Local Responses critical in wake of COVID-19

Community volunteers have rightly been in receipt of high praise for their response to the COVID-19 crisis. This community spirit is to be commended, however harnessing that engagement for real social change remains a challenge in the context of a highly centralised Government structure.

Decision Making

Ireland has a particularly centralised Government. In their chapter Democratic Revoluation?Evaluating the Political and Administrative Reform Landscape after the Economic Crisis, Reidy and Buckley list the degree of Government centralisation as one of four key symptoms in the “diagnosis of failure across the Irish political landscape”[1].

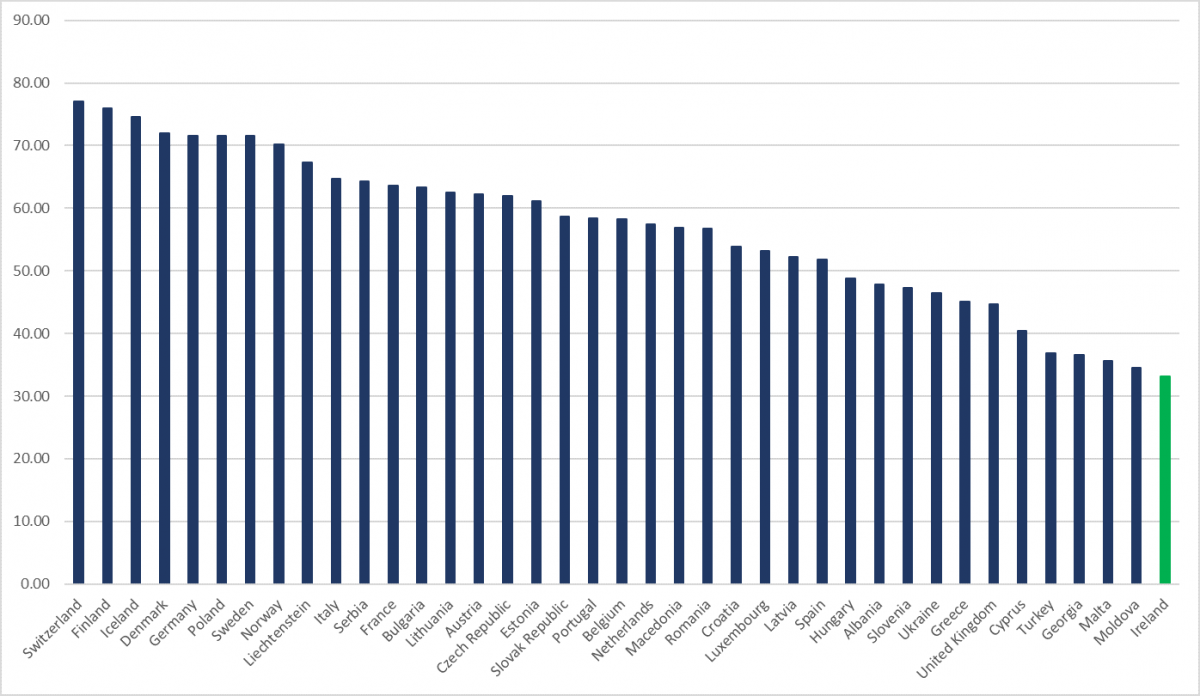

According to the European Commission’s Self-Rule Index for Local Authorities, a measurement of Local Government autonomy based on a common code book developed to produce a ‘Local Autonomy Index’[2], Ireland ranked the lowest in terms of autonomy, even after the introduction of the Local Government Reform Act, 2014 (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Local Autonomy Index, 2014

Source: Local Autonomy Index Datasets, European Commission, 2015

The Local Autonomy Index Ireland Report cited 2013/2014 as being the period in which the biggest changes happened at Local Government level since the introduction of the dataset in 1990, with “the abolition of town and borough councils, amalgamation of certain city and county councils, introduction of a new residential local property tax and the loss of water services from the local authorities to a new public utility company.” (page 1). Many of these “managerial, administrative and other public sector reform measures” were ushered in on the back of the Troika Bailout agreement following the 2008 economic crash, however according to a paper by MacCarthaigh and Hardiman[3] the Troika was invoked as an excuse by senior officials to push through reforms they themselves wanted. This over-reaching by senior officials is summed up by the authors who state “Once they could no longer shield difficult decisions from public criticism and political pushback by blaming them on the Troika, normal electoral considerations were likely to reassert themselves”.

The report of a study commissioned by trade union Fórsa last year also aligns with the above, stating that Irish local authorities perform fewer functions than municipalities across Europe, with their roles largely confined to physical infrastructure and environmental and recreational services[4].

With few formal functions and a weak financial base, local government in Ireland is particularly ineffectual[5]. Many of the services traditionally provided by Local Authorities, e.g. provision of social housing, bin collection, water services have been privatised over the past number of years at a considerable additional cost to the tax payer.

Local Authority Budgets

The Fórsa report referred to earlier also found that only 8 per cent of Irish public spending occurs at local government level, compared to an EU average of over 23 per cent, and that a quarter of the Irish spend is not fully under local authority control[6].

According to Reidy and Buckley “the narrow tax base and limited revenue powers meant that the impact of the [2008] economic crisis was rapid and severe at the local level and there was little capacity for local politicians to influence the incidence of the retrenchment”[7].

