Poverty rates for those living alone have risen in last decade

In the last decade, the poverty rates for single person households have risen notably, while they have fallen (or remained more-or-less static) for other household types. This is true for both people living alone and of working age, and for those over 65.

A notable demographic trend is that single person households are making up a greater proportion of all Irish households. This trend projected to continue. Lastest poverty figures from the CSO suggest that these single-person households may struggle more than others to achieve a minimum socially acceptable standard of living.

Last month the Central Statistics Office released the results of the Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) for 2018. The SILC gives us our official measurements of poverty and deprivation, as well as information on income, income inequality and much more besides. In our response to the SILC release, Social Justice Ireland noted that:

- 689,000 people in Ireland are living in poverty, of which 202,000 are children.

- 111,000 people living in poverty are in employment; the “working poor”.

- The number of over 65s in poverty has risen by 20,000 to around 78,000.

- Overall there are 36,000 more people living in poverty in Ireland today compared to 2008.

But these numbers alone do not give a comprehensive picture of the poverty situation in Ireland. In this article, we look behind the headline numbers, analysing poverty from the perspective of household composition. The SILC categorises households under the following headings:

- One adult, 65 or over, living alone.

- One adult of working age, living alone.

- Two-adult households where at least one is aged 65 years.

- Two adults, both of working age.

- Households containing three or more adults.

- Households with one adult, and with children under 18 years.

- Households with two adults, with 1-3 children under 18 years.

- Other household types with children under 18 years.

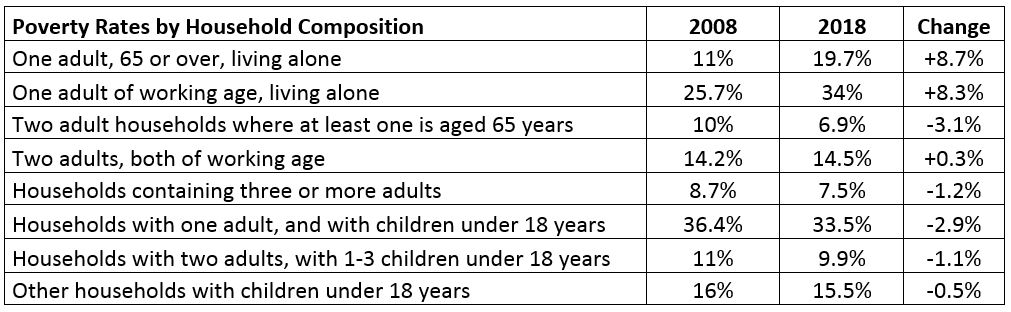

The table below highlights the respective poverty rates for different categories of household in 2018 (the latest year for which we have data) and in 2008, a decade previous. Among the interesting points immediately notable:

- The poverty rate for people aged 65 and over who are living alone has increased significantly over the 10 years measured. It is 8.7 percentage points higher than in 2008; an 80 per cent jump.

- One in three working-age adults living alone are living in poverty, up from one in four in 2008. This 8.3 percentage point jump is also significant.

- One in three households composed of one adult with children under 18 years are living in poverty, a slight decrease from a decade ago. These households are predominantly (but not exclusively) one-parent families; a group well known to experience a far greater instance of poverty than the general population.

Older people living alone in poverty

Since 2008 there has been a significant rise in the percentage of older people living alone that are living in poverty. It was 11 per cent in 2008, now it's 19.7 per cent.

A key factor in the poverty rates of the elderly is the level of the State Pension. In this context, it is worth noting that the 2008 rate above (11 per cent) is much lower than it was just a few years prior; in 2004, 37 per cent of this cohort was living in poverty. This fell dramatically in the following four years, mainly as a result of significant increases in the level of the State Pension between 2004 and 2008. Over those four years, the State Pension (Contributory) increased by a third, from €167 to €223.

This highlights very clearly the importance of the State Pension in the allieviation of poverty among older people. That there should have been an increase in poverty among this group from 2008 to 2018 should therefore not be surprising, given that the level of the the State Pension was frozen for eight years between 2008 and 2016.

However, a closer inspection tells us something even more interesting: the majority of that huge jump took place in just one year, from 2017 to 2018. While the at risk of poverty rate for those aged over 65 and living alone has fluctuated around an average of about 12 per cent in the last decade, it look a huge leap between 2017 and 2018, from 10 per cent to 19.7 per cent. Due to significant levels of wage growth, the official poverty line increased by over €1,200, from €12,521 in 2017 to €13,723 in 2018, an increase of almost 10 per cent. However, for households composed of one person living alone, median nominal equivalised income rose by just 4.6 per cent.

History has shown that at times of economic growth, if welfare rates do not keep pace with wage increases, poverty rates will rise. Universalising the State Pension and keeping it at a level sufficient to afford older people a decent standard of living will be key to reducing and eradicating poverty among our elderly. The Living Alone Allowance must also have a role to play in improving the situation for this group; we therefore welcome the increase in the Living Alone Allowance in Budget 2020 from €9 per week to €14 as an acknowledgement that those living alone face a different set of challenges than those living in households with many people and therefore more potential sources of income.

