is undermining any gains from more efficient and sustainable farming practices. This type of policy incoherence cannot continue. While reducing agricultural emissions will be difficult, it is necessary. In order to do so it is vital that Food Wise 2030 reflects the Farm-to-Fork principles of the European Commission and set ambitious targets to reduce our agricultural emissions. Transition to a sustainable food and farming system, based on circular economy principles, could ensure the viable future of this industry. It would help restore freshwater resources, incentivise sustainable land and forest management and other ecosystems.

Support for sustainable agricultural practice is important to ensure the long-term viability of the sector and consideration must also be given to how the projected increase in agricultural emissions can be offset. It is important that the agriculture sector be at the forefront of developing and implementing sustainable farming practices and be innovative in reducing emissions. With regard to our national and international climate commitments it must be asked what agricultural policy will be best-placed to ensure Ireland meets its national and international targets: Is it a policy of agricultural expansion and increased emissions to reach additional markets or is it a policy of ensuring Ireland produces the food required to meet our population needs, that Irish farmers are supported in pursuing short supply chains and ensuring quality Irish agricultural products get a fair price in Irish supermarkets? Irish agricultural policy should also support our ODA policy and not undermine the agricultural sector in the developing world in providing the food required to meet their own population needs and getting a fair market price for their own produce.

[1]https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-urli/urbanandrurallif...

[2]https://www.teagasc.ie/publications/2019/teagasc-national-farm-survey-20...

[3]https://www.teagasc.ie/publications/2019/teagasc-national-farm-survey-2018-results.php

[4]https://www.cso.ie/en/statistics/othercsopublications/ireland-factsandfigures2018/

[5]https://www.welfare.ie/en/downloads/2018-Report.pdf

[6]https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/food_farm2fork_20191212_qanda.pdf

The Farm to Fork Strategy aims to ensure farmer' and fishers' position in the value chain, encourage sustainable food consumption and promote affordable and healthy food for all. The principles of the strategy are designed to support all three aspects of sustainability – economic, environmental and social.

[7]https://www.centralbank.ie/docs/default-source/publications/economic-let...

[8] For a further detail and information on the principles and outcomes of the workshop see https://www.cap4nature.com/

[9]https://www.teagasc.ie/media/website/publications/2019/2017-sustainability-report-250319.pdf

[1]https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-silc/surveyonincomeandlivingconditionssilc2018/