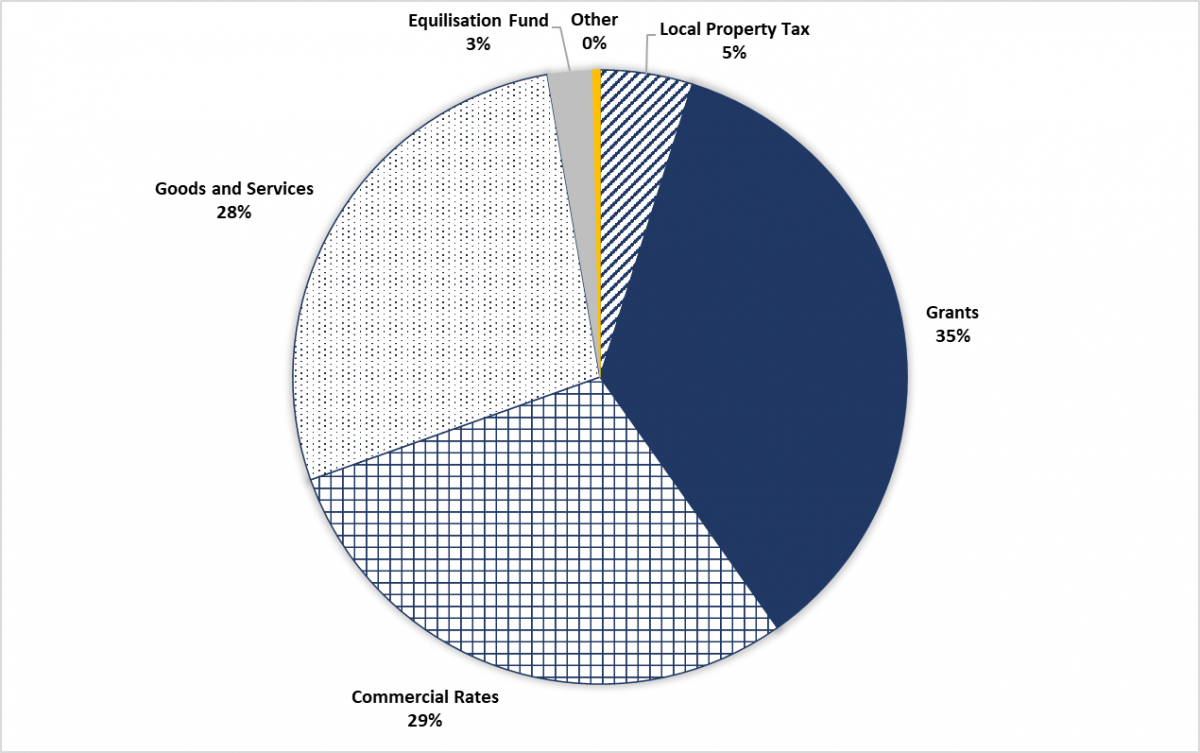

General Government Grants accounted for 35 per cent of Local Government income for 2020. Commercial Rates accounted for 29 per cent, and Local Property Taxes just 5 per cent (Chart 2). We are now facing another economic crisis. With over one-third of the Local Government Budget coming from Central Government, any constriction of General Government expenditure is likely to have a severe impact on Local Government capacity.

Chart 2: Local Government Income, 2020

Source: www.localauthorityfinances.com

Note: Other includes Provision for Credit Balance and Pension-Related Deduction

Participation

One positive impact of the Local Government Reform Act 2014 was the introduction of the Public Participation Networks (PPNs). The PPN recognises the contribution of volunteer-led organisations to local economic, social and environmental capital. It endeavours to facilitate input by these organisations into Local Government through a structure that ensures public participation and representation on decision-making committees within Local Government. Local Authorities and PPNs work together collaboratively to support communities and build the capacity of member organisations to engage meaningfully on issues that concern them. PPNs have a significant role in the development and education of their member groups, sharing information, promoting best practice and facilitating networking. Local Authorities also have a vital role to play in facilitating participation through open consultative processes and active engagement. Building real engagement at local level is a developmental process that requires intensive work and investment.

However, notwithstanding improvements in public participation, if Local Government so restricted as to be ineffective, participation at local level can only ever have limited impact.

Need for Reform

In their chapter on Government reforms, Reidy and Buckley had a prescient warning that, as the economy surfaced from the effects of the 2008 financial crash, “ the sustainability of these reforms will come into question as demands from various stakeholders increase, risking a return to short-termism in policy planning, inefficiencies in public expenditure and, ultimately, the undermining of public sector reforms”. Short-termism in respect of large-scale infrastructure projects such as the National Children’s Hospital, housing at O’Devaney Gardens, and the continued delay with the implementation of Sláintecare has seen costs rise exponentially from tender quotes and little in the way of policy planning.

An over-centralised Government creates a barrier to meaningful participation. While a significant amount of work is conducted by the PPNs, as evidenced by their Annual Reports, whether this work can deliver deliberative democracy is questionable in the context of a week and ineffectual Local Government.

[1] Reidy, T. and Buckley, F. (2017) 'Democratic revolution? Evaluating the political and administrative reform landscape after the economic crisis'. Administration, 65 (2):1-12. doi:10.1515/admin-2017-0012

[2]https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/studies/2015/self-rule-index-for-local-authorities-release-1-0

[3]https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/0952076718796548

[4]https://www.forsa.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MorePowerReport.pdf

[5] Reidy, T. and Buckley, F. (2017) 'Democratic revolution? Evaluating the political and administrative reform landscape after the economic crisis'. Administration, 65 (2):1-12. doi:10.1515/admin-2017-0012

[6]https://www.forsa.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MorePowerReport.pdf

[7] [sic]