However, it is the level of the State Pension that has the most influence on the poverty rate for those over 65, and this seems to be especially so for those aged over 65 and living alone.

Working age individuals

The proportion of working-age people living alone who live in poverty increased by 8.3 percentage points between 2008 and 2018. This is an increase of one third on the previous rate.

What can the data tell us about these people? Well, while the SILC microdata for 2018 is not yet available, the 2017 microdata is instructive as it also shows 34 per cent of this cohort living in poverty and it's reasonable to assume that the make-up of this group will not have changed much in the intervening 12 months. Our analysis of the 2017 microdata noted the following breakdown of working-age adults living alone and experiencing poverty:

- a quarter are unemployed;

- 15 per cent are classed as "at work";

- 41 per cent belong to the category of "not at work due to an illness or disability".

It is clear from this 15 per cent number, as well as previous studies of the 'working poor' (those in poverty despite being in employment) by Social Justice Ireland, that the notion that a job is an automatic poverty-reliever is a false one. The job needs to be one with reasonable pay and decent conditions. It is likely that increased prevalence of precarious working arrangements and low pay are at least party responsible for the rise of poverty among this cohort.

However, it is also clear from our analysis that the main driver of these increased rates of poverty among working-age people living alone are those classified as "not at work due to illness or disability". In 2008, 51 per cent of working age people living alone and not at work due having an illness or a disability were classed as living in poverty. In 2017 (we don't yet have the figure for 2018 for this), this had risen to 76 per cent. This is concerning as these people are generally not in a position to take up employment (and indeed many may never be in such a position) and so they are greatly reliant on state supports.

We know from data already published for 2018 that, in general, people not at work becasue of illness or disability are more than three times as likely as the average person to be at risk of poverty. (They make up 12.3 per cent of those living at risk of poverty, despite making up only 3.8 per cent of the population). It is worrying that those living alone in this situation are at such a risk of poverty, as it raises questions about the robustness and viability of arrangements in place in Ireland to support independent living for people with disabilities.

If government is serious about assisting people with disabilities to live as independently as possible, it cannot continue to ignore the biggest issues facing them. Measures of relative poverty like those used in the SILC treat people with disabilities like the rest of the population and do not take into account that most of them have additional living costs as a result of their disability. This means that their actual situation may be much worse than the headline numbers suggest. For this reason, Social Justice Ireland has long advocated a Cost of Disability Allowance to acknowledge this additional cost, and to assist some of society's most vulnerable people to achieve a decent standard of living.

Conclusion

As noted above, in the last decade, the poverty rates for single person households have risen significantly, while they have fallen or remained more-or-less static for other household types. It should be acknowledged that the absolute number of people living in households made up of just one person (whether of working age or over 65) has increased greatly in the last decade. (It increased by around 50 per cent between 2008 and 2018). This is in line with a trend we've been aware of for some time: that single-person households are becoming a greater proportion of total Irish households. This trend is projected to increase in coming decades. These figures from the CSO suggest that Ireland might have a problem in ensuring that they can achieve a minimum socially accepted standard of living.

This is certainly in line with the findings of the Vincentian Partnership for Social Justice (VPSJ), who publish the MESL, or Minimum Essential Standard of Living. The MESL research identifies the cost of what is needed to enable a household to achieve a minimum acceptable standard of living below which society agrees nobody should be expected to live. The VPSJ has noted that while welfare rates for two-person households (where both are of working age) are not quite adequate, they do a better job of approaching adequacy (from an expenditure point of view) than for single-person households. This is in part due to the ability of households with more than one income to split certain costs, such as accommodation, home-heating, utilities etc.

More broadly, and relevant to the above noted finding that one in three households composed of one adult with children under 18 years are living in poverty, MESL analysis has also found that households headed by one adult demonstrate a greater rate of income inadequacy, and deeper inadequacy than two adult households. The VPSJ also noted in their submission for Budget 2020 that "deep income inadequacy is now exclusively found in households which are headed by one adult, i.e. single working-age adult and lone parent households, or in households with older children". This income inadequacy is now appearing in the SILC poverty numbers and presents a major policy challenge.

It should be noted that poverty rates are measured based on income, while the MESL is based on spending, i.e on the cost of achieving a minimum acceptable standard of living. However, while not directly comparable, the research again highlights the additional difficulties that people living alone face in achieving a decent standard of living.

If Government is serious about reducing poverty then policy must prioritise those at the bottom of the income distribution and it must be designed to address the wide variety of households and adults in poverty.

Social Justice Ireland has previously published 12 policy proposals for addressing income inequality and reducing poverty rates. Most relevant to the issues discussed are:

- Ensuring adequate adult welfare rates, and moving rates towards the Minimum Essential Standard of Living rates over a five-year period.

- Making personal tax credits refundable to tackle poverty among people with low-paid jobs.

- Supporting the widespread adoption of the Living Wage, so low-paid workers receive an income sufficient to afford a socially acceptable standard of living.

- Introducing a Cost of Disability payment, to ensure that the additional cost of having a disability is acknowledged and more appropriately addressed.

- Introduce a Universal State Pension to ensure all older people have sufficient income to live with dignity.